a collection of notes on areas of personal interest

- Introduction

- Arabic / Islamic design

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 01

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 02

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 03

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 04

- Islamic architecture

- Islamic urban design 01

- Islamic urban design 02

- Islamic urban design 03

- Islamic urban design 04

- Islamic urban design 05

- Arabic / Islamic gardens

- Gulf architecture 01

- Gulf architecture 02

- Gulf architecture 03

- Gulf architecture 04

- Gulf architecture 05

- Gulf architecture 06

- Gulf architecture 07

- Gulf architecture 08

- Infrastructure development

- The building industry

- Environmental control

- Perception

- The household on its lot

- A new approach – conceptual

- A new approach – principles

- A new approach – details

- Al Salata al jadida

- Public housing

- Expatriate housing study

- Apartment housing

- Pressures for change

- The State’s administration

- Society 01

- Society 02

- Society 03

- Society 04

- Society 05

- Society 06

- History of the peninsula

- Geography

- Planning 01

- Planning 02

- Population

- Traditional boats

- Boat types

- Old Qatar 01

- Old Qatar 02

- Security

- Protection

- Design brief

- Design elements

- Building regulations

- Glossary

- Glossary addendum

- References

- References addendum

- Links to other sites

Policing the peninsula

Although I have established this page with some of the headings that might be anticipated, such as ‘army’, ‘air force’ ‘navy’and ‘police’, the history of policing and Qatar’s Armed Forces in its wider sense is not so easily organised. Please also bear in mind that the initiative to begin this page was to establish a place for some of the photographs I have from the 1970s and 1980s and is not intended to be a history of this area of the society, important though it is.

In many respects Qatar feels, and is, a safe place in which to live. But there has always been a history of instability in the region and, in certain respects this state continues. It is not my intention to write in any detail about this subject, but it needs to be understood that the expansion of the State resulting from its wealth in natural resources, its increasing importance in both the region and world due to this and its physical location, and the massive influx of expatriates supplying its expansion have created the need to expand its internal and external security requirements and obligations dramatically. A very different state of affairs existed only a generation or two ago. In thinking about the structure and operation of policing in peninsula bear in mind that all areas are headed by members of the Royal family and their familial allies, an important and logical extension of the tribal systems of the region.

On other pages I have mentioned marine piracy and land-based raids as characteristics of social groupings in the peninsula, and mainly in the context of the resulting development of defensive architecture. At the same time those who lived on the peninsula sought a degree of protection both from within their own ranks or from external agencies. In fact this was often imposed on them, particularly from Ottoman and British initiatives which sought to safeguard the region to protect and promote their own interests.

The development of defensive architecture mentioned above has been looked at on other pages and can be characterised as structures built specifically as forts, fortified buildings, watch towers and domestic buildings. The first three categories reflect the need to guard against attacks mainly from outside the peninsula – either from the sea or land. Domestic buildings, while providing a degree of protection from the same perceived or actual dangers were not capable of safeguarding their inhabitants to the same extent; much of their notional protection was thought to give privacy as well as stopping thieves breaking in. The characteristic housing layouts gave a certain amount of protection with their high walls, narrow sikkak and the ability to spot strangers within them readily. This created a degree of security without the need for a formal policing system but, where there was trade, particularly storage, formal and informal policing was provided by watchmen and guards.

More to be written…

Guards and watchmen

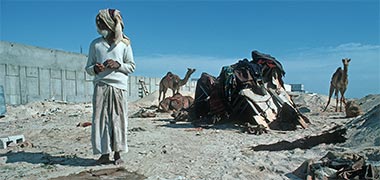

This photograph, together with that below are of watchmen, but with slightly different tasks. This is of a badawi employed by a member of the Royal family to provide a degree of security to the residential complex he was having constructed on the outskirts of Rayyan. In this case the badawi camped outside the surrounding wall of the development where his presence would have been sufficient to assure a degree of protection, not necessarily by his potential actions, but by association. In this case, it is the connection between tribes that is one of the significant and traditional factors in providing security and, in a more general sense, stability.

The second photograph was taken just outside Doha’s suq and is of a pair of badu employed to protect the suq, particularly at night. I believe they were guarding the whole of the suq rather than just a part of it, and that they were stationed in the Kuwt fort at the south end of the suq. There were also guards whose job it was to protect specific parts of the suq, usually those under the ownership of a single merchant or, perhaps, group of merchants. In those cases the guards would have lived in the owners’ properties and it is likely they would have had other duties and responsibilities during the daytime.

More to be written…

Police

The original policing of the peninsula might be thought to have been effected by the tribes themselves, or by foreign powers such as the Ottoman occupation or the British naval presence. Perhaps this should be considered to be a response to larger scale security. In many parts of the Arab world police forces were established with a degree of mobility suited to the area of operation and supplied with camels or horses. There were also foot patrols within urban areas but this responsibility was often taken on by guards or watchmen as described above.

The first formal police agency was established in 1949 with a presence in the centre of Doha. The Police Fort at Rumaillah was developed some time after the Second World War and housed both fledgling police and army units. With time both have developed into far larger organisations reflecting the need to deal with the large population as well as external pressures. As might be anticipated, there are well-trained cadres for dealing with a variety of areas including, but not limited to civil defence – which evolved from responsibility for fire services, vehicular traffic, airport control, drugs, criminal investigation and so on including liaison with the Interior Security Forces Department, known as lakhoya.

So, the police now deal with all those areas common to their counterparts in the West. But like much in this part of the world, there is not an exact match. While to some extent this is a reflection of the recommendations given by advisors brought into the country who advised successive Rulers as to their needs, those needs were a reflection of the concerns of the Rulers. It has to be anticipated that they were not exact parallels with those of Western countries as there was the religious and political character of the society to be considered. This has obviously been reflected in the detailed character, organisation and staffing of the police.

More to be written…

Army

Qatar’s army is very different now from what it was a generation ago. It has been heavily buttressed by Western forces resident on it and in neighbouring Bahrain, but it has also taken part in excursions abroad in line with its foreign policies relating to support of initiatives it and other agencies such as the Gulf Cooperation Council promote. In this respect it differs from other armies in the Arab world just as, for instance, European armies differ in their composition, numbers and concerns.

The main problem Qatar faces nowadays is in its lack of nationals to staff its military forces, particularly its army. Less than a third of the army is made up of nationals and, as might be anticipated, they tend to occupy the higher echelons, though this is not a rule. In the past expertise has been drafted in from neighbouring states with a militant history, though this has been a concern with the potential for conflicting loyalties. Sound training and the provision of good facilities and equipment have been thought to provide a partial solution to the perceived problem.

Information on Qatar’s army can be found elsewhere and it is not my intention to comment on it here. The notes on this page are concerned mainly with aspects relating to photographs I took in the 1970s. This photograph, for instance, is of two of the Ruler’s bodyguards. Dressed traditionally they are, nevertheless, soldiers but are carrying out the same duties as others would have performed for centuries with regard to protecting the head of their tribe or, for the last two hundred years, the head of the country. In a sense they are a more formal representation of those shown accompanying previous Rulers. Security for the Head of State and of many of those in charge of security

More to be written…

Navy

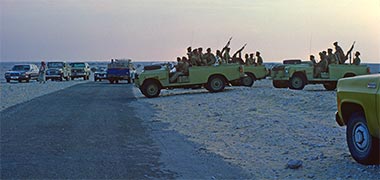

The Navy is focussed mainly on policing and defending its coastline. There has always been a concern for protecting the peninsula from piracy and sea-borne incursions. In the past the British took this concern seriously enough to patrol the Gulf in an attempt to prevent or at least limit the endemic piracy in both the Gulf and the Arabian Sea. Many of the Gulf states were able to raise considerable naval forces when required to do so, there being many different craft available to them due to the activities of pearling, fishing and trading between the Gulf and the coasts of Africa and the Indian sub-continent. The patrols which controlled the land border with Saudi Arabia and the littoral border continue, though now with different craft from that shown in these photographs, taken in 1972. Essentially these patrols attempted to control smuggling of people and goods, often from the other side of the Gulf, though also from along its south side.

Smuggling across the Gulf and into it continues to be a source of concern. To many it seems to be a natural way of life and reflects a long-standing tradition. Wooden craft still criss-cross the region, often using their sails to conserve fuel. Their cargoes are various and the traditions of evading or avoiding customs and revenue operations are ingrained. The navy is, therefore, equipped with fast craft and include a maritime interception group. While a small element of the overall Qatar Armed Forces, this is a popular area with the peninsula’s obvious strong links with the sea.

More to be written…

Air force

One of the recollections of the 1970s in Qatar was of Hawker Hunters flying low over Doha in the morning. My understanding was that they would make a sweep of the borders and marine approaches, then break for lunch. Whether this would have been enough to put off aggressors was difficult to say at the time. The Hunters had been given to Qatar by the British Air Force and this photograph, taken from a helicopter in March 1976, shows one of them in the process of taking off for its morning patrol. There were four of them though there was always a problem with spare parts and it was said that one of them was needed to supply the three others.

The Hawker Hunters of the Qatar Emiri Air Force have been replaced, mainly by French and American aircraft though there is still a British component of the Air Force. Originally all the pilots were expatriates with the obvious concern as to loyalties in case of conflict. This concern was similar to that felt with regard to the manning of the army, but in the case of the Air Force it seemed very different with the pilots being, in effect, the whole of this branch of the armed forces. Of course the aircraft were backed by an extensive ground crew but, again, there were few Qataris among them. Now, many Qataris have been trained to fly and support this branch of the military. Some have established world flying records and there is a continuing interest in flying, the Air Force being supported by other Western forces.

More to be written…

General

Elsewhere I have written about societies in the Gulf being typified by their internal relationships, as well as by their relationships with the expatriates in their various groupings and communities. Like many societies, the population is not a balanced one, in fact it is severely disbalanced in numerical favour of expatriates. While there are differences between Qataris based on their origins, there is a marked difference between Qataris and non-Qataris. This is reinforced by the legal definition required just to prove Qatari nationality – a distinction which is echoed around the Gulf – and where there is a pride in being Qatari with its strong identification with their country. Travelling around with Qataris, it is remarkable how noticeable expatriates are.

Traditionally Qataris have placed considerable value on the operation of the majlis system which governs behaviour, political allegiances, business and family life to a large extent. But this is being ameliorated if not broken down by a variety of pressures on Qataris as well as the ability to obtain and impart news instantly through their mobiles. It might be thought now more difficult to comprehend undercurrents in the society than it used to be, and the significant minority Qataris represent in population can only make this more difficult.

It must be anticipated that there is a significant interest in understanding these undercurrents and that the policing must cover this in a manner different from those in the West, organising its structures on the traditional ways of the society, but developing it to respond particularly to the massive influx of expatriates.

more to be written…

Society 04 | top | Society 06

Search the Islamic design study pages

- Introduction

- Arabic / Islamic design

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 01

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 02

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 03

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 04

- Islamic architecture

- Islamic urban design 01

- Islamic urban design 02

- Islamic urban design 03

- Islamic urban design 04

- Islamic urban design 05

- Arabic / Islamic gardens

- Gulf architecture 01

- Gulf architecture 02

- Gulf architecture 03

- Gulf architecture 04

- Gulf architecture 05

- Gulf architecture 06

- Gulf architecture 07

- Gulf architecture 08

- Infrastructure development

- The building industry

- Environmental control

- Perception

- The household on its lot

- A new approach – conceptual

- A new approach – principles

- A new approach – details

- Al Salata al jadida

- Public housing

- Expatriate housing study

- Apartment housing

- Pressures for change

- The State’s administration

- Society 01

- Society 02

- Society 03

- Society 04

- Society 05

- Society 06

- History of the peninsula

- Geography

- Planning 01

- Planning 02

- Population

- Traditional boats

- Boat types

- Old Qatar 01

- Old Qatar 02

- Security

- Protection

- Design brief

- Design elements

- Building regulations

- Glossary

- Glossary addendum

- References

- References addendum

- Links to other sites