a collection of notes on areas of personal interest

- Introduction

- Arabic / Islamic design

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 01

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 02

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 03

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 04

- Islamic architecture

- Islamic urban design 01

- Islamic urban design 02

- Islamic urban design 03

- Islamic urban design 04

- Islamic urban design 05

- Arabic / Islamic gardens

- Gulf architecture 01

- Gulf architecture 02

- Gulf architecture 03

- Gulf architecture 04

- Gulf architecture 05

- Gulf architecture 06

- Gulf architecture 07

- Gulf architecture 08

- Infrastructure development

- The building industry

- Environmental control

- Perception

- The household on its lot

- A new approach – conceptual

- A new approach – principles

- A new approach – details

- Al Salata al jadida

- Public housing

- Expatriate housing study

- Apartment housing

- Pressures for change

- The State’s administration

- Society 01

- Society 02

- Society 03

- Society 04

- Society 05

- Society 06

- History of the peninsula

- Geography

- Planning 01

- Planning 02

- Population

- Traditional boats

- Boat types

- Old Qatar 01

- Old Qatar 02

- Security

- Protection

- Design brief

- Design elements

- Building regulations

- Glossary

- Glossary addendum

- References

- References addendum

- Links to other sites

An approach to the protection of buildings

This page of notes is likely to repeat some of what was written on the preceding page that relates to security. Sorry about that. It was intended that the previous page should deal mainly with aspects of security relating to residential buildings in Qatar, while this page would be more general in its outline and potential application. This page also deals with security relating to buildings, but more from the perspective of protection. So there may be repetition as I have mentioned, but it is possible there also may be contradictions. Bear in mind that these are only notes. I have yet to reconcile, correct and structure many aspects of what I have written.

We must accept that the character of our cities has changed. No longer is there the freedom to move at will, neither in the private sectors, nor in the public areas. Whether the impetus for attacks is economic, political or eccentric, design in the public realm now must take account of the need for increased security. One of the outcomes of this, and which is looked at on the urban design pages, is that we are increasingly kept out of buildings or away from their peripheries unless we can demonstrate we have business there. This is an important factor not only in our urban design strategies, but one that also has socio-political repercussions caused by the growing cadre of security personnel and systems policing our movements.

It seems appropriate to comment here briefly on the rationale for protecting buildings with its implication that it is the people in and around them who are being protected. Collectively we appear to be at ease when we believe we are in control of our own protection – for instance when driving a car, despite the fact that thousands are killed every month in motoring accidents – yet we take extraordinary measures when we feel we have no control – for instance in flying, when relatively few people are killed compared with motoring or, indeed, many other areas of risk.

So, in a similar way to which the Health and Safety industry has burgeoned, there is now a significant industry geared to protecting buildings and those who use them. That is not to say that this is unnecessary, but similar thinking appears to govern areas of potential danger. There are real risks to our freedoms. Media reports and political initiatives should not increase our anxieties and trigger increasingly restrictive measures. Respect has to be maintained for those applying new measures, their actions not affecting our confidence or creating mistrust by abusing their authority.

We need to have a better understanding of degrees of risk in order to ensure that not only are buildings, their occupants and the public sensibly safeguarded, but that designers, owners and managers understand, design and operate for those levels of risk and are appropriately covered by insurances – bearing in mind its unpredictable nature.

The security that is provided for us attempts to guard against the most recent character of attack. But this is theatre and ignores the broad threats. Those who intend to attack us will attempt to circumvent the measures taken to safeguard the public. The only way around the problem is effective intelligence, investigation and emergency response. Much of what drives protection is based on terrorism. Remember that the whole purpose of terrorism is to terrorise: it is not so much the act, but our reactions to the threat of it.

Public and professional responsibilities

Security is a discipline increasingly affecting all who move in and about the public domain. We are perceived to be at risk from attacks which are not fully defined, either in terms of attacker or character of attack. Nevertheless we understand there is risk. In our public capacities we are required to be vigilant, though this is widely misunderstood and, in a professional capacity, designers are increasingly required to take the possibility of attack into their considerations. This is difficult for them. They may be found legally liable should they fail in their designs to provide reasonable security and safety in the event of an attack which they can only imagine.

But it is difficult for designers to envisage what their designs must reflect in terms of security. It may be thought that the client of a project should be required to define the perceived risk in some detail, and the professionals design for that or those risks. However, buildings change hands, time progresses and, while history may provide certain lessons, those who attack buildings are free to invent novel approaches to circumvent the obstacles they see to achieving their objectives. Legal precedents in the West demonstrate that, where attacks are successful, professionals may be called to account for perceived failures in their designs.

The hardening of buildings and areas against attack has a displacement effect. Those who seek to attack what are perceived to be strengthened targets just move on to softer ones – unless there is a specific reason for their targeting a specific building. Usually, however, these buildings will be understood to be at risk and counter-measures will be adopted into their design or into their operation.

Because of increased risk, a number of approaches have begun which suggest methods of assessing risk in order to produce designs that are robust and sensible, giving clients a certain degree of reassurance and, by extension, providing safer environments for the public and those moving in and around these projects. Perhaps, in a negative sense, this also provides the designers with some degree of reassurance against the possibility of future legal actions.

Finally, I should repeat something I’m sure I will have mentioned elsewhere. If I haven’t, do bear this in mind: despite the focus of these notes, a degree of common sense must be observed. The majority of buildings will not be attacked; ownership and tenancy of buildings changes with time; disaffected groups come and go and it is expensive to provide fail-safe protection to all buildings. Discuss issues with your clients and make a note of the decisions taken but, where practicable, lean towards solutions that may protect those moving in and around buildings.

Analysis

The most common approach is a form of analysis usually known by the mnemonic. PEST or PESTLE, which requires the issues relating to potential attack being analysed under the headings:

- Political,

- Economic,

- Social,

- Technical,

- Environmental, and

- Legal.

This has recently been extended and rearranged to become STEEPLED by the inclusion of:

- Ethics or Education, and

- Demographics,

though these latter two areas may not be useful here, but subsumed within the foregoing.

The purpose of this analysis is to identify objectives that should be pursued in order to create a perceived level of security. The original PEST was a concept developed for the business world. Nowadays there are many disciplines that use this form of analysis but, from the point of view of security the issues might include, but not be limited to, consideration of the following in general terms:

Political

Political factors in the case of security will include such issues as the displacement of attacks from hardened projects to softer targets. It is logical that anybody wishing to attack a target will look for a low or at least only optimally secured target. The more security is improved on projects, the more likely attackers will look elsewhere. An associated issue is what is known as the ratcheting effect which sees incremental improvements to projects driving up the degree of security on subsequent projects – including, with time, the security of the first project.

At a macro level, decisions are made on our behalf which affect the direction and financing of strategic policies. Generally this affects us in the public realm, though we are not always aware of it other than in our observation of surveillance cameras and the presence of police. At a micro level, clients and their designers have to make decisions on the weighting to give different areas and aspects of security for their projects, both in terms of initial design and build as well as in the day-to-day running of their projects. Every decision has a consequence in both positive and negative terms, and a reasonable balance must be found to protect those using buildings as well as those moving around them.

Economic

Political decisions have economic consequences which must be funded through the tax system. The cost of improving security has to to be weighted and balanced against all the other budget heads competing for funding. At its simplest, either more funding has to be found from taxes or other budget heads have to be reduced.

With improvements in the security of projects comes, usually, increases in project cost. This applies not only to the initial design and construction phases, but also to the running costs. If the security system depends on anything other than passive systems, there is almost always a cost in providing personnel and maintaining the system or systems. These costs are short and long term and have to be borne by the clients who will, of course, recoup them in one way or another. But it is also worth remembering that the cost of designing and constructing a project is usually far less than the cost of running it.

Social

Society has a general awareness of the risks posed by the possibility of their being attacked. But in an open society there is often resistance to the imposition of restrictions, particularly when they appear to be poorly considered, badly formulated and inexpertly applied as is now happening in many Western countries. This also has political ramifications. It is imperative that where there is a need to impose restrictions, there is a balance sought and understood in terms of the constraints on personal liberties. This requires debate, understanding and consensus, but there is an increasing tendency in governments to collect information because it is easy and they are able to, but often without the attendant capabilities for safeguarding, rationalising, scrutinising and producing usable information.

This debate affects all of us but in differing degrees depending on a wide range of social and cultural characteristics. Cultural aspects will differ throughout the world but issues will include attitudes related to age, health, relationships, career aspects, mobility, risk and safety.

The point of this is that increasingly restrictions are sought and imposed on the users of buildings. Designers need to be aware of the solutions they find to perceived problems in order to minimise the effect of those solutions on those moving in and around their buildings.

As a corollary to this it is notable that there is increasing evidence of those with legal authority – and even those without – taking actions that are illegal or inappropriate, issues that give rise to a variety of reactions ranging from annoyance to lack of trust, both having serious ramifications for democracy and the respect of the law.

Technical

As time progresses our understanding of, and capability to use materials and techniques effectively moves forward. Technical and technological advances are rapid and can be adopted by those providing security to harden targets, though there is a tendency to delay due to the need to seek and obtain agreement for funding related to project costs. But by the same token, those contemplating attacks have a wider palette of choice available to them and are not necessarily constrained by normal funding procedures.

A second consideration is that as more targets are hardened, the more likely attackers will formulate strategies to overcome the defences or, as mentioned in the political issues, move to softer targets. This applies at both the macro and micro levels.

In terms of the way in which buildings work, technical improvements are likely to be introduced over the lifetime of all buildings, and users will have to adapt to the changes.

Legal

Attacks on buildings are, obviously, illegal. Counter-terrorism agencies will do the best they can to anticipate and oppose attacks, but they are rarely legally assailable for perceived failure, other than in a political sense. However, designers may be. Most designers are now required to obtain and hold cover – known as Professional Indemnity Insurance – which is intended to provide a measure of reassurance both to them and clients in the event that their designs are found wanting. So, increasingly designers are being required not just to provide buildings which stand up, resist the weather and function reasonably, they are also being required to consider potential attacks. This is not necessarily a requirement but common sense, both from the clients’ and professionals’ perspectives in order to reduce the risk of legal action being taken against them at some undefined point in the future.

Regulations differ around the world but, for instance, under the Health and Safety legislation in the United Kingdom, owners or occupiers of buildings have a duty of care to their employees and others moving in and around their buildings. Should there be an incident affecting the health or safety of these people, there is likely to be an investigation to ensure both that relevant legislation was followed, and that reasonable care was taken to protect and safeguard them. In an increasingly litigious environment owners and occupiers must consider their legal positions as early as possible.

There are areas where designs intended to resist attack produce conflict with existing legislation as well as common sense. Designing for the disabled, for instance, is an increasing requirement of designers, legislation requiring that the disabled are not treated differently from those with no disability. The most likely area for conflict with legislation is access to buildings where some of the techniques for resisting attacks will create difficulties for certain disabilities. What has not yet been understood by designers is the wide range of disabilities commonly found, and how these need to be provided for generally as well as in hardened buildings. The point of this is that there are increasing numbers of individuals and organisations seeking access to the courts in order to obtain redress under existing legislation. This may increase with certain detailing introduced to resist attacks on buildings.

There is also a legal issue relating to the access to, and use of, information. Put another way, those with an interest in obtaining information to help them resist attacks on buildings may be indistinguishable from those with an interest in researching and designing an attack on buildings. More than this, there is potential conflict between those engaged in legal and acceptable activities, and those who may be thought to use those same activities for illegal purposes. The photographing of buildings is such an activity, one which is increasingly considered suspect and where those attempting to restrict its practice are often poorly briefed. See the social area above.

Environmental

Environmental and ecological issues are increasingly considered and incorporated into buildings designs. Designs are now having to reflect our concerns for protecting, or not harming, the environment, particularly with regard to a project’s carbon footprint. This is considered to include the whole of the life cycle of a project, from its inception through construction and use, to its being recycled at some stage in the future.

This concern affects the manner in which a project is placed in relation to the ground, the way in which it is planned, designed, constructed and maintained, and both the selection of materials as well as the way in a which a project is detailed with regard to environmental concerns – at its simplest, the manner in which buildings are warmed, cooled and ventilated.

There are many areas in which environmental concerns are likely to conflict with security requirements. For instance, ventilation is an obvious concern as that suggests unobstructed openings in a building’s façade with the risk of gaseous material ingress; and lightweight façades conflict with the mass required to resist blast.

With the objectives identified from a PESTLE analysis it is common to move to another form of analysis known by the mnemonic, SWOT:

- Strengths,

- Weaknesses,

- Opportunities, and

- Threats,

which, as can be readily seen, seeks to identify the positive and negative characteristics of the objectives selected for development in the PESTLE analysis. Like PESTLE, it is a common form of business tool, both analyses designed to focus on the issues relevant to the problem of, in this case, secure design, and to identify the optimal strategies to follow. Their benefit is in forcing clients and designers to focus on the issues relating to security, and to develop agreed strategies to meet the objectives they have defined.

Professional responsibility

The foregoing areas of PESTLE analysis are general in this description. However, it is possible to develop more detailed analyses depending on the character of project and the degree of involvement of the designer. The main point to bear in mind is the increased responsibility designers have for their work in the area of security. It is sensible to document the approach carefully, establishing the parameters for design and confirming them with the client.

The character of the threat

While the notes I wrote on the previous page relate more to personal attacks, with the implication of the threat being attack or intrusion with or without small arms, these notes relate to the safety and security of buildings where the threat is more likely to be explosions.

Qatar suffered a single bombing attack in 2005 when one man was killed and a dozen injured. While this was not seen as the beginning of a campaign of violence, it was unusual in a country where there is a significant intelligence and policing system in place, and where it feels safe to live. Since then there have been no more bombings. Of course there have also been bombing attacks in Europe, Africa, north America and the Indian sub-continent. Bearing in mind the complex pressures operating within the region, it follows that a heightened awareness of the possibility of future bombings is necessary. Bombs appear to be the preferred method of attack of terrorists today, given the relative ease with which they can be designed, sourced and delivered. It follows that consideration of this character of attack is necessary in the design and development of buildings, as well as in their operation.

Delivery

Although I have suggested that explosive devices are the main concern for designers, biological, chemical and radio-active substances are also possibilities to bear in mind, though little might be done by designers to prevent or slow their dispersion. This is really the area for counter-terrorism agencies. So, to start with, the methods by which the more common, explosive devices are usually delivered should be considered. At its most simplistic, the basic delivery may be made:

- unwittingly, or

- knowingly,

the former, commonly the result of hiding a device on a vehicle that is allowed to enter a targeted building or area; the latter carried on a

- person, or a

- vehicle – air, water or, most usually, land based,

which can be made more difficult for the building designer by the possibility of delivery by:

- more than one person or vehicle, or by a

- combination of people and vehicles.

These possibilities can be further complicated by their delivery being made:

- at the same time, or

- phased over time,

the latter a strategy commonly designed to maximise casualties.

But these are not the only way in which delivery can be made. In addition to the above there is the possibility of

- delivery by a projectile, or

- hiding a device or devices at a time when access to a building is not restricted.

The former method can be countered to some extent by consideration of the possible means available to an attacker. This will be dealt with later but there will need to be consideration of delivery methods either with or without line of sight.

Hiding a device is not one that can be easily dealt with by a designer as it is essentially an internal security issue. It underlines the need to maintain vigilance of works carried out on buildings, not only in their construction, but also on works of maintenance as successful attacks have previously been carried out this way.

Finally there is the possibility of delivery through any system that enters the building. This will not be spelled out here but would include utility and mail delivery systems.

Targets

Whatever the purpose is for using explosive devices, they are generally operated against targets with no concern for life and limb, it being generally intended to maximise death and injury. Though this may be seen to be their main purpose, bombings are intended to fulfil a number of objectives – in no particular order:

- advertise a message, usually political,

- create a climate of fear,

- cause economic damage,

- destroy facilities, and

- tie up resources

for, in this way of thinking, people are considered to be dispensable and looked upon as collateral damage. However, some attacks are specifically aimed at individuals, groups or organisations, and may be vindictive, related to criminal activities, or have the intent of reducing the capability to respond.

Bombs are such an extreme form of attack that their use can often strengthen the will to resist and, in this regard, can be thought a self-defeating strategy. Regrettably, history has shown that, under certain conditions, the psychological pressures their deployment introduces can have a part in changing the will of organisations and governments.

Targets are generally selected for their strategic, operational or symbolic value and this draws together a wide variety and character of operations. These include, but are not limited to:

- communication systems and nodes,

- utility production, storage and distribution,

- government organisations,

- law enforcement,

- the military, and

- symbolic structures and organisations,

to which should be added targets which appear random but might be the result of irrational beliefs or criminal activities:

- retail activities and their outlets,

- educational and research establishments,

- staff of the above,

- individuals against whom there may be a grudge held,

- politicians, and

- criminals.

This may seem a long list, and examples can be readily found to support each of them, however the first grouping is the more likely set of targets.

The purpose of spelling these out is that designers must have not only some understanding of the tenants of their clients’ buildings, but of potential neighbours. While their building may not be a target, a neighbour might. In addition, a change in tenancy could introduce risk. Because of this it is wise for a designer to discuss with, and obtain direction from, the client in order that both are aware of the possibilities for attack, the designer is able to give advice and, where instructed, incorporate safeguards into the project. But, more than this, it is sensible to make provision for certain safeguards regardless of instruction. As was mentioned further up the page, following a dramatic failure, it is increasingly common for owners and authorities to cast about for people to blame in order to hold liable and, perhaps, obtain funds to assist in reconstruction.

Building location

The location of a building is rarely within the overall control of a designer, unless a large complex of buildings is being considered. But in such a complex it is obvious that some buildings may be more easily located with regard to security than others, though choice may be limited.

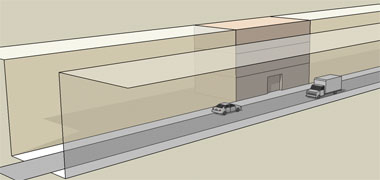

This diagram represents the most common siting of commercial buildings, illustrating the notional positioning of a building on a normal street. The building is placed with its façade on its boundary in order to maximise use of the site, and a road runs in front of it with a pavement each side of the road. Its major risk arises from its exposed faces: those at the front and back, as well as its roof. The character of security protection will differ on all these three sides of the building. It is also worth noting that the sides of properties – the party walls – may also be at risk, a characteristic which is taken into consideration with banks and similarly institutions, though mainly from the point of view of preventing access rather than resisting an explosion or projectile.

In a mid-terrace position the building is at risk from direct and indirect missile attack, illustrated by this first diagram. It is significantly at risk from directly across the street where there seems to be an implicit understanding that there will be some form of security within that building to prevent such an attack, though there is unlikely to be a practical way in which this can be safeguarded. As mentioned further up the page, although a significant responsibility lies in the hands of the security authorities, decisions need to be taken by clients and their designers as to what can be sensibly protected, and what can’t. Such a property is also at risk from the positioning of explosive devices either outside, or driven at the building as is illustrated by the lower diagram with a car and lorry. But devices have been moved against buildings in buses, tankers, vans, motorbikes, bicycles and pedestrians. Generally it is protection against blast and fire that must be considered, which suggests that it is the façade of the building which is at most risk including, particularly, its entrance.

Tight urban situations such as this suggest that protection needs to be directed to preventing access and limiting damage caused by an explosive device.

Increasingly buildings in Qatar are being located as discrete structures. In order to take advantage of their expensive sites they tend to have relatively small footprints, are tall and contain a large working population, a characteristic that brings problems with regard to moving that population into and out of the building within a reasonable time. This is a problem that will be looked at later. Surrounded by hard and soft landscaping these structures give clients the opportunity to have their building seen in the round, a possibility that leads to their being expressed as architectural icons, a practice which, in the New District of Doha, is producing design conflict. But that is another issue dealt with on the urban design pages. The issue here is that iconic buildings, by their nature, can attract unwarranted attention by virtue of their representing the individual, corporation or organisation that owns or inhabits them. This suggests an added source of risk in terms of projectile attack and, theoretically, increasing explosive risk due to there being access to more of its perimeter for pedestrians and vehicles.

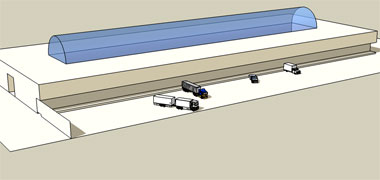

A third form of building development in Qatar is the shopping mall. The type is characterised in being enclosed, containing wide pedestrian thoroughfares giving access to a variety of, generally, up-market retail outlets. Some of the malls are single level but a number have more than that with access between levels being obtained by inclined travelators or moving pavements. The smaller malls have access from adjacent car parks, the larger ones from parking structures below them.

Goods are delivered to the shopping units from within separate service areas permitting vehicular access to the rear of the units or, in the larger malls, from below. This illustration shows a single yard allowing lorries to back onto loading bays raised to the level of their beds. Access to the malls for the public is from a separate access usually at grade as shown here on the left of the structure, or from a parking area below the mall as is shown in the photograph below. Bear in mind that retail systems depend on encouraging potential clients to move easily into and around their buildings in order to make money, and single level systems are generally preferred. Put another way, if there has to be more than a single level – including parking – there must be an easy way of moving between levels. Bear in mind that both men and women wear clothes that reach to the ground and there are safety issues relating to steps.

As mentioned in the preceding paragraph, this is a parking structure in a large mall development in the New District of Doha. Note that the height of this parking area is unusually high for a parking structure, probably because of the need to bring in tall trucks for servicing the retail areas above. This height also helps in providing a more comfortable feeling for many of the people using the system, there being a psychological concern for low ceilings in the area. The ability to introduce explosive materials underneath a structure should be avoided if at all possible.

Malls are areas not only for retail purchase but also provide a form of passive recreation. In this they replicate the traditional aswaaq though with a higher number of visitors, particularly expatriate. As building forms they can be thought of as closed systems with limited vehicular access, though with extensive delivery access. Vehicles have to be able to access at least the service area and, in certain cases, the pedestrian areas for maintenance, cleaning and fire-fighting.

Access to buildings

On the urban design pages i have written about some of the issues concerning access to buildings from the public point of view. Slowly, the public is becoming aware of some of the issues relating to security, the main drivers of this being the restrictions relating to photography and access near military and security installations, and the monitoring of access to office and public buildings as well as to corporate buildings.

From a socio-cultural point of view this is not a welcome innovation as it conflicts with the traditions of hospitality and the manner in which the peninsula’s population have traditionally discovered and disseminated information. Restrictions on movement are unpopular, more so if these restrictions are applied by expatriates which, in the main, they are or are seen to be.

Due to a number of factors there has been a tradition for expatriates to spend most of their leisure time in passive activities. This means that, out of normal work hours there are a considerable number of people circulating in public spaces, particularly where there are recreational and retail activities. But, through the day there are also significant numbers of people moving around the main urban centres, so much so that there are traffic problems on the roads and in parking areas. A lot of this traffic is associated with the construction industry, an activity that brings with it a number of problems particularly associated with that character of traffic.

In a general sense there are a variety of considerations that may be used to prevent vehicles getting close to buildings. The chief difficulty designers have is that there are a variety of vehicles that can be understood to require access to or near buildings, and consideration has to be given in balancing the conflicting requirements of statutory access and security. The most obvious vehicles that need to get close to buildings are emergency vehicles:

- fire fighting appliances,

- security authority – including armoured vehicles,

- supply and delivery,

- mail,

- maintenance,

- landscaping,

- refuse,

- utility vehicles and

- ambulances,

though it might be thought ambulances may not need close access, but use folding stretchers to move people from a building. It is the fire fighting vehicles that definitely need to get close to the building, local codes requiring and governing the distances required for both turntable and ladder access as well as hose-delivered liquids and foams, usually water.

Most of the other categories of vehicle might be kept at a distance from buildings, but there is always a case to be made for large, heavy, awkward or unpleasant loads to have their transport distance between vehicle and building minimised. The manoeuvring of coffins are often forgotten, for instance.

The other category of vehicle that needs to have access to buildings is that for the

- disabled,

a category that requires not only getting near to the building but also covers entry into and movement within buildings. There is also an argument or a requirement that some forms of disability require a vehicle moving close to a building and then allowing a person with limited mobility or a vehicular chair, to move into the building. This is governed by regulations that differ from country to country, but the trend is driven by legislation that requires everybody to be treated the same or, more accurately, that nobody should be discriminated against.

In addition to the list of vehicles requiring access to a building, I should have mentioned earlier, two obvious categories:

- guests and visitors brought by taxi, and

- VIPs brought by limousine.

both categories of whom traditionally enjoy the right to be brought to the main entrance, usually under the protection of a canopy to prevent their being rained on. This relates to issues that are

- cultural, and

- environmental,

factors that govern the relationship between vehicles and entrances. The socio-cultural practices of the region require guests to be able to approach the main entrance of a building. By extension many people believe they have the right to move right up to a main entrance either driving themselves or, more commonly, being driven by a chauffeur or driver. This factor is reinforced, particularly during the hot part of the year, by the fact that air temperatures are debilitating during at least daylight hours, and the need to move rapidly from an air-conditioned vehicle through this heat and humidity to an air-conditioned building interior is imperative.

The purpose in spelling out these issues is that there is virtually always a need to be able to take vehicles both to the

- front entrance of a building, as well as

- around it for fire-fighting purposes.

Because of this, the need for identifying and filtering vehicles approaching buildings is increasingly important, as is the ability to incorporate systems that will prevent unwarranted access to or near buildings for those considered to have no business being there. This usually has to be effected by a combination of methods which depend on mechanical and electronic systems supervised and directed by security personnel. For some categories of people this will be assisted by the police who will have full control of the road system, but individual buildings and groups of buildings are likely to require their own discrete systems to deal with the problems.

more to be written…

Barriers

The first principle of protection is to exclude as many types of vehicles as possible from the immediate vicinity of buildings. However, as mentioned above, there will always be a number that have the right to approach on a regular or specified basis, and there will be a need to filter these through. In order to prevent other vehicles approaching buildings, a variety of barrier systems may be deployed.

In a conceptual sense barriers can be thought to:

- prevent movement towards a protected target, or

- shield a target against blast or, of course,

- preferably both,

and should include monitoring systems that are able to identify and, if necessary, divert traffic away from buildings.

Whichever of these concepts are selected, it is important that consideration is given to protecting people against blast from wherever a vehicle is stopped or brought to a halt, though this is not easy to organise in practice. The tendency to use massive bombs suggests that many of the monitoring points are likely to be sacrificial, along with their personnel. So far it has not become possible to have unmanned monitoring points that will deal with all contingencies. This suggests that careful signing and hierarchical monitoring should be considered where possible.

As events have shown over the last few decades, some of the attacks against buildings use such massive amounts of explosives that buildings will suffer extensive damage – and there are likely to be considerable casualties – even when the source of blast is some way away from the targeted building. Regrettably this means that the position where a vehicle is brought to rest, and from which the blast will originate, is nearly always close to a security point by virtue of the manner in which these systems are designed. As these are generally manned it means that the security point and its personnel are almost guaranteed to become part of the collateral damage.

This points to an obvious solution whereby control is maintained electronically, and from a distance. The reason why this is not put into practice is because of the need to inspect vehicles closely, a process that is not capable of being carried out electronically – yet.

Preventing vehicles moving towards a target is usually accomplished by

- physical barriers,

- substantial changes in level, or

- constricting width,

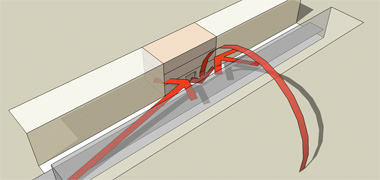

though what may be suitable to prevent a lorry or car moving forwards may be no obstacle for, say, a motorbike or bicycle – or, of course, a pedestrian. It follows that as many types of vehicle as possible should be excluded from the immediate vicinity of a building, and kept as far away as is practicable. In order to accomplish this it is useful to consider the roads, parking and service areas as a single system constrained at its sides by barriers which do not permit access over them. This notional diagram illustrates the principle – including a security point with adjacent rising blockers – though does not take account of service access, other than to the front of the building.

The pedestrian system should be kept discrete from that used by wheeled transport both in order to improve security as well as to allow pedestrians a degree of safety. Within pedestrian areas provision should be made to prevent vehicles moving across them towards adjacent buildings. At their crudest barriers are often seen as solid walls, perhaps formed of decorated pre-cast concrete panels, such as those found around the Senior Staff housing on the New District of Doha, and sometimes as steel fences or bollards.

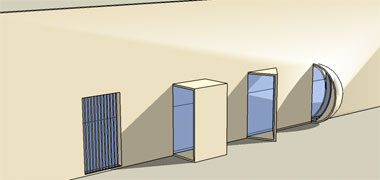

This graphic is intended to show a selection of ways in which a degree of security may be provided on a pedestrian concourse for adjacent buildings. It illustrates a variety of units which might be used to prevent vehicles running at a building. Apart from the wall and the ditch and continuous seating systems, it is unlikely that there would be significant protection against blast should a vehicle be driven at them.

It is assumed that the direction of attack is from bottom right to top left. From left to right on the back row there is a

- steel fence designed to allow a degree of transparency,

- a low hedge with a steel fence set in its centre,

- trees located in a ditch,

- pre-cast concrete blocks at sitting height, and a

- raised water feature similar to this sketch;

On the front row, again from the left, there is a

- plain concrete wall,

- a water feature with straight sides,

- a ditch with sloped sides and a continuous seating feature,

- a row of stone or concrete decorative spheres, and a

- raised concrete flower bed.

This is not intended to be exhaustive but only to illustrate how the principles might be turned into a design vocabulary. A good landscape designer will be able to produce a series of features which will achieve the security objectives required of the project.

Steps and ramps

What is not illustrated here, and an area which causes design problems from the point of view of security, is the need to produce ramps wherever steps are used in the designs. Steps can be driven up relatively easily by most vehicles but have to be provided where pedestrian access is required at a change of level. Where steps are provided, most countries require ramps to accompany them, ramps being easier to move over than steps. There are four principles that might be considered in order to safeguard the provision of steps and ramps from a security point of view:

- ensure that the use of steps and ramps does not allow vehicles to move onto a pedestrian area unless there is a secondary line of defence in front of the building,

- if steps and ramps must be provided, ensure that they are too narrow to permit four wheeled vehicles to move up them by the provision of a substantial handrail system, and

- where ramps are provided, use sharp turns to prevent four-wheeled vehicles moving up them, and

- in all cases ensure that the steps and ramps do not permit vehicles to have a direct run at an entrance.

Note that it is virtually impossible to prevent two-wheeled vehicles moving up or down steps, and not all that easy to prevent them manoeuvring over barriers. Only high wall systems will prevent this. Where steps have to be designed to prevent four-wheeled vehicle access then substantial devices have to be provided which act as barriers in themselves and do not permit vehicles to move between them. This is not an easy problem to resolve and can look crude as some of these sketches illustrate.

Road barriers

In 1985 there was an attempt on the life of the Ruler of Kuwait by a suicide car bomber. This single event immediately saw a number of Gulf states incorporating – what were known as vehicle barriers in Qatar – pre-cast concrete kerbs, substantial and high enough to prevent vehicles driving over them, along the major roads. Here to the right you can have an idea of their character from this view from a car. This kerbing is not as attractive as it might be, the quality of casting and installation having some effect on their appearance, with some being painted.

Individually vehicle barrier units are heavy enough to resist a vehicle driving directly at them – provided that they are set properly in a concrete base and buttressed behind effectively. This particular unit is being used in a temporary parking control system, a fairly typical scene around the country. This view is of its back face, most of which will be hidden when used in conjunction with a raised landscaping bed as is shown in the lower illustration. The yellow paint is being used solely to help make the unit more visible in its temporary use.

Here you see the preferred manner in which vehicle barrier systems are installed in Qatar. The road to the right is trimmed with a standard, small kerb, the back of which is paved. The purpose of this trim is not to act as a pedestrian path – it is too narrow for this – but to improve the appearance of the junction of road to barrier as well as forming a more substantial trim on its front face than might be provided by the road’s softer tarmac. In this example, the top line of the kerb is visually softened by the low, floral planting.

This shows the narrowest vehicle barrier installation that has been introduced in Qatar. The Rayyan Road is a relatively narrow road. It always has been though it is in the process of being widened where possible. As a dual-two there is little room for a median with planting on it so a double-sided median barrier unit has been provided, each side of it flanked by a narrow paved kerb.

But not all vehicle barriers are as well integrated into the road design, nor are they unnoticed. Here, for example, is a detail of a run of barriers loose-laid beside a road, probably as a temporary measure to protect works beyond them. They are clearly noticeable by their being painted yellow and black stripes, a pattern which is universally recognised as requiring attention to be paid to them. These barriers are often used in Qatar where there is the need to provide a degree of protection, or even security. These appear to be a temporary measure and have been provided with holes to facilitate lifting and moving. An increasingly common barrier is now appearing. Constructed of plastic and hollow, they are filled with water to provide mass and are readily emptied and moved without heavy equipment. Whether or not they are as secure as concrete units such as these, is debatable.

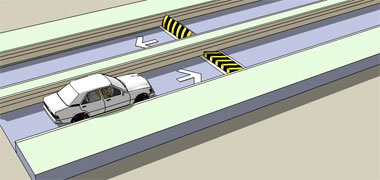

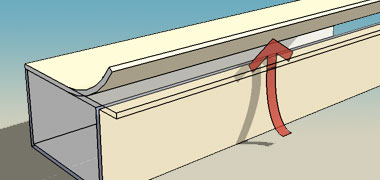

This illustration shows the principle of constraining roads at their sides with a road or kerb blocker situated to impede progress. The blockers are contained within a trench in the road, their normal position being raised. When a vehicle approaches they drop to allow the vehicle to move over them, the signal being given either from a security point or from a signal made from the approaching vehicle, the former being preferable for obvious reasons. Note that the blockers face the same way in order to prevent vehicles attacking against traffic flow. Sometimes designers forget that attacks do not follow traffic rules… Also note that a number of organisations such as petrol stations and supermarkets are using a form of barrier which shreds tyres when vehicles move over them against traffic flow. These are useless in preventing vehicles moving forward as most will be able to drive on wheel rims.

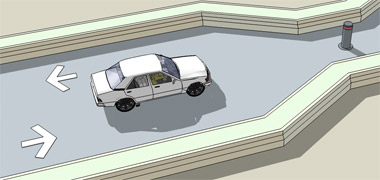

This form of blocker is also being used more often. It consists of a vertical cylinder that is normally in the raised position, blocking traffic, but can be lowered by a variety of systems. These can be operated by a driver, proximity, or from a security position, their purpose being mainly to prevent access or speeding. They are not intended to be used against two-wheeled vehicles. There are a significant number of these used to permit access for emergency or public vehicles, denying access for unauthorised vehicles. They depend on this by automatically rising as soon as the authorised vehicle is clear of it, preventing a following vehicle passing close to the authorised vehicle. Of course, road configuration will depend upon the particular use required of the blocker.

While vehicle barriers are being used to provide temporary protection, government departments are also using steel posts let into concrete foundations and filled with concrete both in order to prevent vehicles moving over or parking on areas of pavement. While these devices will absorb a lot of the energy of a vehicle hitting them, their individual use is suspect in preventing vehicles moving over them due to the difficulty of providing solid enough foundations. However, they are more effective as shown here, en masse, where the collective absorption of energy should stop most four-wheeled vehicles. They will not, obviously, prevent narrow vehicles or pedestrians moving around them, nor do they provide any protection against blast.

Prior to the introduction of the concrete filled steel posts above and the heavy pre-cast concrete blocks below, the means of protecting pedestrian areas or preventing vehicular access across them was with the use of tapered pre-cast concrete posts as shown here. While they provided a visual warning their construction was such that, when struck, the concrete disintegrated as there was little cover over the steel. The post on the right demonstrates this point well. The main security benefit of these posts was that the steel reinforcement provided a degree of resistance the concrete didn’t. To provide better security, concrete must be massed as in the examples below.

For any perceived problem it is arguable that there should be a designed solution, one that resolves the issues in a clean and, hopefully, restrained manner. The two examples above illustrate a common approach to resolving a problem that became evident, or was only realised, some time after the initial construction of the road and pavement. It was a commonly accepted solution: at the time, the adding of barriers of various forms was carried out in a similar manner. In fact this still happens, though it is better avoided, and can be with a little more forethought and planning.

Here is a more recent example that attempts to resolve a problem that must have been evident when the development was planned. The vehicle barrier, partially raised on the right, appears to have been located in the wrong place in relation to the road. In order to protect its flanks, pre-cast concrete blocks have been craned into position around it. Painted in the traditional yellow and black for the sake of visibility, together they form a defensive barrier to vehicles. Regrettably, they also are, psychologically, a visible demonstration that would have been beneficially avoided.

A cleaner, and far better looking, design can be seen in these two photographs. As a part of the original design for the Corniche, these pre-cast units were designed to have three functions. Their main purpose is to act as vehicle barriers, protecting pedestrians from vehicles driving along the Corniche in the first instance, and gaining access to the wide, pedestrian area in the lower photograph. In the upper photograph they also serve as footings for flag poles as can be seen here on the left, and they are both designed at a height that suits a pedestrian needing to rest for a while. The units’ strength lies in their solid construction and firm connection into the ground though, because they are made of pre-cast concrete, they are likely to absorb the energy of a crash less effectively than a steel post. Like their steel counterparts above, neither of the concrete unit systems will prevent two-wheeled vehicles moving between them nor, for that matter, roller skates and skateboards.

Blast

The purpose of keeping vehicles away from buildings is, of course, that buildings tend to be the main targets for those who wish to make a political or other point forcefully. The weapon of choice tends to be vehicles loaded with explosive devices and, generally speaking, the closer it is possible to take the vehicle, the more damage it is capable of inflicting by explosion or implosion, often the two being combined.

The difference is important for it is the former, explosion, that tends to be the commonly considered feature of blast. The positive pressure waves of a blast forces material away from the centre of the blast, creating massive damage both through demolishing the constructional and enclosing elements of a building, as well as through the projection of those resulting broken elements as shrapnel. There is usually a concomitant problem of fire.

Implosion is, perhaps, a misnomer as although there may be negative pressures created resulting from the configuration of the building and the location of the explosion, the term is generally used in reference to the demolition of buildings when it is intended to drop a building on its footprint. The key objective in preventative design is to stop any potential carrier getting into the building. Where this has failed in the past, and a carrier has successfully entered the building, the blast has been confined, the resultant force vectors being multiplied and taking out that part of the structure carrying the upper floors. The resulting implosion or pancaking of the building floors downwards creating maximum damage.

It may well be a prime objective to keep carriers away from the inside of buildings, but considerable damage can be effected by blast located outside a building, even at some distance. In many ways the notes I have placed above relating to delivery and building location are relevant. However, here there may be the possibility of using deflection by the incorporation of shielding or deflecting elements into the design of both the building as well as the landscaping.

Deflection and shielding

Deflection can be used as a design element at any distance from a building, though in practice, the further away the better. In principle any potential source of blast should be contained as far away from a building as possible. At that or those points where blast is likely, elements of building or landscaping can be used to move blast waves away from, over or around the building. There will still be damage but the principle is to try to avoid the projection of material directly at the building.

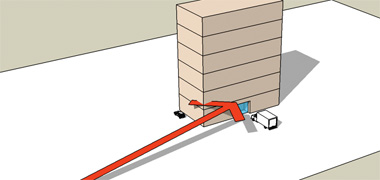

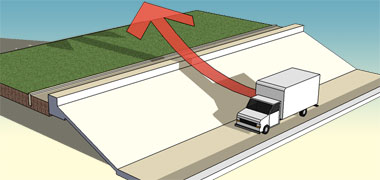

This first graphic illustrates one method by which blast might be deflected away from a building. The origin of the explosion will come, not from the ground below a vehicle, but some point above its bed. It is important that the material and positioning of any deflection device be positioned with this in mind. Here a vehicle has notionally been confined to a single track, an angled surface has been positioned next to it with a strengthened upturn at its top to help move the direction of blast upwards. A step has also been created at the foot of the ramp in order to prevent the vehicle mounting and running up it. There are many ways in which deflection can be created, the main points to bear in mind are that

- the design should not assist a vehicle in moving towards the building or to a more exposed position, and

- any material used to construct or landscape the ramp should not create a hazard when moved by the blast.

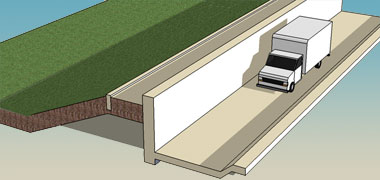

This second graphic illustrates, again simplistically, the shielding of a building by a barrier, in this case, a wall. Again, the principles are similar to shielding. Vehicles are to be contained and directed in their movement and, anywhere along their path the potential for blast striking the designated building directly has to be fully considered and designed against.

In the case of both deflection and, particularly, shielding, consideration should be given to ensuring that, while protecting your own building, neighbouring buildings are not put further at risk by reflected or directed blast. There is an arguable case that shielding and deflection should be discussed with the owners of neighbouring buildings, or at least legal opinion obtained regarding the extent of such discussion or notification.

Building planning and detailing

Some of the issues relating to the planning of buildings have been discussed above, but there are two other points that needs to be made. These relate to the setting of a building in relation to its approaches and the viewpoints from which it might be vulnerable both to missiles and blast, as well as to its internal and external planning.

Planning

Most development planning tends to be organised within an urban street environment, giving close access and significant oblique views. However, where it is possible to move a building away from locations where vehicles move, there is benefit to be derived from organising elements of the building to deflect missiles and, particularly, blast. Angled surfaces deflect and, therefore, reduce the effect of blast. This design treatment operates both on plan and in section.

This implies that buildings likely to suffer attack should best be angled from areas where blast might be anticipated. The difficulties with this are twofold. Firstly, angling buildings on their plots can be wasteful of the site, particularly if the ratio of building to site is high, which it usually is. Secondly, planning authorities nearly always have a countervailing view, their traditional opinions relating to two-dimensional, orthogonal treatments, the emphasis being on the façades of buildings, a tendency which has ruined many a building. This view nearly always requires the façades of buildings to be parallel with the streets they front.

So, if we can’t angle a building to ameliorate its risk from blast, what can we do? First we may be able to take advantage of some of the techniques for isolation, distancing and protection mentioned above, but the secondary design approach would lie in the planning of the interior of the building.

Most buildings have their entrances at the front and highly exposed. The reasons for this have a lot to do with convenience, advertisement and classic tradition. There is no reason this should continue as there are other ways of fulfilling these objectives. The design of entrance spaces are now heavily influenced by the requirements of internal security measures, both hardware and personnel. This tends to create an unpleasant welcome to buildings and one which is rarely successfully dealt with. Perhaps this issue needs to be reconsidered.

Wherever and however the issue of internal monitoring is resolved, it is sensible to ensure that the assailable sides of buildings should contain the spaces and functions which have the least personnel in them. Storage, toilets, mechanical plant handling and the like are obvious candidates for this. This principle also suggests the creation of a double wall – the external wall of the building and whatever protection is built into it, and the secondary wall being the internal wall of the peripheral rooms. This might improve certain aspects of security and safety to the users of the buildings.

An ancillary issue arises from the location of some of the functions within a building. Chief of these is the post room, or whatever name is given to the location of a space set aside to receive and open mail in its different forms. Consideration needs to be given both to its location as well as its protection or segregation from other spaces in the building. The owner or operator of the building will then need to maintain their own precautions within a relatively protected environment.

There are many deliveries to buildings other than mail. These fall into five categories:

- ad hoc deliveries of packages, traditionally brought to the front desk of the entrance and intended for recipients working in the building; in this case they are similar to mail and are sometimes routed there for safety and delivery or, more commonly, sent directly to the recipient, by-passing the mail system,

- supplies of material used by the building, commonly stationery, toiletry and the like,

- equipment and materials brought into the building for the purposes of cleaning and maintenance, both of which might then be removed – which introduces the problems associated with monitoring theft,

- equipment used in the processing of the work of the building, supplies, replacement and the like, and

- food and drink.

All these elements need to have a considered and designated place for

- entering the building,

- being checked for safety, and being

- delivered to the correct address within the building.

These can raise complex issues with the management of the building, but their task will be made more difficult if the basic planning of the building has not already taken much of this into account and disposed the space planning carefully.

Building entrance

There are comments elsewhere regarding some of the issues regarding the entrance to a building. In the main these relate to the perceived socio-cultural importance of having it at the front of the building, being relatively open in design character and, nowadays, having an internal security function. This can be inhibiting and create an unfortunate experience for those visiting though, as is intended, creating both a feeling as well as a degree of security for those working within the building. But access into and within buildings can be extremely complex, requiring a significant investment in electronic systems, both in their installation and in monitoring, the latter mainly a personnel intensive operation with its attendant problem of surveillance fatigue.

It is not my intention to discuss this latter issue in any depth; it is mainly an operational problem. It is mentioned here only in how it relates to planning the building.

We are now becoming used to the fact that only those who have business within a building may have access to it. This reflects on our society as establishing buildings as being generally impenetrable, and encouraging designers to treat them as walled environments, repelling all but those having business within them. This is a policy which reinforces the tendency designers have to create their buildings as objects for observation, but that’s another issue dealt with elsewhere.

Where access is necessary for those working within a building a filtering system is necessary, usually accomplished by means of a smart card system. In order to ensure only one person at a time has access through any security portal, a form of turnstile is necessary. Conceptually, this must allow only a single person through at a time. This can require, at peak periods, a number of units rather than a single unit in order to accommodate the staff leaving or entering the building. A secondary consideration is the need to suite the portals in order that monitoring and control may be effected for all using the building; again a management consideration, but one that

- goes some way to protect property, both fixed and movable,

- protects assets and revenues,

- gives a degree of protection to staff,

- enhances privacy, and

- provides management with some degree of control on its staff.

One of the other uses of entrances, and one that is often not planned for by designers, is its function as an informal waiting room. Staff will often use this space to meet co-workers, wait for a vehicle to arrive or for a visitor. There is a tendency to marry it with a space for informal meetings, particularly where there is a security concern for allowing visitors into the heart of the building.

As I have suggested before, there is no reason why the entrance to a building should continue to take the form it does. It will be interesting if we begin to see new forms of entrance, ones determined by taking a lateral approach to the issues surrounding security.

Structural selection

Conceptually, the structure of a building should be within at least the initial design remit of the designer. The selection of structure can be critical to the behaviour of a building under attack, and it is imperative that the optimal choice is made under the advice of structural engineers, and that the selected structural type is correctly detailed not just from the normal loads a building is anticipated to take, but also blast or stressed conditions.

There might be a degree of structural redundancy as it is important that the building continues to hold up if a part of it is taken away. With columnar structures, the removal of a column should not cause collapse nor, with a load bearing structure, should the building fail when significant portions of that structure are removed. This is more difficult to achieve. Steel or reinforced concrete columnar structures are the usual choice with a significant degree of structural redundancy built in. Of the two, steel frames are preferred though it is common for them to be encased on concrete to protect against failure from fire.

It is also important that floors do not collapse on each other, another common building failure under blast conditions. Sometimes referred to as ‘implosion’ the effect is caused by support being taken away and floors above this collapsing under the combination of their own weight and the live and dead loading they carry. Often punching shear operates where the columns punch through the floors, the failure being at the junction of the floors and beams with the columns.

Means of escape

Whatever happens to the structure, it is also important that means of escape are protected. Under attack many of the features associated with fire and escape are taken out. Water mains will have failed, all advice and directional information systems will have disappeared, visibility and movement will be impaired and there will be significant disorientation for those within and outside the building. It will take time for useful help to arrive and, in the immediate aftermath of the event, it will be imperative that those who can, escape to a place of safety.

For this reason it is worth considering the escape route as having additional protection. This might be translated as their having additional safety provision over and above the local regulations.

Detailing

There is a lot of sense in ensuring no windows face any direction from which there is the potential for an attack on a building. In climates such as Qatar’s, there are many advantages to such an approach, not just from a security point of view, but also environmentally. The only drawback may be considered to be the lack of view, but this can be dealt with in a number of ways. Many people work in buildings from which there is no external view or where the view or views are minimised. The psychological issues are, or will be, looked at on the environmental control page.

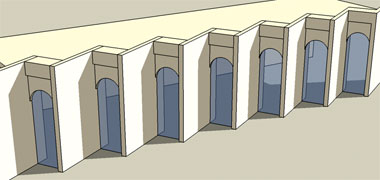

However, windows are traditionally used in buildings where privacy is not an issue, and for these, glass is usually the material for sealing the opening. But glass is an obvious problem as it is intrinsically vulnerable to both blast and missiles. With regard to this part of the notes, good detailing suggests that windows and openings should be masked, perhaps by angled devices. Sketches I have made elsewhere – albeit for environmental or privacy reasons – suggest one type of approach though the suggestion here would be to produce a more integrated design solution rather than rely upon added elements as, perhaps, these two sketches suggest. These examples have been placed here to illustrate the manner in which windows might be shielded from the direction of blast, while permitting light and views to be obtained in the other direction.

Buildings based on a well designed architectural vocabulary can be difficult to achieve, as many new buildings demonstrate. While traditional Qatari architecture has refined an attractive system of collective assembly, it seems to be difficult for modern architects to achieve. Here is a more integrated design sketch illustrating another method to use skewed walls to deflect blast or missiles away from buildings. Intentionally I have made both the sketches above and these to the side as notional concepts; they are not intended to be coherent designs, just assemblies. Considerable thought would have to go into their design before a useful architectural design could be effected. This lower example illustrates a relatively common form of design, usually found when there is a need for privacy or when noise is a problem and needs to be countered by the building form rather than by using modelled berms or a similar landscaping solution to deflect the noise.

With regard to openings in general, all openings should be capable of being sealed closed. This is generally possible with windows, in fact many windows on buildings have no opening mechanism, relying on air moderating systems to provide air of the correct quality to their users. Doors can be closed but are usually not designed to seal. However, the main openings to consider in case of risk are those relating to the intake of air for moderating its quality and characteristics. It should be possible to seal these openings in an emergency.

Not only does the façade of a building need to be considered from the point of view of blast, but also the roof. Designers commonly need to think about wind acting against a façade and being directed upwards, as well as the need to protect against the updraft from strong winds. Under blast conditions it is important that the roof maintains some degree of structural integrity. Thought has to be given to the tying down of the roof, not just considering it as dead loading on the structural system.

The other consideration for protection is in the detailing of the building. It goes without saying, I hope, that the façades of building should be fabricated of material that will resist blast if not missiles, and that the material should be fixed properly. Commonly, many buildings have their final surface treatments added, usually suspended from the structure by fixing lugs or other devices. This tends to be a result of the need to provide a high degree of thermal insulation and air tightness to buildings in order to benefit the occupants and make them more efficient in terms of fuel consumption. Façades such as this are extremely vulnerable and, when struck by a blast, peel off to become secondary missiles.

This may suggest that buildings at potential risk should be constructed of systems that do not have lightweight façadal treatments, but are more solid. Regrettably this is not the case as many buildings constructed of solid material such as bricks or masonry will fragment under blast conditions, the fractured material behaving as shrapnel.

soft and hard systems, public and private systems, deterrence and detection, systems for control, control personnel, socio-psychological problems, system testing, effectiveness, no useful research,

more to be written…

Security | top | Design brief

Search the Islamic design study pages

- Introduction

- Arabic / Islamic design

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 01

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 02

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 03

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 04

- Islamic architecture

- Islamic urban design 01

- Islamic urban design 02

- Islamic urban design 03

- Islamic urban design 04

- Islamic urban design 05

- Arabic / Islamic gardens

- Gulf architecture 01

- Gulf architecture 02

- Gulf architecture 03

- Gulf architecture 04

- Gulf architecture 05

- Gulf architecture 06

- Gulf architecture 07

- Gulf architecture 08

- Infrastructure development

- The building industry

- Environmental control

- Perception

- The household on its lot

- A new approach – conceptual

- A new approach – principles

- A new approach – details

- Al Salata al jadida

- Public housing

- Expatriate housing study

- Apartment housing

- Pressures for change

- The State’s administration

- Society 01

- Society 02

- Society 03

- Society 04

- Society 05

- Society 06

- History of the peninsula

- Geography

- Planning 01

- Planning 02

- Population

- Traditional boats

- Boat types

- Old Qatar 01

- Old Qatar 02

- Security

- Protection

- Design brief

- Design elements

- Building regulations

- Glossary

- Glossary addendum

- References

- References addendum

- Links to other sites