a collection of notes on areas of personal interest

- Introduction

- Arabic / Islamic design

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 01

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 02

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 03

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 04

- Islamic architecture

- Islamic urban design 01

- Islamic urban design 02

- Islamic urban design 03

- Islamic urban design 04

- Islamic urban design 05

- Arabic / Islamic gardens

- Gulf architecture 01

- Gulf architecture 02

- Gulf architecture 03

- Gulf architecture 04

- Gulf architecture 05

- Gulf architecture 06

- Gulf architecture 07

- Gulf architecture 08

- Infrastructure development

- The building industry

- Environmental control

- Perception

- The household on its lot

- A new approach – conceptual

- A new approach – principles

- A new approach – details

- Al Salata al jadida

- Public housing

- Expatriate housing study

- Apartment housing

- Pressures for change

- The State’s administration

- Society 01

- Society 02

- Society 03

- Society 04

- Society 05

- Society 06

- History of the peninsula

- Geography

- Planning 01

- Planning 02

- Population

- Traditional boats

- Boat types

- Old Qatar 01

- Old Qatar 02

- Security

- Protection

- Design brief

- Design elements

- Building regulations

- Glossary

- Glossary addendum

- References

- References addendum

- Links to other sites

Notes on the design of building elements

The purpose of this additional page is to set down notes relating to parts of buildings which require more thought than is normally given to them. You may believe that the notes are very, if not too basic, but there are so many examples of lack of thought in the planning of buildings in Qatar that I thought it warrants setting down some of the issues noticed and ways of overcoming them. It irritates me that so many buildings have elementary difficulties designed into them which create unnecessary problems for their owners and users. The intention is to suggest there more alternatives which will benefit the users of buildings, particularly residences.

The difficulties noticed arise where some elements of buildings are believed to be so easy to deal with that little thought is deployed, particularly in the planning stages of buildings, by many of the designers working on housing in the Gulf. On a daily basis we all deal with the consequences of these decisions unconsciously, but it is a different matter when designing buildings in the Gulf, particularly residences where it makes sense to reconsider our approach. With a little more thought, better and more effective solutions might be provided, to the benefit of those who live in and around those buildings.

It follows that some of the elements of design in the Gulf should not be approached in exactly the same way as those to which designers in the West are accustomed. The reason for this is not just designers’ over-familiarity with many of these elements through daily usage, but for other reasons which have to do with the manner in which they are used in the Gulf. These are, particularly, for:

- cultural,

- social, and

- practical reasons.

These reasons are simple enough to understand and may be similar to issues we have in the West. A major difference, though, is the wealth which is available for building new houses, and the fact that nearly all houses in Qatar have a designer responsible for them.

Doorways

First it should be understood that these notes relate to internal rather than external doors, though there may be some points both have in common. External doors are required to deal with a different range of issues from internal doors, particularly

- security,

- privacy,

- environmental control, and

- identity – the manner in which owners choose to display themselves to the outside world.

Also bear in mind that Islamic houses should be experienced from the inside out, and not as we tend to see them in the West, from the outside in.

Positioning of doorways

Some of the more insidious usability problems we have in the West relate to the positioning of doorways and their treatment. Nearly always the problem has to do with the funds available for building and the small houses we construct. This tends to force the hands of designers who find the easiest and, often, only planning solution results in doorways being located in the corner of rooms.

Not only does this introduce psychological, organisation and usability problems on both sides of the doorway, on a practical level it introduces constructional and detailing problems. The latter are relatively easy to deal with and are, in fact, one of the areas which designers are well equipped to resolve, but often these problems are unnecessary and can be resolved with better planning.

Elsewhere I have discussed the issue of orientation with regard to the approach to a majlis, the preference being that a visitor should find the majlis on his right when entering a hall from the outside of a building. It is also a preference, when entering a majlis at its centre, for the owner of the majlis to be found on the right of the space. My simplistic theory is that this reflects the manner in which fortified buildings were preferably designed in order to give advantage to defenders fighting an invading enemy. But this preference may also be used to advantage in the organisation and relationship of interior spaces. This preference is a cultural issue and may relate to people other than Gulf Arabs.

But there are other cultural and social issues which affect the location and design of doors and doorways. The first is the general practice for doors to be left open. This might be seen as being similar to the trend in the West for the interiors of buildings to be designed in a more open manner. This trend has been examined in some detail, but that pattern is not necessarily similar to the manner in which Arabs use their houses. There may be two reasons for this.

The first is the probability is that it has much to do with the need to feel unconstrained by the containing surfaces of a building. Ceilings are preferred to be high and out of sight. This is a reflection of the manner in which houses were designed and enjoyed in the past, and how life in the desert before that was also experienced.

In addition to this it is notable that residents of houses tend to use the spaces in a different manner from the way in which we do in the West. Although spaces have names associated with them, generally describing their use and with which Westerners are familiar, residents use the spaces freely within the limits of privacy and the constraints of haramlik. It is not unusual for activities to be different from the theoretical names given those spaces. Reinforcing this, my observation is that Qataris tend to move around their houses more than we do in the West. The impression it gives is of their being restless. I know of no work examining the way in which Qataris use their houses so can only go by my own observations. Because of this and the more fluid use of the house, the wider the doorways, the better the spaces can be experienced and used.

It may be a truism, but the purpose of a doorway is to provide access from one space to another. At that place in a building not only can issues such as privacy, security and the like be provided – together with the implicit design opportunities – but there are two other issues which should be addressed:

- the design and artistic opportunities arising from the opening of the walls, and the

- planning associated with the interruption of the walls on both sides of the doorway.

The placement of openings allows opportunity for two types of design decision:

- those relating to the formality of layout, and those

- which give rise to opportunities for longer perspectives than are capable within a closed space.

At its simplest, doorways may be organised in a symmetric or asymmetric manner in relation to the plan of the rooms into which they lead. The majlis system is ideally suited to formal arrangement whether or not the room is being used formally or informally, and whether the owner wishes to sit in the centre or a corner of it. Other rooms may benefit from this consideration. The designer needs to be extremely conscious of the different characters of space which will be created by alternative locations of a doorway. The ability to create different furniture arrangements within that room will be affected by this decision as will the flow of activities into and within it.

While the doorway should be considered from the point of view of its positioning with regard to the spaces both sides of it and its place within a wall, its height and type should also be considered at that time. Generally this should result in doors which are over-sized in order to relate to room proportions; but there is a tendency in Qatar for doors to be no higher than two metres, a design habit which is strongly ingrained in the Western world and which, in Qatari houses, can look wrong. There is no practical reason for this height to be maintained based as it is on standard Western door sizes, themselves based on old legislation.

I mentioned earlier the habit of leaving doors open, but there are three other preferences which Qataris have in the design of their houses:

- the use of double doors where possible,

- having relatively wide doors, whether double or single leaves, and

- having doors swinging to show the rooms immediately, rather than using it to provide some form of privacy as it opens.

It is at least advisable to consider the heights of doors and their relationship with room volumes and, in these decisions, the design of the door architraves and skirtings will also have to be addressed.

Views through doorways

When a doorway is open then there is the possibility for viewers to see from the space in which they are standing or through which they are moving, into the adjoining space. This opportunity should be considered in the design planning of these spaces and the doorway which joins them as there is the opportunity for establishing focal points of interest connecting the viewer with each room. This applies, incidentally, not just to internal rooms within a residence, but also external spaces.

It is evident, and should be borne in mind, that the position of the doorway governs the range of views into one space from another. In a similar way it should be noted that it is relatively common for the owner of a building to want to have some form of visual control over the space outside that room, often a circulation space, and may select his chair with that in mind rather than adopt a more formal position.

Location of doorways near room corners

The most common problem associated with door openings is that which is alluded to above: the placing of the opening too near the corner of a room. With regard to this, the issues to be considered will include but may not be limited to the:

- use of the spaces on each side of the doorway, and the

- necessary furniture to be located in them,

- the size of the door opening,

- the direction of swing of the doors, assuming they are traditionally hung and not sliding, and the

- wall and floor materials on both sides of the doorway.

In domestic buildings the position of a doorway should take account of the possibilities of the furniture arrangement which will or may be located in the rooms adjacent to the opening, both immediately or in the future. This diagram illustrates, notionally, the two alternatives – with and without a return to the wall to accommodate one or more of a number of possibilities. Most commonly the items likely to require consideration will include:

- built-in wardrobes or cupboarding,

- shelves,

- loose furniture such as sideboards, credenzas, tables and the like, or

- seating.

There are, of course, other alternatives to locating doors either in the corner of room or at their centres. The usual alternatives are to have the entrance off-centred on one of the walls – the usual solution – or to have it organised directly through a splayed corner. Additional doors into rooms further complicate layout problems as they reduce the amount of floor area available for furniture both because of the space taken by the second entrance as well as requiring additional space to be made available for people to circulate.

Location of doorways in the centre of rooms

There are few cases where a doorway set into the corner of the room will benefit its layout. Space has to be found within the room to allow those entering to do so comfortably. This means that furniture can not be located too close to the door. It also means that it is the side of the furniture that is being looked at by those entering, and rarely is furniture designed to be viewed in this manner.

However, the difficulty with room entrances occurring in the corner of rooms is that there is nearly always a problem with furniture arrangement near the corner, particularly in majaalis where the usual arrangement is to get as many seats into them as possible. The local market tends to sell seating as sets, there being two armchairs and a sofa in each set. It is sometimes difficult to purchase just armchairs, the preferred solution, but one which provides less seats within a given space. It is also necessary to point out that this type of seating tends to be relatively wide but is the type preferred due to the ability to be able to draw the legs up and use the armrests as misaanid. This sketch illustrates a notional arrangement of the kind found in ordinary majalis with four sets of sofas and armchairs, a number of side tables and front-of-seating tables, a television and a couple of telephones at the most likely places where the owner of the majlis would sit. For illustrative purposes, the door has been omitted. It can be seen that a centrally located entrance would benefit the arrangement.

This, second, notional illustration shows how a central arrangement works better, enabling an apparently more spacious organisation of the room. There is exactly the same numbers of seats though there is a small square table missing compared with the illustration above. The doorway is also a double door rather than a single leaf, again with the doors not shown. In this case the owner is likely to sit in the centre of the far side or in one of the two corners on the right. A central access on the short side of the room would not lose any seating and would probably gain an additional table, if required.

Doors

Again, this might seem a simple subject, and not one worth writing about. Mainly my interest here is in detailing, but only selectively. There will be much which is not covered. But, first, there are one or two points which need to be made with regard to custom and practice, mostly based on observation and experience.

Further up the page I have mentioned the feeling of openness which is preferred by those living in Qatari houses. The larger volumes need larger doorways and doors both for the sense of scale which is given to the interior of the building, but also because of the need which house users enjoy as they move around the building.

Internal doors in Qatari houses are often of very solid timber construction. Where they occur in the public side of the house, for instance the majlis, dining room and associated guest spaces, they may have considerable funds spent on them. Very often craftsmen will be employed to carve traditional patterns on them and, in this, Qatar is well placed as craftsmen, both from within Qatar and from the Indian sub-continent, produce highly skilled work. This example is a hand-carved pattern in teak and shows its origins are not in Qatar.

Scale

Before discussing design issues there is the question of scale which is so important in the appearance of a space. As mentioned earlier, it is commonplace to find doors constructed at a standard two metres height, regardless of the size of the spaces on each side of them. However, it is important to size doors in scale with the space and use detailing to give human scale to the doors. This sketch shows a range of door heights each having the same proportions, and illustrates the effect different sized doors have on the individual. At its crudest you might imagine the low door on the left being an access to a utilitarian space such as a store and that on the right giving access to an important room such as a majlis – though at this scale a pair of doors might be more appropriate. It seems wrong to use a standard height door throughout a building and ignore this element of architectural vocabulary open to the designer.

Single doors

Single doors are the usual solution to resolving the different problems associated with moving from one walled space to another. Security, privacy, aural and visual distraction are all controlled by doors. But many doors do not resolve all these issues as there are bound to be air gaps at the junctions of door with frame and floor; this is mainly an issue of detailing. Doors can be designed to ameliorate some or all of these conditions and are also design objects in their own right.

Double doors

Because of the size of some of the rooms in Qatari houses it has become the practice to provide double doors to many of them. This is also a reflection of the need to move large objects through some doors from time to time. While the use of double doors replicates the traditional practice of having double doors at the entrance to properties, without the provision of an enf they lack the security of a single door. But a more serious problem is the practice of providing a relatively narrow doorway for double doors which means that the width for each leaf is also narrow. This necessitates both leaves being opened to enable users to go through with any degree of actual or psychological comfort. Keeping both leaves open is, in many cases, the usual practice within households, and there may even be an argument for keeping leaves narrow as they will then obtrude less into a room. But often the door and their swings are poorly thought out.

I should also mention the practice there has been in many buildings of having an unequal pair of doors, the smaller leaf being normally fixed top and bottom with bolts and opened only when there is a need to move large objects through the doorway. Regrettably again there is a problem as the size of the opening leaf is often smaller than would be the case if it were a single door. A degree of flexibility will have been provided, but at the expense of every day usability and security.

One final note on doors and their sizing is that some Qatari meals are prepared on very large dishes and need to be moved from the matbakh to the ghurfat al-sufra without being tipped on its side. This will always require double door access and the doors to be held while at least the two people carrying the dish move through it.

Other types of door

The main doors likely to be encountered on the inside of buildings, apart from the above, are sliding or pocket doors and security doors.

Sliding doors are rarely used as their main advantage is in the saving of space. This tends not to be a problem in Qatari houses though I know of sliding doors being used in order to benefit the layout of some rooms particularly of majaalis. Generally, sliding doors are difficult to use and take time to operate. They also have a problem when the handle is not set at the correct distance from the frame in the open position, and the hand can be trapped.

The provision of a pocket for the door introduces a space for vectors to live and breed and is hard to clean. In addition to this, access to the hanging mechanism can be difficult to design and problematic in practice. Sliding doors are not recommended.

Security doors relate, in the main, to doors to strong rooms, safes and safe rooms for refuge, and will be dealt with in the addendum on security.

Finally it is worth mentioning doors which swing in both directions and pairs of doors where one leaf swings one way, the other leaf swings the other.

Doors swinging in both directions can be dangerous unless it is possible to see who or what is on the other side of the door. They really have no place in a Qatari house though I have seen small, slatted, Western-style doors used as a design feature to a kitchen. There seems little purpose to them other than as a marker of an opening as, being open, there is no control on noise, humidity and smell.

Double doors whose leaves swing one way but each in opposite directions, are suited to commercial kitchens where it is necessary to have safe passage through a doorway carrying a tray of food. It is unlikely that this would be needed in a residence but might be worth considering.

Door furniture

Gulf Arabs wear relatively loose clothing, both men and women. As they move their clothes tend to move around and can be easily caught on projections. This is particularly true with door furniture where handles and projecting keys can be a hazard to safe passage through doorways, catching both pockets and sleeves. Abayas are particularly prone to being caught and this problem should be taken into consideration in the selection of handles, knobs and locking devices. The main difficulty seems to arise with specially designed handles which are used with larger doors where designs are created with little thought for their potential danger.

Hinges

Doors tend to be solid and heavy so care has to be taken with specifying the hinges and their location. Mostly doors are swung on side hinges, but this is not the only way of hanging doors. The usual types available to the designer are:

- side hung,

- floor,

- top, and

- the traditional pintle.

But the choice is very much open to the designer and the effect that is wanted. Side hanging is the easiest way of dealing with a door though heavy doors may warrant floor or top mechanisms which have the advantage of avoiding heavy loading of the side door frame. Pintle hinges are a traditional solution to heavy doors and modern versions of them are available.

Side hinges tend to be heavy brass, mainly for their colour than for their structural integrity. Obviously the screws holding them need to be selected carefully and there should be at least three hinges for a normal wooden door, preferably four. Floor and top plates are often steel, but colour has to be considered and, unless the interior design favours silvers, brass might be the better choice.

Good hinges, properly located will allow a door to be opened and stand where placed but rising or falling butt hinges often make sense in order to have doors fall into an open or closed position through gravity.

Handles, knobs and levers

Most houses may have a combination of handles and door knobs scattered through them. Door knobs used to be the main way of opening doors as they had a traditional feel to them, but a number of complaints have been made by people catching their hands on the door frames when closing doors due to a combination of a physically large knob and the operating spindle being set too close to the edge of the door. This was sometimes exacerbated by the rebate on the door being larger than usual, again bringing the door frame closer to the door knob.

For this reason a number of designers specified lever handles which got over this problem, though it introduced the difficulty of catching clothing when the handle stuck out and wasn’t returned towards the door. Many of the handles selected were also heavily articulated stylistically, and this also increased the possibility of fouling clothes. There is no easy solution; each case should be looked at on its merits.

What is important, however, is that the handles should be consistent through the building. The only exceptions would be special doors such as those to majaalis and the like, and those rooms which have a functional requirement which suggests a different solution. For instance doors to store rooms may benefit from lever handles rather than door knobs as would any door where people are likely to move through them carrying something.

Large doors, however, tend to have handles on them, often vertically fixed and used only for pulling the door open. Where used, such handles should be useful and not present the danger noted above. It also makes sense to ensure that the other side of the door is fitted with push plates in order that people will not try to pull open doors which require pushing. It sounds obvious, but is not always attended to.

Where double door have pull handles, and where the doors have a rebate on their meeting edge, only one of the doors will open when pulled. Whichever door is selected as the opening one of a pair should be consistent with all double doors in the house. One solution to this problem has been to do away with the central rebate. This permits either or both doors to be opened but has the disadvantage of making less of a seal. Where privacy and noise are not problems, this might be a sensible solution, but clients should be aware of the issue as later attempts to add sealing strips may be difficult and not as effective as a properly designed and installed strip initially.

In all cases, lever handles and door knobs should be easily held and turned or depressed in order to open doors.

Door stops

Door stops are one of those odd design requirements that people tend to forget about in the design stages and when installed later, tend to look like the afterthoughts they are.

There are two types of door stop to consider, both of them designed to prevent damage to either the door or wall, or both. They are:

- those which are fixed on the floor and are intended to stop the door opening too far or hitting a wall, and those

- which cushion the handle and prevent it hitting and damaging the wall.

In addition to stops which are designed to prevent doors opening too far, should be added stops which are designed to keep the door open in the short or long term. Most doors are allowed to swing on standard hinges though falling or rising butts are sometimes used in order to return a door to a closed or open position through the use of gravity. Standard hinges used in conjunction with a well balanced door will permit the door to stand at whatever position it is moved to, but often this is not enough and, as a security, a stop is required to hold it at a fixed position. I have seen hooks and bolts used for this but they are not really the best mechanism. It will often be better to use door swing mechanisms to hold doors open at a predetermined place, usually at right angles to their closed position.

Door stops which are located in the floor can be dangerous as they are easy to trip over when the door is closed. For that reason they are best used when an item of furniture or, better, built-in furniture or a wall, are located adjacent to them, in order to keep people away. Nevertheless, they are still difficult to items to deal with and work better when they have a relationship with a marble floor pattern. Cutting them into carpets is usually a poor solution unless the carpet is properly trimmed around them. Whichever the solution to a floor-located stop, it is important that the stop and fixing are selected with sufficient weight to withstand the weight of the door striking them.

Door stops fixed to the wall are a simpler solution but can only be located where the door – most usually the handle or knob – would strike it. A traditional solution was to have a chair rail around the wall which would act not only as a way of preventing chairs damaging the wall, but also the doors in the room.

Locks and bolts

Qataris have an interesting attitude to locks within houses. Generally they are not liked though certain rooms may require them. The most obvious of these would be:

- a study or office – this usually being associated with the guest accommodation and the men’s side of the house,

- storage areas where items of value might be kept,

- strong rooms which, by their very nature require heavy security,

- safe rooms, which are dealt with elsewhere, and

- bathrooms.

In all cases appropriate security has to be provided by the locks, and the keying system discussed with the client. Traditional keys are still favoured but electronic solutions are becoming more advanced and likely to take over from mechanical systems, particularly if the whole house is keyed and suited.

Bathrooms should be lockable from inside and should also enable external access in the event of an emergency. It is better that a lock is used rather than a bolt which may not be openable in emergency from outside the room.

From the design point of view, escutcheons, finger plates, push plates and the like should be carefully considered both for position as well as design coherency. Where possible they should be integrated.

Finally it should be noted that the striking plate of locks and, particularly, latches can also present a problem to passing clothes. They tend to have a part of them projecting beyond the door frame into which they are set, and the less expensive ones can be quite sharp. They all, however, present a hazard if not properly designed for and fixed.

Bolts are used with all double doors, usually fixing into both the head of the door jamb and into the floor. They have to be reachable and should be of good quality as the cheaper versions can be difficulty to manipulate. Usually they are set into the door jambs in order to hide them. As floors are usually of marble or stone, the receiving hole should be carefully located and, preferably, lined with a suitable metal in order to prevent cumulative damage to the marble from the operation of the bolts.

Detailing of doors

Again, this note deals with something which might appear obvious. However, there are so many door arrangements which have not been well detailed and which cause a variety of problems, that it seems sensible to note the problems and look at possible ways of dealing with them. There is discussion above relating to the manner in which doors open to the benefit or disbenefit of the room layout beyond. This is an expansion relating to the detailing of the doors.

Materials

The majority of residential internal doors in Qatar are constructed of timber, usually a hardwood. The joinery industry is skilled, the materials are usually well sourced and door and frame assemblies properly made. At the bottom end of the market, however, softwood and plywood still form the basis for a lot of door assemblies and these doors tend to be poorly constructed and installed.

Because many buildings are individually designed, there is scope for doors to be created in any style and size the designer or client requires. The important doors in a house, at least those which can be seen in the public side of the house together with the main bedrooms and women’s saala, are likely to be specially designed.

Styling tends to follow Western designs rather than having something of the character of Qatari design in them, though architraves may do so, particularly if naqsh is used. Doors are normally panelled with structural junctions reinforced by decorative beading. Finishing of these doors tends to be both left in the natural colour or, as has been very popular, lacquered with a high gloss finish, usually in a light cream colour, but sometimes in quite strong colours. Its major problem has been its ability to show scratches as well as chip on the edges.

Other materials are used for certain doors, particularly those associated with storage or security, but they are very much in a minority. Aluminium framed glass or panelled doors are found in some houses, but tend to be seen as a down-market solution.

I should also mention that some of the important doors may have glass in them, and may even incorporate metalwork, particularly brass, face applied or inlaid. Where glass is used it should, of course, be safety glass – toughened, wired or laminated.

Sealing materials

The interiors of Qatari houses tend to be dominated by hard materials. With the exception of carpets and some soft furnishings there can be considerable noise within them and this can cause nuisance. Very few doors are constructed with this in mind and there are often large gaps between the bottom of doors and the floor. It has been said to me that the reason for this is to accommodate the drop of the door with time. There may be some historical truth in this as glues used to allow slippage with time due to houses being relatively hot, but those days have for the most part gone and this should not be a problem.

There is no reason why doors should not have some form of sealing strip on the bottom of their doors to reduce air-borne sound unless, of course, they are located over carpet when the problem is considerably reduced.

The other potential area for air-borne sound is the meeting stiles of the door where, sometimes, there is no rebate made in order to allow either leaf to open when pushed. Again, this can be helped by the insertion of a brush strip of similar element.

It should also be noted that an intumescent strip will be required in doors which protect a route to safety in the event of fire.

Adjacent materials

The first thing to know in the detailing of doors and their openings is the character of the materials adjacent to them. On the ground floors of most Qatari houses the floors are likely to be hard and take the form of marble or terrazzo. On upper floors this may also be the case but fitted carpets are often laid and used with Persian rugs. These two conditions – marble and carpet – give two different conditions at the foot of doors.

Walls are usually constructed of concrete blocks and finished with cement render or, on higher quality work, plaster. This is then painted or, in some cases, wallpaper is applied. A better quality finish is obtained where fabric is stretched over the wall. There are, in the main, two different systems used to effect this though, for the sake of these notes it is only important to note that the fabric will be located about 15mm away from the finished wall. There is, of course, no reason to finish a block wall if fabric is to be used, but the practice is to do so in Qatar.

At the foot of walls skirtings on the ground floor, and where the floor finish is marble or terrazzo, are usually the same material. Where carpets are intended, skirtings tend to be hardwood though this might also be the case with a marble or terrazzo floor. Hard materials make more sense as marble and terrazzo floors are washed, usually every day both for cleanliness and to help keep the building cool. Timber skirtings will suffer from this washing.

The public suite of rooms which comprise the madkhul, majlis, ghurfat al-sufra and maktab will usually have the same floor material running through them though nowadays there is a tendency for the majlis to be carpetted. This probably has as a lot to do with people being more comfortable sitting on a carpeted floor to eat. Even where this is the case there is the possibility that the madkhul and ghurfat al-sufra will have a marble finish. It may seem counter-intuitive but upmarket dining rooms tend to have marble floors and normal dining rooms carpet.

Other rooms of the suite such as the hamaam and the room where coffee is prepared may have more functional materials on the floor, but these will definitely be hard.

Thresholds

Where there is a change of materials it is important that the floor levels are carefully considered at the threshold between adjacent rooms. The design issue of materials running through is not an issue here, but the relative levels and the position at which change of materials happens, is as they affect the comfort and safety of people moving across the junction as well as the position and detailing of the door and frame. One neat way of dealing with this is the practice of using a piece of marble across the threshold in every case, its only detracting features being the air gap and the visual discontinuity of materials between rooms when the door is open.

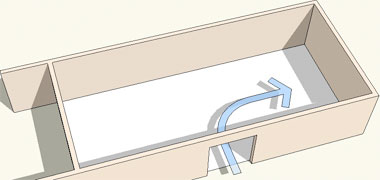

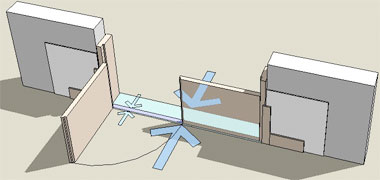

Usually a change of materials is planned to take place below a door. This will give about 50mm within which the change can be detailed. It is surprising how often the change is not accommodated within this space. Change must happen within the limit of the two large blue arrows here, but should really be confined to the space between the two smaller blue arrows which define the limit of the thickness of the doors.

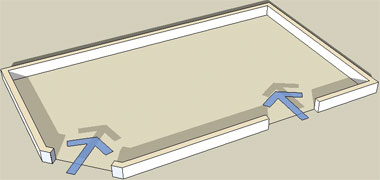

If the space between the two arrows is used to make the change then it is preferable that the whole of that space is taken by a different material such as marble. If that decision is taken then a single stone should be placed there or, if this is not possible, three stones, not two as it is considered wrong to divide a space in two. This principle applies in many other instances such as stair treads, window cills and the like.

Door swings

Very few designers seem to consider the manner in which doors swing until too late in the design process. It is obvious that door swings are a consequence of four issues:

- the size of the door or doors,

- their relationship with the wall in which they hang,

- their relationship with walls at right angles to the wall in which they hang, and

- furniture and furnishing arrangements on both sides of the door or doors.

There are three factors which govern the distance the sweep of a door swing can travel before meeting resistance:

- the position of architraves in relation to the door hinges,

- the location of returning walls and furniture, and the

- position of skirtings, which tends to be the factor most frequently not considered.

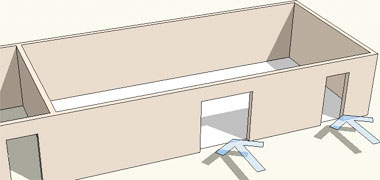

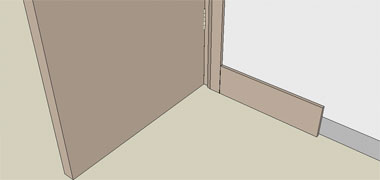

It is imperative that the door is able to open to its designated position whether it is to be held by a door stop, gravity and friction, or a door swing mechanism. Whichever is selected, a door leaf should not be damaged by striking a fixture or fitting, nor should it cause damage. This first illustration shows a door open at right angles to the wall in which it is set. A simple architrave masking the junction of door jamb and plaster is shown, as is a skirting of the same thickness as the architrave.

Here is a detail of the most common problem affecting the opening of a door. The detailing of the relationship of architrave to wall and door jamb is simply made and represents a common arrangement. The door will open to about 160° in this particular case until it strikes the architrave. The architrave should not be relied upon to stop the door swinging as the force exerted laterally on the screws by a strong door will be considerable, and the consequent weakening of the hinge screws will cause the door to sag. In this case it is important that the door is stopped from swinging as far as 160° in order to protect both the hinge screws as well as the architrave from being damaged.

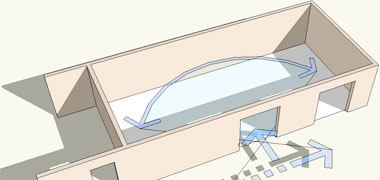

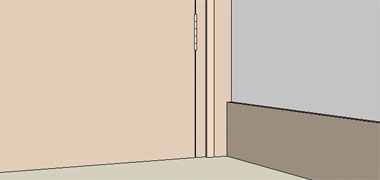

As was mentioned above, it is better practice to use a marble skirting with a marble floor. However, marble skirtings tend to be thicker than timber skirtings in order to avoid mechanical damage, and there can be problems with doors if the junction of skirting and timber architrave are not well considered. This detail is relatively common but should be avoided as the marble sticks out further from the wall, reducing the door swing to around 140°, and creating the possibility of uneven straining of the door if it is to strike the skirting only at the bottom, compared with striking the length of the architrave. For clarity of the skirting and architrave junction, the door has not been shown, though the notional swing has.

The most common way of detailing a door in the corner of a room is shown here in the upper of these two illustrations. In fact there are uglier ways of detailing the corner but this detail is relatively common. Its difficulty is that, when the door is in the open position and lies against the returned wall, the handle or door knob are likely to project further than the width of the door’s architrave and, with or without a door stop, the door will not open a full 90° and will not look right.

The solution is to have a deeper reveal but that brings up another problem, that of having only a small area of wall behind the architrave which, again, will not look right. It is shown here in its smallest return where the depth of return is that of the depth of the skirting and where that depth is sufficient to allow the door to open to 90° with the incorporation of a door stop.

Even if some effort is spent detailing the architrave around the doorway there will still be a visual problem detailing a door in the corner of the room. In this sketch an effort has been made to integrate a marble skirting with a naqsh or marble architrave, and to take their dimensions into a trim for the carpet. The open door leaf is shown open at 90° though in reality it would be more likely to be open further to allow easier passage into the room. But it is evident that the doorway still doesn’t work properly and can be seen to be squashed into the corner of the room. Yet this is the manner in which many doorways are detailed, even into important rooms. The lower of the two illustrations shows how much improved is its location when moved away from the corner of a room.

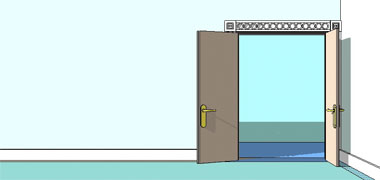

Finally, here are two sketches of the same corner. The first sketch illustrates that, despite what has been written above relating to the unfortunate effects associated with door located in the corner of a room, the open doors will actually improve the appearance of this by hiding the architrave and wall detail. For illustrative purposes the leaf on the right is open at 90°, the leaf on the left at 30° from the wall.

The same sketch, this time with two chairs of a style popular in formal majaalis also illustrates how the doors must be considered in laying out the furniture in the room if they are not to create too much of a problem for those entering and leaving the room – and how the floor and wall surfaces of the two space each side of the doorway should be considered, particularly where they meet at the threshold.

Bathrooms

The fitting out of the new bathrooms was with suites bought in from the large number of agents who sprang up to supply the nascent housing industry. Bath, wash hand basin and toilet bowl were the standard items, all located in the bathrooms though some of the earlier housing had Asian toilets supplied. Where the house plans had a separate lavatory, that was usually Asian. However, there was no consideration given to the orientation of the toilet or lavatory, this reflecting the direction in which the housing layout dictated the house to be placed. In some of the housing for expatriates, bidets were also supplied as, generally, the bathrooms were of sufficient size to contain them, and agents pressed the industry to include them. Despite the relatively expensive items being fitted, not a great deal of care went into the installation of fittings, as can be seen in this photograph of a new item being inserted into an existing bathroom.

Each bathroom was laid out in the same way with the bath along one wall and a filling piece at the end to make up the difference – usually up to about 750mm – between the length of the bath and the width of the room. A pedestal wash hand basin and toilet completed the set with an uncovered hot water heater situated above the bath. This practice was eventually deemed dangerous following a number of accidents scalding users. A serious attempt was made to encourage the units to be enclosed and, preferably, located elsewhere, but this was not altogether successful.

Here you see the detail of the end of the bath and part of the filling piece of a typical installation. This area is commonly used to locate the bits and pieces needed by those bathing, but requires the bather to stretch behind, an operation which can be difficult. The workmanship leaves something to be desired as you can also see an unusual solution to the tiling of the work-top with inset wash hand basin where a twenty millimetre strip of tile has been used to complete the tiling.

Lack of design consideration allied to poor detailing and workmanship can create visual problems in many areas of the house, but can make or break the appearance of a bathroom. Here, apart from the broken lavatory seat hinge, there is face fixed plumbing and an extremely unfortunate junction of the lavatory unit trap to the wall. Note also the design decisions taken with respect to the tiling under the bath. The reason for this lack of concern was that there was usually nobody within the contractors’ organisations with an interest in design, even when the housing under construction was intended for up-market expatriate use.

Here is the photograph of the bathroom from which the above details were taken. In it you can see that the bidet and lavatory are of slightly different colours and that the junctions of the flooring and vertical tiling do not match. One of the most important details to note is the central floor trap which is essential for taking any overspill there may be from the washing activities as well as being useful for washing down the bathroom as well as areas outside the bathroom if they are also terrazzo or a similar finish.

As might be anticipated, bathroom suites sold in Qatar are sourced from all over the world. Many bidet units come with an effective shower in their base, however some countries will not permit this feature as it is considered to be potentially dangerous. Other units have a waterfall or spout system which can be useful, but it seems relatively rare.

It is necessary to have a washing facility in the bathroom and this is either provided with a bidet or with a separate spray unit. In the latter case the bidet may be omitted. These spray units are plumbed into the wall adjacent to the bidet, are linked with a flexible hose and the on/off control is hand operated supplying cold water only. Generally they are situated on the left hand side of the bidet or w.c. as is shown here, though it would more sensibly be located on the right due to cultural requirements. Confirmation should be required from a client as to which side of the w.c. or bidet such a unit should be located, as well as to where a soap dish and towels should be placed. Bear in mind that bathrooms and washrooms tend to be very wet areas.

As in the West, there is always insufficient space for the various items that are necessary for washing and beautifying which means that the space behind the bath tends to be used for storage.

There is an issue relating to the use of bathrooms that I won’t go into here but will deal with when discussing kitchens, and that is the use of bathrooms to wash large pots which will not fit in a kitchen sink.

Before moving on to the use of toilets I want to mention some issues relating to the positioning of bathrooms as this is not understood by many designers – and some clients, until it’s too late.

In the West – after toilets were brought into the house – the optimal house used to be designed with three bedrooms and a single bathroom, sometimes with a toilet in a separate room. The toilet usually had no wash hand basin associated with it which required those using the toilet to then move to the bathroom to wash their hands, assuming the bathroom was free. This state of affairs changed with increasing wealth when two trends were seen:

- the inclusion of a separate washroom, usually downstairs, and

- the incorporation of the toilet into the bathroom.

This had the perceived advantage of providing an alternative toilet as well as allowing visitors to have access to a toilet and wash hand basin without using the family’s bathroom. In fact the room, always located downstairs, was usually named the Guest washroom and tended to double as a cloakroom if there was space to hang clothes out of the way of water.

With time and increasing wealth another bathroom was added, usually as an en-suite addition to the master bedroom, the second bathroom being shared by the occupants of the other two bedrooms. Where space was at a premium the en-suite bathroom might only have a shower rather than a bath, a bath being provided in the second bathroom.

In those parts of the West where space was not at a premium and where there was more disposable income the number of bathrooms grew and, in some cases, each bedroom was provided with a bathroom. In the Gulf there has been a similar pattern of development starting with, as I described above, a bathroom to be shared by three bedrooms and a washroom to be used by members of the family and guests. Nowadays there are far more bathrooms in most houses, and a large number of en-suite arrangements.

However, it should be borne in mind that, for cultural reasons, en-suite bathrooms are not necessarily the most useful facility, and consideration needs to be given to cultural and family sensitivities prior to planning houses. Below, a little more has been written on this subject.

Bathroom considerations

The notes above relate just to the bathroom, but I should add notes on how bathrooms are used. The most obvious considerations are not dissimilar from those which need planning for in Western bathrooms. But the most significant differences can be in the amount of toiletry to be found in them, and the manner in which they are used when friends are entertained in their bedrooms by teenagers, particularly female.

Before I get onto the considerations for bathrooms there is one decision which has to be discussed with clients, and that is the division of tasks between dressing rooms and bathrooms for this defines where some of the elements will be located. The most obvious of these is the area where women will apply make-up, and the manner in which people prepare themselves for going out into the private and public world. Generally, bathrooms have taken over from dressing areas as specific spaces, but this could be because dressing rooms have fallen out of favour and bathrooms have become larger.

Western bathrooms seldom have provision for the amounts and character of items normally required in them. This is even more true in the Gulf. At its simplest consideration has to be given to five issues:

- furniture,

- equipment,

- toiletries,

- display, and

- storage.

The first decision on what furniture is required in a bathroom depends on life style and decisions set out below for ensuite requirements and dressing areas. Associated with this will be the need to consider functions which depend on tradition, wealth and upward mobility. At its simplest this will require a decision on the provision of:

- bath, and/or

- shower facilities

within the bathroom or within separate facilities, even separate rooms. This can be further divided into decisions on:

- separate showers, or

- baths with a shower facility.

In upmarket properties there are likely to be other decisions to make for activities which might be associated with bath, shower and dressing facilities. The most common of these are:

- home gymns,

- saunas, and

- swimming facilities.

I won’t go into any detail for these facilities. They are mentioned here only as a reminder of the need for consideration with a client, as there will be planning and layout decisions to be made flowing from those considerations.

It is astonishing how many products are used in bathrooms. If the bathroom is shared, the problems multiply.

Work areas

This photograph illustrates an up-market vanitory unit, the type of facility that is provided in many hotels and is replicated in a number of homes that have the space for it. The reason for their introduction is that wash hand basins have little in the way of space for the various elements that are used by those washing and grooming; vanitory units provide a larger area for placing items that are needed for these processes. This type of design is desired by many clients and provided by most designers without too much thought being given to the processes to which it responds. Yet this type of design, while visually appealing to many, is not suited to everybody and illustrates a number of issues.

The first relates to there being two basins. The rationale is usually given that it gives two people the chance to wash at the same time, commonly the hands and face, an activity that does not take all that long for some but, for others may be a lengthy process as men may use it for wet shaving. Women are likely to need it less, though it will certainly be used when taking off make-up. Generally speaking, other bathroom activities do not need two basins, though it is probable that young people are more likely to wash together than might older persons.

Mirrors are extremely important in bathrooms. They are not necessarily required to be full length but are usefully located along the back of a vanitory unit. Wherever they are located, it is essential that suitable lighting is provided with them. Additionally, the type of shaving or magnifying mirror shown above is a good start for men where shaving is necessary – the bottom of one can be seen top left – and this may also be used by women. But in the latter case the character and location of the lighting must be carefully considered. A good system should allow a woman to put on make up suited to the lighting in which she will be seen. At its crudest this will be either for natural daylight or for tungsten or other artificial lighting indoors. The type of lighting associated with actors’ dressing rooms is eminently suitable.

The next issue is the amount of space needed for items on the vanitory surface. Here there appear to be jars containing cotton wool, wipes and small soaps, together with a hairbrush, flannels, hand towels and glasses. What are not shown are nail brushes, manicure implements, combs, toothbrushes, shaving accoutrement, make-up and its applicators, shampoos, medicines and a variety of other items that different people have in their bathrooms. Some of this can and, in the case of medicines, should be located in a safe cupboard, but most people leave them on the work surface along with perfumes, after-shave and, often, a stand for jewellery.

But, more than this there are an increasing range of electrical items such as toothbrushes, razors and, particularly, hair dryers that need to have a permanent location as well as creating no danger to their users from an electrical shock. These items are not necessarily mounted on the vanitory unit but might be wall mounted close enough to be used in conjunction with the mirrors. There is also a tendency to want refrigerators in bathrooms, adding to the potential danger.

There might also be consideration for the washing, cleaning and changing of babies. This is not the place to set out the specific requirements, but the main bathroom is often the place where a young mother will look after her baby, yet is unlikely to have the range of design elements and the degree of safety required for the related tasks, nor necessarily the concomitant storage and disposal facilities. In many Qatari houses, the changing of babies may well take place in a maid’s quarters.

It must be realised that bathrooms differ in their requirements far more than most people understand, and that these requirements will differ over time, perhaps to a greater degree than other spaces in a house.

En-suite bathroom facilities

Much of what I have written above relates to en-suite bathrooms, but there is one aspect of them that should be noted, and that is their planning in relation to the bedroom, dressing room or sitting area. For reasons I can never understand, this rarely is satisfactorily resolved. It is a common problem in many new designs and one which, once constructed, is difficult to mitigate.

The photograph above illustrates an almost universal design relationship between a bedroom and its en-suite bathroom. This is the view from beside the bed, but is often similar to the view from the door entering the bedroom. It is thoughtless and unsightly. It is not pleasant look at a toilet or even a bidet from the bedroom, particularly from the bed. Doors to en-suite bathrooms are commonly left open or ajar and it should be a design consideration that not only will there be a design relationship between the two spaces, but also that the view is not unpleasant. This can often be effected by the swing of the door, but it might be better made by considering the layout of the bathroom with this in mind. After all, designers are supposed to think of this relationship in the manner in which other spaces work together, so why not between a bathroom and bedroom?

A more important consideration for older people and Muslims is whether or not there should be an en-suite bathroom in the first place. Bathrooms are invariably hard finished and relatively bright. Using them at night creates significant disturbance to those in the bedroom, even if the door is closed. In this case it is preferable to have at least a lobby between the two spaces, perhaps designed as a dressing area. It is also necessary for many Muslim couples to spend time apart during the month when, again, the en-suite bathroom is not a workable solution.

Use of toilets

There is considerable debate as to the correct procedure for using toilets in Islam. Over time a complex process has been established, but some of the elements of this are no longer considered necessary by some as it is argued they relate to conditions which no longer exist with the development of sanitary bathrooms. I shall deal here only with the main issues relating to the provision and layout of bathrooms, not to the more debatable religious requirements.

First, the toilet should be located in such a position that a person using it does not face, nor has his back to, Mecca, the direction of prayer. In effect, the safest way to position the toilet is so that a person using it faces 90° to the direction of Mecca.

The toilet should be located in such a place where access to it will not create privacy problems within the layout of the house, and its use will not cause embarrassment.

Next, it is preferable to have a toilet in a separate enclosure from a bathroom. This space should preferably include a:

- wash hand basin supplied with hot and cold water,

- an Asian toilet supplied with flushing mechanism,

- a stand point supplied with cold water positioned about 750mm above the floor and within reach of a person using the toilet; this will be used to supply either a hose on a flexible line or a tap used to fill a water jug,

- a toilet paper dispenser also within reach of the toilet,

- a hook for a towel to be hung, also within reach of the toilet,

- a bar for a towel to be hung within reach of a person using the wash hand basin, and a

- coat hook near the entrance on which to hang an abaya or bisht.

The room should generally be ceramic or stone tiled on both the floor and walls, and the floor should be laid to fall away from the door in order to lead water back to drain into the Asian toilet or, where it is intended to supply a pedestal toilet, to a floor drain supplied with a water trap to prevent smells, although it will not prevent access to some vermin for whom different provision should be made.

Good light and ventilation are necessary with, perhaps, artificial ventilation venting to the outside. Where there is a central air-conditioning system operating, air from the toilet should not be re-circulated. This is also true for bathrooms where the air is likely to be very humid.

Where a toilet has to be located in a bathroom it is preferable to have a pedestal toilet rather than an Asian toilet.

The above suggestions may seem obvious to many designers, but the reason I have set them out is based on observation of toilets in both public and residential locations.

Partly this is due to the way in which Asian toilets are installed together with their necessary additional components; partly this may be due to use; and partly there is a more difficult maintenance and cleaning problem to deal with as a wide area around the toilet is liable to becoming wet. These two photographs illustrate what commonly happens in a poorly designed and maintained toilets. This may seem to be a criticism but bear in mind that medical advice is that the Asian toilet is considered to be better than a Western toilet from a personal health point of view. This is due to the individual’s position in use.

What is particularly noticeable are the problems caused by poor tiling and maintenance.

The key to designing Asian toilet enclosures well is in positioning the unit correctly, providing all the necessary adjuncts for its use in sensible locations, and establishing smooth detailing. Materials for its cleaning should be provided nearby and it would certainly help if the designer has experience of their use.

Kitchens

As with bathrooms, kitchens in the first Qatari houses were laid out little differently from Western kitchens. The units were arranged peripherally with a standard single sink basin and draining board arrangement, the hot water cylinder supplying it being located in the nearest corner of the room, and a space being left for the gas cylinder operated cooker and electric feed for a free-standing refrigerator. A small number of socket outlets were supplied for electrical equipment, often a solitary double outlet supplied this need and the refrigerator. There was no consideration for the principle of work flow and often electric outlets, sink and cooker were dangerously close to each other.

A single light was provided in the centre of the room, patently insufficient to give good lighting to the tasks carried out in the kitchen and, of course, located in the worst position for carrying out tasks on the peripheral work surfaces.

The kitchen was large enough to accommodate a small table and four chairs and, usually, there was a single window and a standard door giving access to the outside. As the house was always raised above the ground in order to give some protection against flooding as well as taking consideration for the importing of sweet soil to form a garden, the area immediately outside the kitchen door was usually a small quarter landing with a number of steps leading down to the garden level.

There are a number or problems with what I have described so far. Apart from technical issues, these problems are of two types: those relating to the sensible layout of a working kitchen, and those relating to traditional practices. Neither of these seemed to have been properly considered in those early kitchens, and this has led to the problems being reinforced in more modern kitchens.

The first difficulty relates to local cuisine and the equipment needed to create it. Traditional meals can require considerable preparation and, with large families or many guests to feed, kitchen pots and pans can be large. This requires:

- the ability to fill containers from a sensibly located water tap. Where this is not possible in the kitchen due to the positioning of the sink tap it has to be effected outside or from the bath tap,

- the ability to wash large pots. Generally these can not be accommodated in a normal sink and need to be taken outside for washing, unless they are washed in the bath,

- a large stove in order to take both large pots and pans as well as a larger number of pans than might be the case in a Western kitchen,

- safe storage with blow-out panels for the gas bottles which are preferred to fuel the stoves,

- space for a large, free-standing refrigerator as well as the possibility for a second refrigerator outside the kitchen for soft drinks as refrigerators are constantly being opened and closed for access to soft drinks,

- considerably more storage than in Western kitchens to take account of buying items such as meat, soft drinks, fruit, onions and rice in bulk,

- storage for all the kitchen equipment,

- large working surfaces for preparation,

- a floor drain to accept water from washing down the kitchen and floor, and

- an effective ventilation system.

You should also note that kitchens, besides being hot and humid areas are also extremely noisy both because of the hard surfaces and the cooking and preparation processes, but also because of the number of people likely to be using it.

All this points towards the need for a better relationship with the outside and, as I have described, this was ignored in the first new houses and, to some extent, still is. It is necessary for there to be:

- good access through the doorway to the outside. This means that the door has to be wide enough to carry through it large and heavy items safely, sometimes an exercise that has to be carried out by two people,

- a work space provided with drainage and a standpoint at about a metre off the ground and accommodating a hose pipe in order to wash large pots and pans,

- an area for cooking large meals in the traditional manner, and

- shade.

I should also add to the comment I made on the heat of the kitchen. In modern houses with central air-conditioning there is sometimes the inclusion of the kitchen in that system. There is no sense in this. If the kitchen is to be air-conditioned it should be a separate system venting to the outside of the building in order not to add excessive humidity to the house system, as well as smells. It will also have to be readily accessible for maintenance.

Which reminds me that there can be a serious problem with the smell from refuse. To some extent this can be dealt with by careful location of refuse storage areas, and keeping them washed down daily in summer, but some people ensure that these refuse areas are air-conditioned.

Elsewhere I have discussed other issues relating to refuse, particularly with regard to recycling. Suffice it to say here that in the future there is likely to be a need for households to separate their refuse into organic, plastics, metals, glass, cardboard and recyclables, which means separate containers for each of these items, and sensibly located and sufficient space.

The second issue relates to cultural practices, and here there has been blind acceptance of the Western kitchen layout without consideration of the traditional ways of producing food. The preparation of food in the Gulf culture reflects the manner in which the family live and work together. There are many notes on this on the socio-cultural and Pressures pages.

In its essence, the women of the family are all involved in the preparation of meals, and this is carried out in concert. It is a strong element of the social bonding of the household. Both physically and psychologically these activities are carried out together as a joint social exercise, facing inwards around the food and its associated containers and processes. To the observer it can be a noisy and apparently unstructured operation, but families are proud of their food and all develop personal recipes for traditional meals, the contents and amounts they jealously guard. Western kitchens, in contrast, are designed more for individual activity, those using them facing outwards towards the peripherally located equipment.

It is notable in the West that there is a desire with those who have the space to be able to prepare and cook food while talking to family and guests in an area adjacent to the kitchen area. This is different from what is theoretically necessary in Qatari kitchens.

For this reason it appears to be a far better idea to install a central kitchen unit system so that the family can work around it, facing each other. It is also necessary to consider more commercial units capable of receiving the larger pieces of equipment.

I should also add another note that relates to the height of kitchen equipment. Standard kitchens bought in from the West tend to be based on the heights of Westerners. Qatari women tend to be a little smaller than this and I have noticed the difficulty some have in using work surfaces at relatively high levels. This is exacerbated by the fashion to use thick cutting blocks which add to the height of the work surface. It has to be borne in mind that kitchens should be more carefully considered than they used to be, not just from the look of it but particularly from the practical requirements of the individual households.

Having said that I have also noted elsewhere the different work and educational imperatives which are now having an effect on the way in which families live. This has three effects:

- individuals in families now tend to need their meals at different times due to the need to the different programmings of education institutions and public and private workplaces,

- high disposable incomes together with the massive increase in the number of fast food outlets has meant that more families and individuals eat out or buy prepared food to be consumed at home, and

- this disposable income has meant that more kitchen devices are being purchased with space having to be found for them in the kitchen.

This means that the requirements of kitchens now reflect the changing society more than is likely to be the case in the West. The pressures at community and personal levels are very different from those of the traditional society of a generation or two ago and are likely to be in disbalance for some time. That discussion will be made elsewhere; here it is only necessary to note that it is not as easy to lay out a Qatari kitchen as it is a Western one.

Laundry

Western designers tend not to think about the problems of laundry because, in the main, they don’t have the experience of it in their home countries. In Britain, for example, the standard provision for washing clothes used to be a washing machine plumbed into the kitchen. This is often the standard still used though sometimes with the addition of a tumble drier. The days of hanging out washing to dry outside has gone – just as the practice of hanging it to dry in the kitchen on a mobile ceiling rack went before it. Better Western practice tends now to be the provision of washing machine and tumble drier in a separate space related to the kitchen together with other related facilities which I will discuss later.

Arab dress has been described elsewhere but, for these purposes can be thought of as a long shirt – thub, vest, long underpants – sirwal, and socks for men, together with ghutra and kufiyah. Women wear similar clothes to those worn in the West, though with longer and more voluminous dresses and, often, more expensive materials.

Traditionally, everything used to be washed when dirty and it is only in the past twenty or thirty years that dry cleaning has become a reality enabling clothes not easily washable to be dry-cleaned. The first dry-cleaners in Qatar were extremely difficult to control, often damaging the clothes sent to them and creating a smell that no amount of fresh air could dispel. Those days have gone and women now have more of their dresses dry-cleaned, but men continue to have all their clothes washed.

There are three which should be borne in mind by the designer and client with regard to the needs of laundry:

- as everybody is aware, the climate can be extremely hot. Even if people spend a lot of time indoors with the benefit of air-conditioning, there are always times when it is necessary to move into the heat and humidity, even if it’s just moving between building and car;

- a number of Qataris will change their clothes five times a day with prayers, and

- most men take pride in their appearance and try to appear in public in the best sartorial light.

These three issues can produce a significant amount of laundry over the day. With relatively large families the amount of laundry mounts up considerably. This produces a number of issues which must be dealt with efficiently by the household, some operational, some of them requiring programmed space:

- collecting the laundry in some systematic manner,

- storing the laundry, and

- washing it,

- drying,

- airing,

- pressing or ironing, and

- replacing it where it can be worn again.

Even for small amounts of laundry, kitchens are not the place for laundry facilities whether in the West or in the Gulf. Nor, necessarily, is a space immediately adjacent to it, both of these solutions being suggested by the proximity to people using the kitchen and the plumbing arrangements of normal houses. There are three locations which make better sense:

- on the same floor as the bedrooms and bathrooms, close to the source of the dirty clothes,

- in a basement or service area where the noise and humidity of the laundry facilities can be dealt with effectively, or

- in a separate building within the compound.

It is the women of the household who are responsible for laundering clothes, most usually, the servants of the household. Dirty laundry tends to be dropped anywhere and needs to be collected and taken to the laundry facilities. This is usually a hand-carried exercise though, where laundry chutes are provided on bedroom floors connecting to basement laundry facilities, this is relatively easy to carry out – though care has to be taken in the design of the chute in order to prevent its misuse, particularly by children.

Where there isn’t a chute, then the collection process is more difficult, made more complicated by the irregularity that dirty laundry is made available – the larger the family, the more activities in which they participate, the more spread out and irregular the operation.

The location of the laundry area will really depend upon the size of the household and, perhaps, the amount of assistance there is with the process from family or servants. The optimal location is in a building within the compound which might have a drying area associated with it. If the house has a basement with suitable space available, that might be a second best location – provided that good ventilation is provided, is not mixed with the house air-conditioning system, and extraction does not create a nuisance. If the household is relatively small then a location on the bedroom floor might be suitable preferably isolated from the bedrooms with respect to noise and vibration. In some countries the roof is a possible location for a laundry room and this might well be a suitable location in Qatar but, again, access and nuisance must be carefully considered.

The basic requirements for a laundry are as follows – omitting any process established for collecting and transmitting to the laundry, and making some safe assumptions about staffing the process:

- a dirty storage area is required where clothes can be kept prior to sorting and washing,

- top or front loading washing machines capable in size or number of dealing with general and peak washing requirements,

- a sink and draining board for hand-washing delicate material,

- a sink for soaking problem items,

- drying machines also capable in size or number of dealing with general and peak drying requirements,

- a storage area for clothes waiting to be ironed,

- an ironing press or presses designed to iron large clothes effectively,

- an area for a traditional iron and ironing board to be used for small scale work,

- a place for airing clothes that have been ironed,

- an area for hanging clothes in transit,

- a flat area for clothes, once aired, to be folded and stacked prior to their being returned to their owners’s cupboards,

- storage space for the washing and other materials required for the laundry,

- space for a sewing machine, related storage and working area for the mending of clothes and materials,

- suitable hangers and devices for holding clothes once laundered,

- equipment for moving clothes back to their storage areas,

- access to an open area for both drying and airing if necessary,

- a holding area where clothes intended to be taken to and received from external dry cleaning can be stored, and

- a good first aid facility.

One final note, that applies also to kitchens, is that horizontal working surfaces should be set at a sensible height, usually lower than those recommended for Western standards. Many of the people working in kitchens and laundries are relatively small and must be able to use the facilities easily and safely both with regard to their height and reach.

The laundry review above may seem to apply to quite a large operation, but would be scaled down for the particular requirements of a household. The purpose of this element of the notes is to remind designers that this function of a household is not catered for in the manner many of them believe. It is an area, like kitchens, that has to be discussed in some detail with the client, preferably from a basis of some knowledge and understanding.

Workmanship

One of the curious and surprising characteristics of development in the peninsula, in fact within the region, is that workmanship varies so greatly. Some of the best and worst examples of finishing can be witnessed there. The reasons for this seem to be numerous but boil down to a number of factors which, if properly considered and effected, should produce sound details and value for money.

It is a truism that the proper finishing of buildings is important to the client, the appearance of a project reflecting the money spent on it and, in turn, being a physical representation of the owners. With commercial buildings, this is how the those who move within and around them will see and judge the owners, either overtly or subconsciously; so it is surprising that poor workmanship is allowed.