a collection of notes on areas of personal interest

- Introduction

- Arabic / Islamic design

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 01

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 02

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 03

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 04

- Islamic architecture

- Islamic urban design 01

- Islamic urban design 02

- Islamic urban design 03

- Islamic urban design 04

- Islamic urban design 05

- Arabic / Islamic gardens

- Gulf architecture 01

- Gulf architecture 02

- Gulf architecture 03

- Gulf architecture 04

- Gulf architecture 05

- Gulf architecture 06

- Gulf architecture 07

- Gulf architecture 08

- Infrastructure development

- The building industry

- Environmental control

- Perception

- The household on its lot

- A new approach – conceptual

- A new approach – principles

- A new approach – details

- Al Salata al jadida

- Public housing

- Expatriate housing study

- Apartment housing

- Pressures for change

- The State’s administration

- Society 01

- Society 02

- Society 03

- Society 04

- Society 05

- Society 06

- History of the peninsula

- Geography

- Planning 01

- Planning 02

- Population

- Traditional boats

- Boat types

- Old Qatar 01

- Old Qatar 02

- Security

- Protection

- Design brief

- Design elements

- Building regulations

- Glossary

- Glossary addendum

- References

- References addendum

- Links to other sites

An introduction

The last large traditional boat to be constructed in Qatar – a boom – was built in Doha in the early nineteen-seventies. In this photograph you can see how the majority of her ribs were left more or less as the tree trunks and branches came, and only trimmed at their junctions with the planks of the boat. You can also get a feel for the size of the boat from this view of its construction. Incidentally, I don’t know if I am correct in referring to dhows as feminine in the characterisation of the West. I believe some dhows are male and some female, but I’m not sure which are which. One authority suggests that those craft with a thick and short prow are female, and those with a long and fine prow are male.

Compare the traditional craft and its construction above with this one. Both were being constructed at the same time but, whereas the first was dependent upon traditional methods of design, materials, skills and construction, this boat was a copy of a steel-hulled vessel with all its timbers being mechanically shaped to a pre-set design. This might be considered to be the turning point in the construction of wooden boats in Qatar.

This photograph shows a fleet of traditional craft with their lateen sails raised on the occasion of National Day 2009 in Doha’s West Bay. They are a beautiful sight. The traditional boats of the Gulf are obviously neither Islamic in any way nor are they elements of Gulf architecture. However, they seem to me to have so much in common with traditional Gulf architecture and the way of life prior to development irrevocably changed the life of Qataris. In this sense I see boats being as important as the traditional architecture, and I feel that they should be looked at in parallel with land-based architecture.

For this reason I have made this page in order to add a short description of what I can recall of these beautiful craft. Unfortunately, I have to warn you that I can not guarantee the absolute accuracy of everything I write. Much of it comes from conversations I have had in the past with locals with an interest in boats as well as those engaged in the construction and maintenance of them, but I regret now not making notes. I can recommend at least this article to give a description of some of the craft and their history in and around the Gulf and, for more detail of the construction of boats, particularly referring to the Kuwait ship-building industry, this site which, though it seems to have gone down when I last checked, may return, in which case I will leave the link in. More recently I have found this reference which has caused me to alter some of the notes I had previously made. The above photograph, incidentally, was taken at sunset over Doha’s old dhow jetty.

For those who have an interest in the boats of the Gulf and would like to read more about them, I’d like to recommend a far more authoritiative source which, despite its academic character, contains considerable information about the craft of the region in their context and does much to explain why the naming of craft around the Arabian peninsula is so difficult.

The first two of these three photographs are of groups of boats sitting at dawn in the low water off al-Bida prior to the Corniche road being developed in Doha. The photographs were taken in 1972 when the traditional way of beaching craft was still practised. In the first photograph there are, from the left, two small abwam, one dismasted, a shuw’i in the background, another boom and a jaliboot on the right. In the foreground is, I think, a small kitr with a second further away behind it. The low water in Doha’s bay was both a benefit in that it enabled boats to be beached easily, but it was foul smelling as it didn’t wash out well at high tide. The second photograph was taken later in the same year but also early in the morning, again showing the fishing craft waiting for high water be taken out to sea. The third photograph was taken in August 1976 and shows a mixture of traditional craft pulled up onto the side of the fill being used to create the New District of Doha, and before the edge was fully trimmed and the Corniche developed. The three photographs illustrates something of the manner in which the fishermen of Doha and al-Bida used the shallows to beach their craft when returned from the sea.

As the photographs above show, many of the local craft were drawn up onto the beach for a number of reasons. Not only was it easy to unload cargo or the fish that had been caught, but access could be made to the hulls of the craft for maintenance, although drawing the boats up to the shore was not always necessary. In al-Khor, for instance, the fishing fleet often moored in the deeper water of the khor in order to be able to move out to the fishing grounds more rapidly. Here the fleet sits out some way from the shore with the beginnings of a storm building to the north.

The third of this group of photographs shows a single boat lying on the sea bed at low tide off al-Bida. The old Diwan al-Amiri can be seen in the background, and the beginning of the Corniche construction had just begun. The boats were a common sight in the 1970s with their crews wandering across the sea beds in carrying out their maintenance. The boats and their associated activities created a strong link between the past and present which development of the Corniche cut off.

The increase in revenue from oil in the Arabian/Persian Gulf has seen a considerable increase in the use of modern shipping. This reflects the larger size and frequency of ships needed to bring goods into the different countries of the Gulf, in turn a response to increasing disposable income, the rapidly expanding population and concomitant development. Bear in mind that the national populations of the Gulf have been significantly increased by the service population brought in to carry out the considerable development politically considered necessary to bring those countries into line with the more developed countries of the West and, of course, the region.

This growth in Qatar has been dramatic. At the beginning of the boom in the seventies, for instance, ships would often have to stand out in the roads to wait their turn to unload while, on land, intense efforts were being made to upgrade the unloading capability of the ports, road and commercial and government infrastructures in order to feed the goods into the country. I should add that it was only the east side of the peninsula that was able to take deep draught vessels and even then the ports of Doha and Umm Said had to have channels dredged. Doha was the commercial port, Umm Said reserved for the export of oil.

Prior to this, goods were moved within and out of the Gulf by traditional wooden craft. These boats relied on their large lateen sails though, later, diesel engines were added to the dhows both in order to improve their manoeuvrability near land as well as to enable them to sail when the winds dropped. Even today these craft ply their trade between the Gulf and the Indian sub-continent and east Africa via the Arab states on the Arabian Sea. The dhows still use sail when it suits them, though this is obviously dependent upon the prevailing seasonal winds. I can recall often seeing them drop their sails out in the roads and use their diesel engines to manoeuvre into harbour. The diagram illustrates not only the changeability of the winds, but it also reflects the dominance of the north-north west shamal within the Gulf. It also illustrates the dominance of Oman between the two bodies of the Gulf and the Red Sea.

But first a little history…

For thousands of years the sea has been one of the main systems over which trade has been carried and communications effected. There are, of course, land routes for the further distribution of goods and for communicating, but the sea was open and, in significant ways, free of many of the obstructions to movement, trade and commerce found on land. Initially, movement by sea would have been close to the shore. This enabled sailors to navigate easily on land bearings as well as to sail through relatively safe seas while obtaining rapid access to a safe haven in the event of a storm. Over time the improvements in maritime technologies together with better understanding and familiarisation with environmental conditions led to sea routes moving further away from land with, eventually, major sea and cross-ocean journeys being undertaken.

The people who made these journeys were brave, for the sea can be capricious and dangerous. But it has a beauty which sailors recognise and which draws them to it not just in the pursuit of trade but in a separation from their life on land. This draws them together as a group of like-minded individuals who have to work to a common purpose in order to be able to carry out their work in relative safety. The bonds formed between sailors were, and to some extent remain, regardless of nationality. For example, it is only a relatively short time ago that the people of England were concerned that their compatriots in Kent might side with the French due to their maritime links across the Channel. It’s possible, of course, that the French might have had similar fears about their Normandy and Picardy sailors siding with the English.

The history of sailing craft in the Gulf is not necessarily one that derives from the countries or people bounding it, for some of the influences come from farther afield. It appears that the chief influences are from Persia, the Indian sub-continent and the Portuguese, then from British naval craft. It is probable that there is much to learn from the influence of the Chinese who, for centuries, were the most advanced in their use of craft, navigational aids and marine technologies. Due to internal problems, the wide-ranging activites of the Chinese fleets stopped in the fifteenth century. Although there has been some investigation into this element of Chinese history, not much is yet known in the West of these craft, the science and technologies behind them, and their influence on craft, navigation and marine sciences in the Indian Ocean and Gulf.

It is from Persian, Sanskrit and Akkadian sources that much of the information learned today has been discovered, and this process is continiung. There are, however, difficulties in sourcing information due to a number of factors as

- some sources are difficult to read and understand,

- the extent to which writers understood their subjects is hard to determine, and

- graphic sources, while valuable, are difficult to assess in relation to their relevance and accuracy. They provide clues but not answers.

There would have been many influences from around the region, but the Portuguese caravel and the Ottoman oared fighting craft would have have had a consequence on local craft as might the British ships seen in the region in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The caravel was designed as a light, manoeuverable craft suited to long distance travel but needing supplying on long journeys. Characterised by two or three lateen sails it developed from the thirteenth century in and around the Mediterranean to become a larger and more effective ship used by both the Portuguese and Spanish navies, the lateen sail later developing into a square sail. Originally developed as fishing boats, when used as warships, caravels depended on the stern castles as fighting platforms.

The Ottoman oared galleys were a very different type of craft. Powered by oars they were fighting ships but obviously did not have the range of a caravel, though they were also fast and highly manoeuverable. Their main armament was their heavily reinforced prow which was designed for ramming.

British war ships moved into the Gulf and Indian Ocean in their work of protecting the trade routes to the Indian sub-continent. Brigantines and cutters would have been common in the region. The larger ships did not have the shallow draught needed to manoeuvre in-shore, a job left to smaller craft, particularly oared. Efforts by the British to contain or defeat piracy in the Gulf were particularly constrained by this factor. But at least it introduced these new craft into the Gulf where their effectiveness in different conditions would have been noted and learned from by local boat builders.

It is probable that all these types of craft influenced marine technologies in the region, one relating to commerce and travel, the other to war. Nevertheless, it appears that it was the Persian influence that predominated from India to the southern point of Africa. Clues to this lie in many areas of research and study such as:

- textual,

- historical

- maritime,

- navigational,

- lexicographic,

- archaeological, and

- iconographic,

much of this relating to nautical theory and practice, shipping and trade within and across the region. But it has to be borne in mind that primary sources provide us with little assessment of the importance of trade, nor can we be certain of the extent of knowledge of medieval writers in relation to technologies, material and the like.

What we can be certain of is that cultural and commercial exchanges developed along sea routes, and that boat building developed in response to the need for local and long distant travel to improve.

While reed craft were common in Egypt and Mesepotamia, there was little development of this type within the region. Although they were inexpensive to build and maintain, they had limited carrying power and would only have been safe on rivers or inshore waters. As you might expect, sailing craft which developed within the region were designed for the work they had to perform and, particularly, the waters in which they would sail. Reed craft are more suited to rivers and inshore sailing and so wooden craft developed relatively quickly in order to provide safer movement across greater distances.

Initially wooden craft were constructed from planks, butted and sewn together with ribs added after the planks had been joined. This photograph shows how important the junctions between planks must have been to the integrity of the craft. This type of construction will have relied upon good craftsmanship by the boat builders, requiring accuracy in the cutting of the planks and in the making of holes for sewing the planks together. I am not able to say what material might have been used for caulking, placed by a qalaaf, between the planks and in the holes but I believe that it would have been a fibrous material, fatail, capable of holding a substance such as fish oil, sull, as is used nowadays, to repel the ingress of sea water. As can be seen in the photograph, the planks are held with a cross stitch using a material such as leather or a suitable natural material, perhaps a root or a coir or coconut rope.

In an update to the previous paragraph I have learned that the replica of a ninth century Arab ship, the Jewl of Muscat, constructed in the Oman in 2008, had the holes in its planks made watertight by hammering in coconut fibre which was then made watertight with a putty, shawna, made of chalk powder (calcium carbonate) mixed with melted khundrus resin and fish oil. Also, that the sails were made in Zanzibar from woven palm. I understand from the Director of the Jewel of Muscat project that putty, made with lime (calcium hydroxide) and animal fat heavily pounded together, was used in the construction of Tim Severin’s sewn boat, the ‘Sohar’ in 1980. The material stayed pliable for a few days but eventually hardened, a difficulty where there is movement that must be accommodated.

In the early days of boat construction, there would have been neither the technology nor materials to use nails in their construction. Interestingly it is said that one of the reasons nails were disliked in the construction of boats was that it was considered they might be drawn out by magnetic forces below the waterline. It is far more likely that nails were initially avoided due to their tendency to be affected by the marine environment. Despite this, it was not uncommon for nails to be used to fix planks at the prow and stern where the two sides of the craft became extremely close together, and the ability to work the fixings inside the craft was too constrained.

One other point that I find interesting is that boats were considered to have similarities with camels. It is well enough known that camels were sometimes known as ships of the desert, but their long necks and the masts of ships were also compared both for their forward-leaning appearance as well as the sinuous movement while travelling. Here there is comparison with another part of the world. Researchers who have sailed replicas of Viking longships of northern Europe – craft whose planks are also lashed together – have commented on the twisting movement of the longship through heavy seas. This movement, they say, is very suggestive of a live animal and suggests this as being the reason that the prows of Viking longships was cusomarily carved in the form of a figurative, dragon’s head which also had a talismanic character to it. But I digress…

For millennia sailors have used the seaways for the movement of goods and the winning of resources. The Gulf appears to be a safe place for shipping, but this can be illusory; the Gulf is large enough for even the larger craft to be at risk from adverse weather conditions. But most of the time the weather is good, and those who put out to sea can relax in the knowledge that they have the skills to carry out their tasks in safety. This photograph, of a captain at the helm of his small shuw’i, represents this understanding and illustrates the innate ability sailors have to steer their craft in a natural and instinctive manner while carrying on the business of the trip and conversing with those around them.

The dhow

The name commonly given to an Arabic boat is dhow, although Arabs more commonly refer to them collectively as khashab. Here, under unusual light conditions, one sits at anchor in Doha Bay off the old jetty in 1972. But, just as the names ‘ship’ and ‘boat’ in English are commonly used to encompass a wide range of different craft – yacht, punt, canoe, launch, ferry, freighter, liner and so on – there are a number of traditional Arabic craft found and still used in the Arabian/Persian Gulf and retaining their traditional names. These names do differ in different parts of the region, as do the shapes of the craft.

The origin of the name dhow is still argued over today. One story I was told is that its real origin was in one of the Arabic words for a lamp or light. Supposedly a British sailor asked a local for the name of ‘that over there’, pointing at a boat with a lit lantern, and was told dhow, the Arab thinking the sailor was asking about the most obvious thing to be seen in the dark, the lamp. Like most apocryphal stories it’s unlikely, but I still like the story.

The etymology of many of the terms has much to do with the wide area over which the boats roamed for centuries. Indo-Persian mixed with African and Arabic vocabularies and, as much of the traditions were not written down but verbal, attempting to discover roots and meanings can be difficult, and I am neither an etymologist nor linguist.

Dhows come in a variety of shapes and sizes developed, as in other areas of the world, in response to the boats’ purposes and the character of the seas in which they sailed. Dhows which sailed across the Gulf were often subject to violent seas, and this is particularly true for those moving out of the Gulf and across the larger Arabian and Indian seas. This view of a shuw’i is typical of the most common boat now used, leaving and returning every day from fishing with their traps on the stern.

At the same time it should be borne in mind that many of the waters of the Gulf are very shallow. This is something the British found to their cost when they attempted to settle what was known in the eighteenth century as the Trucial Coast, in which there was endemic piracy. The well-armed, but heavier British ships, were unable to follow pirate ships which, with their lateen sails and shallower draught were easily able to out-manoeuvre the British. Here, one of the local craft has been fitted with a lateen sail and moves across Doha Bay.

The lateen sail has a particular advantage. Its fore-and-aft rig can be used to sail closer to the wind than the square-rigs used by European craft. They were smaller sails than the equivalent European craft but, with their long keel, shallower draught and lighter weight these craft tended to be faster. This combined with easier manoeuverability and their sailors’ local marine knowledge, gave them significant advantages.

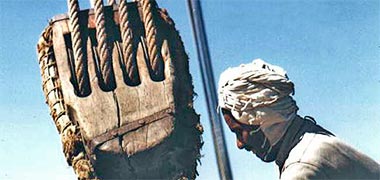

The first of these three photograph is a detail of a single block of halyard sheaves, part of the rigging of a dhow. The raising and lowering of sails is a heavy business and requires all the aid possible in order to accomplish these two acts quickly and efficiently. Setting the sail to the correct height and manoeuvering it around the mast are important functions that place or set the sail to the requirements of the master of the vessel. The sheaves enable the effort being made in pulling the halyard lines or ropes to be more efficiently managed, and were an important development in the rigging of sailing craft. A pulley system such as contained in this block will, theoretically, enable the effort put into hoisting to be improved by a factor of eight – less friction. Note that this block is made of a hard wood and appears to have metal sheaves or pulley wheels within it. Externally it is bound with both hemp rope and metal in order to retain its strength against the strong loads that act upon it. It’s probable that the metal band was added when the block began to split. The second photograph shows another block of sheaves at the head of the mast, the reciprocal of that in the first photograph.

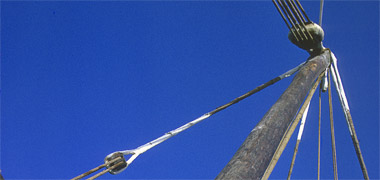

This upper halyard block was photographed on a different traditional craft from the previous photograph, and with forty-five years separating them. It is placed here to illustrate the relatively crude but effective design and construction of these blocks. Carved from a single piece of hard timber, this block has not yet had to be strengthened to prevent its splitting, despite the heavy loading it takes in operation. The favoured timber for blocks is Jack wood, Artocarpus heterophyllus, locally known as fanas and obtained, as is much of the timber for building these craft, from the Indian sub-continent.

Nowadays it is rare to see lateen sails in the Gulf other than associated with tourism or government-sponsored touristic events. However I can remember that it was not uncommon to see the sails on the horizon where their captains would use wind power out at sea for the major part of the journey, but lower their sails and use their diesel engines to manoeuvre into harbour.

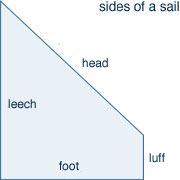

The notable characteristic of a lateen sail, as you can see from this photograph, is that it is triangular, the leech or trailing edge being extended to optimise the amount of wind it can catch. You can also see how the sail is extended fore and aft to increase the amount of wind caught. Apparently it developed from a square sail as the need to head up closer to the wind was seen to be important. In fact a lateen sail can sail closer to the wind by at least a point – 1/32nd of the compass 360°, or 11¼° – allowing them to sail at least within four points of the wind compared with a square sail achieving only five points. It should also be borne in mind that lateen sails were not designed to be reefed in strong winds as were, for instance, the sails of Chinese junks. In order to deal with stronger winds, smaller sails were usually carried.

I’ve not been able to talk to any Arab sailors about the lateen sail but was interested to read that dhows were often sailed into the wind and would wear around rather than tack. Tacking brings the bow of the craft across the wind and requires both that the yard is brought round the mast and that the rudder is effective in the manoeuvre. Wearing also requires the yard to be brought round the mast, but turning downwind helps move the yard around. With the relatively small rudders of Arab craft, wearing would have been a more easy option in heavy winds.

‘Tacking’ a boat has the craft heading into the wind and zig-zagging across it as the craft beats its way forward. ‘Wearing’ has the boat making figures-of-eight. Heading into the wind the craft, instead of tacking across it, turns away from the wind and then rounds up to head up again into the wind. It is a lengthier procedure, but easier to accomplish in strong winds.

Interestingly, the experience of the Arab sailors on having to deal with the heavier-armed British warships resulted in a change in construction. Their boats were traditionally made with teak planks connected with coir rope bindings and heavily greased. This had given them literally flexible craft, better suited to dealing with the sandbanks and reefs of the Gulf. The nailed oak planks of the British navy were emulated and dhow boat construction developed using wrought iron nails driven through bow-drilled holes packed with hemp soaked in an oil and tar mix.

The types of boat were characterised by the functions for which they were developed. Unlike Western boats, they were not differentiated by the number of masts but by their shape and size.

All dhows are traditionally powered by the wind driving a lateen sail, a triangular sail hanging from the mast at an angle, and permitting rapid deployment about the mast and enabling the dhow to sail closer to the wind than their contemporary British ships.

The three main uses for dhows in the Gulf were in the:

- pearling industry,

- the movement of goods around the Gulf and, in and out of the Gulf, linking with the Indian sub-continent, East Africa, the Red Sea and

- fishing,

the latter two being the only two uses left – though to which must now be added

- recreation.

Having said that you should be aware that, in contradistinction to the way in which boats tend to be classified in the West, boats in the Gulf were used for whatever function was required at the time. Essentially this was a commercial necessity, the owners finding work for their boats depending on opportunity. What I’ve not been able to work out is how the different boats came to be sized and constructed into the standard models described below. I assume that it is, as it would be elsewhere, a result of the characteristics of the seas they sailed, from the coasts of the Arabian Sea to the calmer inshore waters of the Gulf.

Pearling

This photograph is of a pearling boat, taken on one of the National Days in the early 1970s and is thought to give a reasonable indication of the way the craft would have been dressed and manned. These craft stood over the pearl beds for months at a time, the crews’ only protection the canvas awnings spread over the main deck as shown here. Manoeuvring was carried out with the oars, with as much time as possible given to diving and winning the oysters from the sea bed.

These two photographs were found in the suq and illustrate a little of the activity on pearling craft. It was a hard life, under harsh conditions but was one which appears to be regarded wistfully by those who were involved in it. While visitors to the Gulf are now able to see the fishing fleets in action and perhaps take advantage of the recreational craft operating as businesses, most will also be aware of something of the history of the pearling fleets on which the original wealth of Qatar was largely founded. Although the industry was crippled by the development of cultured pearls in the Far East, there are not only the tawwash, pearl dealers and divers alive who participated in pearling in the Gulf, but even some who occasionally dive, recreationally, for pearls. To the merchants pearls are not only items of intrinsic value, but they each have memories associated with their finding. It is fascinating to see a merchant take out the rolls in which he keeps pearls and fondle them as he recalls and recounts their individual histories. From the point of view of this page of the notes, the most important point to bear in mind is that the boats were not only wind powered, but rowed by their crew as can be seen above.

This model of a pearling dhow shows some of the equipment which is used by the divers. The most notable features are the weights, khir, used by the divers to help them reach the sea bed, and the dayin, cotton rope baskets, used to carry the oysters to the surface. Usually the khir would be stones, hasa, though I have seen it written that sometimes metal was used for this purpose as seems to be indicated by the model. More notes on pearling can be found on one of the Society pages.

Fishing

As mentioned earlier, the other main use for traditional boats was fishing. Fishing fleets were established all the way around the coast with a small settlement supported by, and supporting, the boats and their crews. Most of the settlements were located immediately next to the sea, with only a small stretch of sand separating them from the water. This was the case at Doha and Bida as well as at Wakra. The boats would be pulled up onto the sand, rather than being left in the water, and the nets were stored and mended along the beach and outside the houses of the fishermen. The top photograph, although taken recently at Wakra, shows something of the character of these villages as they would have appeared in the past with their boats drawn up along the beach. The lower photograph was taken in early 1972 and shows how little has changed – though I notice that the architectural treatment of the nearest building has been amended. There is also evidence of the stagnation caused by the sand bar that gradually moved south to restrict sea access to the foreshore.

The conditions for drawing up boats was not always perfect, some of the fishing villages were protected by coral reefs of sand spits, limiting access, though providing a degree of protection to those living in them. In many of the coastal communities boats were either left in the water, as in the second of these three photographs taken at al-Bida in 1972, or drawn up close to the shore, as in the lowest photograph which was taken at al-Khor in the same year. In the latter case the khor provided considerable protection to the village and, by extension, the fishing fleet here sitting out a hundred metres from the shore.

But these were not the only fishing operations in the peninsula. In many different locations, small communities established themselves in temporary barasti accommodation in order to take advantage of the good fishing that was to be enjoyed at that part of the coast. This photograph was taken near Umm Said and shows a typical group of huts with the nets stacked near the huts, small rowing boats drawn up on the foreshore, a truck for access to markets and the important galvanised iron water tank storing fresh water for the fishermen̵s personal needs.

While the various villages were provided with fish by their own fleets, there was also markets to be addressed elsewhere in the peninsula. The main market for fish was in Doha, the largest conurbation. Originally fish was sold along the shore directly from the boats all over the peninsula. However, in the nineteen sixties, the government constructed a purpose-built structure in Doha just north and east of suq Waqf for the purpose of selling fish. Here the catches were brought in and sold with small boys carrying out some of the preparation for customers, such as gutting fish and peeling prawns.

But at the other end of the scale, fishermen operating along the shore such as those camping in temporary huts, such as those in the photograph above, would sell fish directly to Qataris camping along the shore, as is shown in this photograph, taken in 1976. In the background you can see a fishing trap installation which is likely to have been the source of the catch. They would also be able to provide fish for any badu living in the vicinity.

Doha continued to have a large fleet of boats engaged in fishing, though my impression is that it was not the largest fleet, that being at al-Khor. The impression may be wrong as the foreshore in Doha along both its east and west bays was long, and there were considerable number of boats engaged in transportation mixing with them, particularly opposite the north end of suq Waqf. Here it was a common sight to see the different nets of the fishermen hung over the railings or stretched out on the ground to inspect, mend and dry.

The continual use of nets together with the sharp corals to be found at sea, creates continual damage to the fishermen’s nets. One of the most common sights along the foreshore was of fishermen sitting and mending their nets. Constructed of polyester twine and brightly coloured, usually in tones of green and blue, the nets had to be mended daily in order to be ready for the next trip.

Similarly, here at al-Shamal, is a familiar sight around the eastern and northern coasts of the peninsula, fishing nets carefully stacked with their polystyrene floats waiting to be loaded and taken to sea. Note the typical colours of the superstructure, mast and spar of the moored fishing craft, as well as the fact that many of the fishermen are now expatriates and not nationals. Fishing is still a sport or hobby carried out by Qataris, but the majority of those fishing as a business are not, most originating from the Indian sub-continent.

Fishing with nets was not the only way of catching fish. There was a small amount of line fishing carried out from shore, usually by individuals wishing to feed their family rather than for sport. Yet this was not the only method used by those without access to boats. Here a fisherman uses a casting net from the shore at feriq al-Salata, his catch-box carried over his shoulder in which to keep the small fish caught in this activity. It may not have caught large fish, but there always seemed to be a lot of smaller ones visible in the shallows.

It is likely that the first form of fishing in the region was the passive use of fish traps. In the first photograph you can see the general principle photographed from the air. In the shallow waters, a line of hasa or, more likely, faruwsh was constructed which would be exposed at low tide, but covered at high tide. Fish, moving around the shallows near the shore, would find their way back to deeper water barred by the trap and could be relatively easily caught.

The development of this form of passive catching was the fish cage. This system has the advantage over the system illustrated above in that it is extremely portable, allowing the fishermen to carry the cages to specific areas of the sea where they know fish will be found. These first three photographs, all of them taken in the nineteen-seventies, show traps under construction. The first photograph shows a trap being woven upside down, the weaver standing inside and moving around in order to keep the shape symmetrical. In the second photograph, the rolled up semi-completed cages can be seen stock-piled prior to their bases being attached. The third photograph, below, is a detail showing the bases being attached in order to complete this cage’s construction.

These woven, steel wire cages were taken out to sea and left on the sea bed for fish to find their way into, and from which they would find it difficult to leave through the small funnel via which they gained access to the cage. One of the photographs above shows a shuw’i, laden with fish traps, leaving Doha to set them down, though some of the traps were set near the shore, either carried out manually or on small boats.

It was common for fishermen to set their traps by moving them directly into the sea at low tide as is shown in the lower photograph. Here two fishermen are carrying out one of their traps from where they kept them on the island of Safliyah, just north of Doha, among people enjoying their picnics and swimming on a holiday. It must be difficult for the fishermen, but I assume the fish return after the people have left.

Freighting

While pearling and fishing have been traditional functions of country craft, the larger vessels, such as the boom, have been involved for centuries in carrying freight across and along both sides of the Gulf littoral and as far as the Indian sub-continent and the east coast of Africa, as noted above. This trade was an essential activity, moving a wide range of goods mostly into the Gulf states. In this photograph, taken in the early 1970s on the dhow jetty at Doha, building supplies are being carried ashore down an improvised gangplank.

But time brings changes and while there is still the necessity to move freight, the traditional craft have changed in a variety of ways. This photograph is of a Pakistani boom that has been modified to carry freight, in this case, livestock. The superstructure at the stern is a modern version of the older structures though has been painted to give some resemblance to a more modern, steel, freighter. Yet there is still a zuli hanging from the stern. Curiously, the stem piece has been cut down and even appears to have a forward crank in its leading edge. The mast has no sailing function but is rigged as a derrick for handling purposes.

Recreation

Qataris enjoy the sea now as they always have. My experience is that it is not only those with a marine connection that do so, but also those of badu stock. Because of this, recreation is an increasing activity in the use of smaller, less expensive, dhow s in Qatar. This reflects both a decrease in the traditional use of the dhow – pearling and, to a smaller extent, fishing – and a significant increase in disposable income and time available for recreation. Those who can afford it can usually afford to employ somebody to look after and helm the boat when it is taken to sea, and the boats are usually available at short notice.

Increasingly, many traditional boats are being turned into leisure craft, their owners no longer having use for them as working boats. This boat was converted around the late nineteen-seventies from its original use, and provided with a cabin created aft which had two windows set into the stern transom to give light and ventilation. Curiously, the type of divisioning selected for the fenestration gives it the feeling of some of the Western sailing ships from earlier days.

Here is a more modern example of the stern treatment of a traditional craft, a shuw’i designed, obviously, for recreation rather than as a working craft. There are a number of points of interest here. First, the strakes projecting back from traditional and modern working craft are here residual, having lost their function of supporting a structure on the stern. It is unclear to me if the four panels on the stern are just panels or, as seems more likely, small windows set in to illuminate a below-deck cabin. There is considerable decorative naturalistic carving enlivening the hull and columns supporting the stern shade structure. More dramatically, blue and white diagonal painting has been introduced to pick out horizontal elements of the hull. It is not clear to me what function the three painted bands forward of the stern represent.

This photograph of a dhow illustrates a typical converted leisure craft at its mooring. You can see that a considerable amount of the available deck space has been enclosed and glazed, that above this a deck has been created with seating established on it, and that modern navigation and communication systems have been installed as well as two air-conditioning units.

Many such dhow s have been converted for recreational use by their owners, and the market for them has risen accordingly as those who have not been in the marine business have sought out these craft now they have the funds to afford them.

Generally the interiors of these craft are enlarged and enclosed with the addition of facilities such as air-conditioning and television being made. Fishing is very popular from them and day trips are common both for men and their guests as well as for all the family.

With increasing leisure time, sometimes the trips take place over a number of days and, in a similar manner to camping in the desert, sometimes the owner will travel to the boat – or vice versa – each day. There seems to be a genuine interest in the sea both by those you would expect to have this love of the sea – those whose families have been associated with fishing and pearling – as well as those whose families come from the desert. In both cases it often appears to be very much a relocation of the majlis from the land to the sea, and with similar activities undertaken. Nevertheless fishing is very popular activity and everybody seems to come back from their trips with fish for the table, friends and family, as well as for the freezer.

The boats used for recreation can consume considerable funds as not only do the boats need maintaining, but they invariably have at least one crewman to handle everything to do with maintaining and running it. Generally boats are looked after well. It is apparent that while the interiors may be unsophisticated, the basic elements of the traditional craft are detailed, well maintained and, in cases such as the zuli developed from both a functional and decorative point of view.

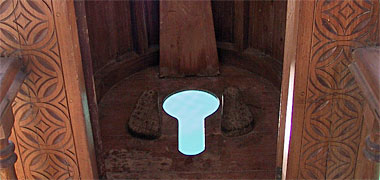

In addition, the opportunity is taken to add details which would not have been used traditionally on dhows, but which find their provenance in the traditional Gulf architecture of Qatar. In the case of this solid, carved detail, it illustrates both the relationship between owner and boat as well as that with his heritage.

The boats above have been relatively tastefully converted and retain a lot of their original character despite the addition of enclosures and the provision of air-conditioning. The main reason for this has been in maintaining a recognisable shape of the craft, and keeping them honest to their purpose. Here are three boats which are slightly different.

The first of the two is a shuw’i which has been given a modern styling. The curious thing is that it appears to me not to be constructed of teak but perhaps of steel or fibreglass, though I have to admit I’m not sure. The clues are the openings in the hull, its unnatural smoothness and the fins at water level on its stern. The addition of the two zuli over the stern give it an interesting symmetry and the detailing of the cabin is certainly modern. Without a doubt it is an attractive craft and, if I am right about the construction, I have no difficulty with the copying of a traditional form in a different material. If you compare this with comments I have made about pastiche in traditional building, then I think this is a reasonable and well executed way of designing modern boats.

Here, however, is something rather different. The craft in this photograph appears, again, to be a converted shuw’i, here constructed in the traditional manner, but on which has been constructed a rather unsympathetic addition. If you compare this with the photo of the converted shuw’iabove you will see a significant difference. The shuw’i further up the page has its cabin positioned so that it is possible to move around its external wall in order to reach the stern. In this shuw’i the cabin has been constructed as an extension of the hull – you can see the shape of the traditional stern extensions enclosed by the cabin wall in this photo – but this key element of the form of the shuw’i has been masked by the cabin walls which have been extended even further than the traditional extensions. While both craft have square windows, those on this shuw’i look cruder as they are not masked by the extended cabin roof. These decisions have, to my mind, compromised the design of the traditional shuw’i and, while times change, this really is not an attractive addition to the marine fleet.

This shuw’i has been converted slightly differently from the craft illustrated above, in that the extension to the stern has been carried out in a way that preserves the visual importance of the stern strake extensions. Despite this, however, the mass of the new cabin seems out of character with the lines and volume of the shuw’i and produces an ugly design from what is basically a beautiful craft. Under normal conditions, when design development begins – in this case the conversion of traditional fishing craft to recreational use – there are likely to be anomalies as immediate needs can take precedence over form generated over centuries. What is surprising to me is that boat builders have not yet begun to find forms more in tune with the design of traditional craft, and produce results where land-based architectural forms are applied in an uncoordinated manner to a marine-based architecture.

Here is a photograph of a similar shuw’i putting out from Doha’s harbour. The reason I have included it is to show a little of the differences that exist with converted shwa’i. A small, but enclosed zuli has been added over the stern between the transom strakes, and a platform sits across the stern directly above the zuli, but smaller than the structure in the shuw’i above. As a consequence, this will produce a more stable craft if the intent is for passengers to use it, and it is not provided just for the use of the captain or members of his crew, as is the custom.

Boat building

The construction of craft in the traditional manner ceased by the nineteen-seventies in Qatar. Many years before this, perhaps centuries before, these craft were no longer bound together but nailed for the reasons given above. But, by that time the method of sourcing timbers used in boat construction had also changed and I have never seen nor heard of un-planed timbers being used in their construction since then.

These two details of boat construction were taken in the main hull and the prow respectively of the last boat I saw being constructed in Doha, in the mid-seventies. The wrought iron nails in the upper photograph were being used to make temporary fixings to elements of the construction. The lower photograph gives an indication of the tight space formed between the keel and the planking at the prow which is also a possible reason for a preference for nailing over stitching at these tight points.

Note that the wrought iron nails are heavily flat-headed unlike the wrought iron nails used on traditional doors which are hollow dome-headed for the effect they create. The flat-headed nails are driven into the timbers and countersunk to produce as near a flush finish as is practicable.

The construction of these boats is still carried out without benefit of drawings and relies on the master builder and his experience for direction and supervision, a general brief for performance requirements having first been established with the owner. While boat builders all have to be extremely skilful in their work, the traditional craft of three-dimensional shaping of wood seemed to be more so in those days. Here a craftsman sits in the hull of the boat, using an adze to shape a rib to fit snugly against the planking of the boat.

While cutting tools are used to shape the planking and ribs of boats, bow drills are needed to produce the holes through which the nails are hammered to fix the planking to the ribs, and a cold chisel to hammer caulking between the planks to make them watertight. Here is a set of tools belonging to one of the craftsmen on an adjacent boat nearing completion. Each of the bow drills has a diamond shaped point of a different size to produce the range of holes needed for different fixing requirements.

Here you see a bow drill being used by a boat builder in preparation for fixing the wrought iron nails through the planks of the newly constructed boom seen in the photograph at the top of this page, and into its ribs. This operation is extremely skilled even though it might be thought old-fashioned. The drill consists of a handle in which the end of the steel drill bit is allowed to turn, and a secondary wooden bobbin attached to the drill bit which is turned backwards and forwards with the aid of a wooden bow supporting a thick cord wrapped round the bobbin. Tension on the bow drill is maintained by the fingers of the hand holding the bow. The sharpened, diamond-shaped bit on the drill is remarkably effective in the right hands, the bow drill giving substantial control to the operator and allowing slow or relatively fast speeds to be used when drilling. High speeds have to be avoided as they tend to burn the wood.

But times have changed. While some traditional tools are still used in carpentry in general and boat building in particular, many new tools have been brought in to help speed the process of building. Here you see two electric drills being used for a similar task as that being carried out in the photo above it where a bow drill is being used – the provision of holes into which nails are being driven to hold the planking to the timber frame.

Having drilled a series of holes in the planking to accommodate the nails – whether by the traditional bow drill method or the modern electric drill – the wrought iron nails are hammered into the holes. The nails are manufactured with a square cross section and the holes, obviously, are circular and sized to be a tight fit for the nails. The square section helps the nails maintain a good bite on the timber, resisting turning and loosening as the planking and frame of the craft move in response to the pressures exerted on them by the sea and wind.

Dhows were constructed originally with the planks fixed together side by side working up from the keel, itself preferably a single piece of timber. Ribs were then inserted to strengthen the planking. Nowadays construction has the ribs constructed first and the planking added.

This photograph is of the finished construction on the interior of a small craft and illustrates a number of points. If you compare it with the photograph at the head of the page you will see the difference between old and new constructions in the irregularity and regularity of the two constructions respectively. This photograph reflects the use of standardised material in terms of timber dimensions, and is considered to improve the speed of construction as well as produce a better balanced craft. The other thing to notice is that each horizontal timber has the ends of the nails connecting the planking to the ribs turned over to prevent their working out. With traditional nails, which were made from wrought iron, this produced an extremely strong fixing, one which was very difficult to work loose.

As I mentioned previously, small craft originally were constructed of teak planks held in place by greased coir rope bindings, creating a flexible construction. One of the difficulties of this form of construction is in making the fixings within the increasingly narrow space at the prow and stern of these craft. This space can be imagined from the above photograph. Using nails driven in from the outside of the craft significantly simplified this problem.

Compare this photograph with the first photo at the head of the page, and the photograph below. This is not a boom under construction, but a general purpose cargo vessel, the photograph having been taken in the late nineteen-seventies. Perhaps this was one of the first modern boats to have been constructed in Doha. All craft are still constructed under the supervision of the master boatwright using the same craftsmen, and generally without drawings, but the tools, equipment and materials used have changed significantly enabling, perhaps, more precision but, particularly, enabling the construction to be effected within a shorter period of time. Where the craft are being built for recreation, more time is needed to provide the higher standards of finish and equipment that recreational staff require.

The construction of boats nowadays continues with the advantages that modern technologies can bring. The planks that form the sides of the craft are usually cut by band saw and will bear the typical marks that are displayed as parallel bands running at right angles to the length of the plank, typically at about 50-60mm centres. The ribs of the boat are cut and temporarily fixed as is illustrated in the photograph above, and then the planks or strakes are attached as is illustrated in this photograph, the planks being shaped and fitted by eye. Here you see the stern of the shuw’i with the strakes projecting, as yet untrimmed. The projecting strakes that are characteristic of the stern of the shuw’i have yet to be fitted. The stem post on which the rudder will be attached is in place, and provision has been made to take the propellor, forward of the post below the waterline.

Here, at the prow, most of the strakes have been added and the ends of the ribs are still projecting, as yet untrimmed. The top strake, the sheer strake, has been fitted. On the left of the photograph it is clear that strakes have not been fixed more or less parallel to each other, but have been trimmed to fit. This is a key part of the craft of the boat builder. A pair of anchor bitts can be seen standing each side of the prow to which mooring ropes or anchors can be attached for mooring or anchorage.

In the water this shuw’i is riding relatively high as can be seen from the caulking at the waterline. The pattern of fixing nails is clearly seen, an important aesthetic consideration in the new craft, but one that diminishes as the visual appearance of the nails age with time and exposure. One particular effect to note here is the added protection that has been given both to the front of the prow as well as to the sheer strake. I’m not sure what material has been used to effect this, but assume it to be iron or steel, the former preferable.

These next three photographs are of shuw’i in the harbour at Doha. They are here to illustrate how some of the wooden craft are being decorated. There appear to be two reasons for this. The first is that there has been a tradition in the Indian sub-continent to decorate their wooden craft, and many of the builders of wooden craft in Doha have been brought in from that part of the world. In fact they populate the boatyards the length of the Gulf. As with any industry there are those who specialise in different elements of the manufacture of these craft; some build, some decorate and, in the suq there is even a model boat builder brought in produce models for the tourism industry.

The second reason for decoration must have something to so with the amount of disposable income there is available for these, now recreational, craft. While the lines of boats have an intrinsic beauty in them related to the functions they have been designed over time to fulfill, the urge to decorate lies within all of us. There are parts of the craft that cry out to be decorated and, in these three photographs you can see how this has typically been carried out.

The three photographs show how the prow, stern strake and sheer strake have been decorated. It is evident that the carvings have no relationship with traditional patterns found in Qatar, but it has to be remembered that, in a sense, the craft belong not to Qatar but to the traditions of the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea. One particular difference between these craft and the older, traditional shuw’i is the shape of the prow in the first photograph where it can be seen to have little of the strong reflex curve of the traditional country craft.

While the carving on the prow, stern and sheer strakes are strongly curvilinear, the door panels in the lowest photograph show a far stricter geometric pattern. I don’t know why this is but suspect that part of the carving was carried out by craftsmen from the Indian sub-continent, while the doors have been decorated by a local craftsman. What is noticeable is that all the carving is carried out within framed panels; there is no carving in the round.

Here is a fine example of the neem of a shuw’i. This forms a roof over a part of the poop deck of some country craft. Its elevated position is commonly used by the master of the vessel both during the day and night. From here he is able to monitor not only the deck and activities of the crew, but also the surrounding sea and sky. This example has turned wooden balustrades alternating with metal rods, and there are also carved rosettes decorating its edges.

Contrast the neem of the shuw’i above with this neem on a working shuw’i photographed in the early 1980s in Doha’s country craft harbour. This is the more usual type of arrangement showing only the functional requirements for elevating the neem to a suitable position where it can be seen to contain a folded mattress and, hanging from the stern, the white polystyrene buoys commonly used by fishermen to mark their nets or traps. Compared with the more sophisticated example above, this neem does not have a built up edge to help contain anything placed on it from rolling off in bad weather, or when tacking heels the craft.

Steering

Some of the country craft that are sailed nowadays use the type of rudder with which we are familiar with on small craft in the West, a rudder attached to a vertical post, hinged to a stern or stern post, and operated by a tiller attached to the rudder head as illustrated in the photograph above above.

It is probable that the original method of turning small craft was originally with oars, and that this method developed into the use of a steering oar, again one form of which is illustrated above and is known as a sukkan. This would have developed into the quarter-rudder, a device solely for steering and fixed to the stern quarter of a boat, from which it derives its name. This, in turn, developed into the stern rudder, a form of which is described in the preceding paragraph and is known as a pintle and gudgeon system. Nowadays this is a metal arrangement, usually iron, but Arab systems used ropes and lashings to fix the rudder.

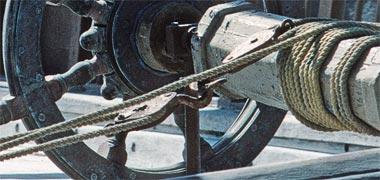

Arab sailors are said to have invented the cross beam and chain method of turning the rudder. While some claim this to be a Chinese invention, the two systems are likely to have developed independently of each other. In this case the rudder has, at its head, a cross-piece attached, at the ends of which there are two ropes or chains fixed as are shown on the first of these two photographs.

The second photograph illustrates the manner in which the chains are led through holes in the side of the craft to a position from which the helmsman can steer his way. What might not be evident from the small images placed here is that the chains are led through a pulley system fixed at one end to the ends of the cross-piece and, at the other, to the heavy circular vertical post, this system improving the efforts of the helmsman while giving greater control of the rudder. The third photograph is a detail of that above it, showing how the chain wraps round a metal sheave before being led back to the end of the steering arm and from there down through a hole in the side of the hull to the steering mechanism.

These next four photographs show the steering arrangement of a country craft where a rope system is used to move the rudder through the steering arm over the stern of the vessel.

The first two photographs illustrate the wheel from over the stern and from in front. Steering wheels on craft this size are either of six or eight spokes and are constructed of timber sandwiched between two metal plates and bolted together in order to retain their shape and strength.

The first two photographs, taken from over the stern and from in front, show how the steering wheel is supported on a triangular steel framework from the deck. Attached to the wheel is a steel spindle over which there is threaded a heavy hexagonal wooden shaft.

The surface and edges of this shaft, together with the effect created by the line being wrapped around it several times, create sufficient grip for the line to move the rudder cross beam without slipping around the shaft. The amount of friction in the line and sheave system is able to hold the wheel against the action of the water acting on it.

The two lower photographs are both details of the first two photographs. The intention is to demonstrate the fixing of the line in a little more detail. The photographs both illustrate how the lines are led through two metal sheaves which are joined by a simple hook and eye arrangement, enabling them to be readily disengaged when and if necessary.

This detail shows the simplicity of the hanging of a rudder on a bateel, this arrangement being similar to the hanging of rudders on many traditional craft. Wrought iron straps, or gudgeons, are fixed to the stern post on the right, and a similar strap to the rudder on the left, the connection being made with a pintle attached to the rudder strap dropped into the gudgeon on the sternpost strap, gravity holding the rudder in place.

However, it is the method of turning the rudder which is more interesting. Compare how this operation is effected here with that above where the rudder is operated by a horizontal bar at its head. Here, by contrast, the rudder is turned by lines from the stern of the craft running to sheaves, themselves linked to a vertical bar fixed to the back of the rudder. Evidently the lighter craft does not need the chains required by heavier craft. Note that the lines appear not to be spliced as might be anticipated, but whipped.

Anchoring

All craft need to be able to anchor when unable to tie up to a quay or jetty, traditional craft are no exception. Generally the waters off the peninsula are relatively shallow, and many of the country craft were and are run onto the shore and anchored, as shown in this illustration photographed in Wakra, or tied to an object onshore where that is practicable.

Originally, the anchoring of boats was carried out with primitive anchors comprising a large stone to which, or through which, there is attached a strong spike, known as a sinn. The stone provides a degree of security among rocky sea beds, the sinn creating additional grip both there and in sandy beds. The spike is fixed into the hole in the stone by the device of driving in two spikes, one from each side of the stone that effectively act as wedges to each other. Note that the connection with the stone is usually made with with a chain.

This photograph shows a better detail of the traditional anchors used on pearling craft and others. The main element appears to be made of faruwsh through the narrow end of which a hole has been drilled to accommodate an iron loop attaching the anchor to the craft. The sinn is missing in this case but the positioning of holes and the width of the stone at its base evidently have been estabished in order to optimise the catching capability of the anchor. Incidentally, the name sinn sometimes refers to the whole of the anchor and not just the bar.

With time, and the increasing availability and affordability of iron, the more modern anchor was developed. This took two forms. The first was a heavy anchor, known as a bawara, which was designed to hold fast in sandy or mud sea beds. A heavy one is shown in this photograph on the kalba of a boom with a lighter one partly obscured behind it. A lighter bawara is shown in the first photograph, its fluke dug into the sand.

A second form of anchor was developed and used, typically, by pearling craft. The grapnel form was lighter and more easily handled with a longer shaft that branched into four or six curved and fluked prongs at its end. Known as an ’angar, I suspect its name is derived from the English word, ‘anchor’, itself developed from Greek. The photograph to the side illustrates both the sinn type of anchor hanging from the bow of the craft but also, on the starboard bow, a version of the grapnel type. In this case it is not an open grapnel but appears to be formed of solid plates fixed to a long shaft. It is the only anchor like it I have seen.

Both of these types of anchor were usually stowed loose on deck or hung on the kalba built into the frame near the prow of the craft though, in the case of the above version of the grapnel, lashed to the kalba and suspended out over the sea. The timber bollard associated with the Traditional boats is known as a rumaana and is used for hold mooring lines.

With the passing of time, more modern anchors are being incorporated into country craft, particularly the larger and more recent vessels. Here, a pair of modern anchors can be seen fitted within the structure of the vessel in a similar manner to which anchors are incorporated in modern ships. With the advent of power winches it is now possible to have more modern anchors. In this photograph modern anchors have been added and can be seen hanging tight to the hawse hole, the new addition to the hull. Inside the dhow provision will have been made for the necessary winch to raise and lower the anchor. One point to note is that the introduction of a hawse hole will lead to the possibility of taking in water in rough seas though, commonly, sailors will stuff rags in the hawse hole to seal it at such times.

Yet many of the new and converted country craft still rely on the more traditional anchors, though the stone anchor form are only seen on the craft expressly used for touristic or traditional exhibitions. The type of anchor illustrated here, attached to the cat beam, or kalba, is one of the most commonly seen forms of anchor attached to these craft. This particular anchor is of the grapnel type, but notice that its arms are curved back significantly more than usual and has probably been designed to hold fast in a particular character of sea bed.

Oars

The term ‘oars’ is used here, though you should be aware that some refer to them as ‘sweeps’, which generally has the meaning of oars used in an open craft, each oar operated by a single person with both hands.

There appear to be two basic types of oar used for rowing traditional country craft: the ghaduf, used on fishing craft, and the suff, used on pearling craft. The first type are illustrated here by a set of oars along the starboard side of a fishing boat. It is the form of the blade that establishes them as being used by fishermen. Traditionally those blades are square or symmetrical, and are long with a relatively short shaft. This requires the oar to be entered into and operated within the water at a steep angle.

The availability of suitable timber for oars is relatively restricted so, in order for the shafts not to break, they have to be heavy, with a thick cross section, usually circular. At the end of the shaft the blade is attached by means of ropes threaded through the blade and around the end of the shaft as can be seen in the photograph above, a detail of this photograph. It is noticeable that the oar has a significant bend to it caused through use. Notice that the blade itself is a flat plank with no shaping or refining to save weight or to scoop water better.

In the above photograph you can see how the oar is attached to the rowlocks, or masaanid al majdthaaf, with hemp rope. As you can see from this photograph, the rope is wound tightly around each misnad al majdthaaf to create a degree of protection, the binding of the oar to the misnad places the oar behind the misnad so the oar is not operated directly against the misnad. This photograph, taken on one of the racing craft – jals lal-sibaaq, shows how the misnad al majdthaaf are fixed directly into the top strake of the craft, and the extent of the protective binding.

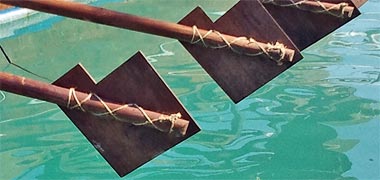

By comparison, the oars or sweeps of pearling craft have a very different and distinct shape. As can be seen in these details, taken from a photograph of a pearler, the blades of the oars are basically square and lashed to the shaft of the oar on the diagonal. These are much longer oars than seen on the fishing boat above, and appear to be mangrove poles, a common building material in traditional construction, though it is probable that the blade is made from mango wood. I don’t know why the blades should differ from those on fishing craft but suspect it may have something to do with need for manoeuvrability rather than speed. These oars were also used by the divers to hold onto when resting. Note how much longer the masaanid al majdthaaf are, and how the oars are attached near their tops rather than close to the strakes. Also note in the lower photograph how the square form of the blade has been amended – whether this is for decorative or functional reasons, is difficult to determine.

Masts and yards

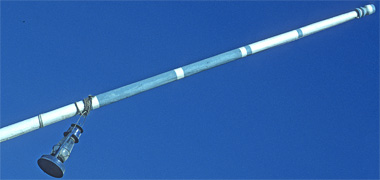

The sails of these craft are fixed to the yards, main and mizzen if there are two masts. The yard is a farman, and is known as a farman ’ud or farman qalami depending on whether it is used on the main or mizzen mast. As the mainyard is approximately the length of the vessel on which it is used, several pieces of timber are generally fixed together in order to span that length. In these two photographs you can see an extreme example of how timbers are lashed together to form a strong mainyard. The example of this boom shows that a large number of timbers have apparently been bundled together to create the mainyard. Generally there are fewer timbers and they are notched to form mechanical bonds with each other, the bindings securing them together and against slipping longitudinally.

When the farman ’ud has been constructed it is balanced in order to determine its centre of gravity and the final bindings made there, as shown in the detail photograph, in order to provide the point to hoist and lower it on the mast.

more to be written…

Sails

The extent of the use of sails on country craft seems to have altered over time. It is not just that the use of diesel engines is now the norm, but I have never seen a craft under a full complement of sails and suspect that there is rarely the need to hoist them, and even that they may no longer be carried. Nor have I ever seen more than a single sail deployed, and that only before the craft were close enough to shore for the diesel to be brought into use in order to manoeuvre with better control than the sail provides.

The largest craft, abwam, have two masts, main and mizzen, though there used to be the possibility of a small stern mast. Each of the masts carried a single lateen sail, but it is or was possible for a topsail to be set above the mainsail, a jibsail between mainmast and prow, and a small sternsail. Generally the main, mizzen and jib would form the full complement of sails at sea. This photograph shows a single lateen sail on a country craft under way in the West Bay. Note the construction of the spar to which the sail is attached.

Here a sail has been laid out on the ground of the dhow jetty in the 1970s in order to repair or strengthen it by inserting a number of panels. In this photograph the foot of the sail is on the right, the luff nearest, and the head on the left. The luff of the sail is not in the photograph. Sails are constructed of panels of sail cloth sewn together, running vertically from the foot of the sail up to meet the head on the diagonal.

The ratio of the sides of the sail are important and are determined by the captain who will take into account the conditions under which he will be using the sail, and whether it is a mizzen or mainsail. But first he will set a length for the foot of the sail. The length of the head of the sail will be a ratio between one-and-a-quarter to one-and-a-half the length of the foot, and the luff will be a quarter of the length of the head of the sail. The leech of the sail is usually the length of the head of the sail for a mainsail, but a little shorter for a mizzen sail taking account of the raised poop deck. While I have seen it written that the mizzen sail might have a longer luff, mizzen sails appear to have no luff.

When moored, the sails of traditional craft are usually furled straight away, as can be seen in this image though, if wet, they are dried on the ground as in the image a little way above.

Traditional craft can still be seen around Qatar under sail, though perhaps this has more to do with the increased interest in the nation’s past rather than a wish to save on fuel; it must have been noted somewhere in these pages that it was common to see traditional craft under sail as they moved towards the shore, and then lowering the sail so that a motor could be used to move the last short distance to shore or the craft’s mooring. This was particularly true for the larger craft crossing from the other side of the Gulf.

In this photograph two traditional craft, which I think are kitrat, are sitting with the nearer one moored by a line to the shore. The photograph illustrates how their sails are loosely furled with coir lines. There appear to be no clues on the craft as to what had or was about to happen. Nor is it clear what function the horizontal white paddle serves positioned over the rudder of the nearer craft, though there is a hint of a smaller craft behind it. It seems it might be either an unusually long oar or a steering device. For contrast, note the shape of the two oars with relatively large blades used for manoeuvering or for the occasions when there is too little wind.

more to be written…

Lines and ropes

more to be written…

Other parts

Most of the working boats have a number of other features which are present either because they are a necessary adjunct to the seaworthiness or operation of the craft or because they are necessary for the fishing or freighting activities relating to work on deck or below. One of the features which all craft have is shown here. A pump, usually operated by hand – but in the more modern craft or conversion, electrically – is always required in order to pump water out of the bilges or hold. No craft is completely watertight, so this facility is a requirement. This particular pump moves water from the lower parts of the craft directly to the sea via a pipe led through the transom, the top of it just glimpsed in the foreground here.

While the pump is a necessity for keeping the craft safe and afloat, one of the items required on many working craft is a horizontal pole set above head height over the deck, and which has a number of uses. From it, items used in the work taking place on deck can be fixed or hung, nets can be stored and dried and, when the weather requires it, canvas can be spread over it to provide a degree of protection to those exposed by working on deck.

In the first of these three photographs the pole can be seen running horizontally, fore and aft, the vertical pole against which it is clipped holding a riding light for navigational safety at night. The horizontal pole itself has a decorative treatment of bands of blue and yellow paint as is the traditional practice despite this being very much a working craft. If you compare this with the photograph three below, you will see that whereas this pole is likely to be a natural mangrove pole, that below has been milled to a standard, rectangular cross section suggesting a more expensive and recreational craft. The second photograph is of a much more highly finished and decorated pole on a country craft. Note that the vertical square pole is also decorated with a strong pattern.

In this photograph, taken in the early nineteen-eighties of a working dhow standing outside the country craft harbour with the port buildings in the background, a canvas shade has been rigged over the foredeck. This will provide necessary shade for those who will not only be working on deck as the craft is unloaded and loaded – this dhow seems to be sitting relatively high out of the water indicating it may be waiting cargo – but will also be living on deck during their time in harbour as well as when out at sea.

In this photograph the end of the horizontal pole can be seen with the typical arrangement for clipping or slotting it into the vertical pole. In this example, the vertical pole has a sawfish bill attached to the top of it. It is difficult to say exactly why people do this, but in addition to there being a probable decorative purpose, there may also be thought to be an element of good luck or, perhaps more precisely, warding off evil – an apotropaic belief – conferred on the vessel and crew by this addition. Incidentally, I understand that the saw is that of a mature green sawfish, Pristis zijsron, a species which is in rapid decline within the region.