a collection of notes on areas of personal interest

- Introduction

- Arabic / Islamic design

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 01

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 02

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 03

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 04

- Islamic architecture

- Islamic urban design 01

- Islamic urban design 02

- Islamic urban design 03

- Islamic urban design 04

- Islamic urban design 05

- Arabic / Islamic gardens

- Gulf architecture 01

- Gulf architecture 02

- Gulf architecture 03

- Gulf architecture 04

- Gulf architecture 05

- Gulf architecture 06

- Gulf architecture 07

- Gulf architecture 08

- Infrastructure development

- The building industry

- Environmental control

- Perception

- The household on its lot

- A new approach – conceptual

- A new approach – principles

- A new approach – details

- Al Salata al jadida

- Public housing

- Expatriate housing study

- Apartment housing

- Pressures for change

- The State’s administration

- Society 01

- Society 02

- Society 03

- Society 04

- Society 05

- Society 06

- History of the peninsula

- Geography

- Planning 01

- Planning 02

- Population

- Traditional boats

- Boat types

- Old Qatar 01

- Old Qatar 02

- Security

- Protection

- Design brief

- Design elements

- Building regulations

- Glossary

- Glossary addendum

- References

- References addendum

- Links to other sites

Municipality planning

Following the Second World War, building development steadily increased in pace, particularly in the capital, Doha. In response to this the government, in 1963, introduced the Municipality of Doha, giving it four responsibilities:

- building process,

- gardens,

- public health, and

- accounts.

This new agency introduced the first requirements for the construction of buildings, a site location plan, but with no process for its enforcement. This municipal administration was the only form of local authority until 1971 when, with independence, a ministry structure was introduced, one of which being the Ministry of Municipal Affairs.

The situation in which the ministries found themselves was novel and a dramatic change from the traditional way of managing affairs. Consultants were brought in, the Ministry of Public Works introducing Llewelyn-Davies, Weeks, Forestier-Walker and Bor to review and recommend how the peninsula might be planned and managed. Their work included:

- a structure plan for the whole of the peninsula,

- reports on population and its alternative projections,

- recommendations on land allocation, building heights, transportation and services networks,

- town planning designs for Doha,

- detailed designs for residential areas,

- detailed designs for the planning of the central area of Doha, and

- building laws and regulations for the control of planning and building construction.

The consultants continued to work on developing the structure plan but, by 1978 it was evident that the pace of development was outstripping the facility of government to control it. The following year the Ministry established its Town Planning section for the Municipality of Doha, Ll-D having had its contracts moved to the Ministry of Municipal Affairs in 1974 in order to recognise and make more apparent the distinction between planning and construction.

Meanwhile, Llewelyn-Davies continued to work on the centre of Doha, their remit changing with time to more detailed work on the identification and design of Action Areas and, particularly the design of Grand Hamad, the road driven north-south through the middle of the centre of Doha. Ll-D were also awarded the design and construction of the major hospital that replaced the old Rumaillah Hospital.

By 1978 it was evident that the pace of development was outstripping the facility of government to control it. The following year the Ministry established its Town Planning section for the Municipality of Doha, Ll-D having had its contracts moved to the Ministry of Municipal Affairs in 1974 in order to recognise and make more apparent the distinction between planning and construction.

Shankland Cox Partnership were introduced in 1979, their remit beginning with the:

- examination of existing planning data and policies, recommending additional data requirements and areas where existing resources could be improved; advising on the design of a planning land bank or storage system and the implementation of such a system,

- updating or revising to appropriate scales the existing development plans for Doha and the major villages,

- producing Action Area plans and detailed physical development guidelines where appropriate,

- reviewing and advising on existing physical planning and development control procedures, and

- reviewing the existing Ministry staff structure and assisting in training existing and new staff.

This work was followed up by specific studies and recommendations for:

- an outline for the Qatar Area Referencing System – QARS,

- a planning database,

- the Doha Interim Structure Plan, 2000,

- the Doha and New South District Interim Development Plan, 1990,

- Doha City Centre Interim Development Plan,

- Action area plans for

- the new Suq,

- Grand Hamad road,

- Jasra road,

- Asmak street, and

- feriq al-Salata, and

- a legal framework for implementation,

this latter advice being professional advice on establishing a set of improved building codes for the State, to be enacted and enforced as a continuation of the work of the Ministry of Municipal Affairs.

By this time the Planning Section of the Ministry was essentially structured to look only at development within Doha, its original structure being associated with:

- development control,

- land control and sub-division,

- urban design, and

- utility coordination and liaison.

Land control and sub-division also dealt with the increasing problems relating to land adjustment. The initiative to develop land had encouraged many to have their land appropriated and compensated. The situation with regard to boundaries was complicated by the increasing value of land and its reflection in the number of land agents and their operation.

During this period, from the late-1970s to the late-1980s, government settled into a period of consolidation, attempting to bring its institutions up to speed while keeping pace with the rate of development. This required increased cooperation between ministries and their staff, but also the continuing use of consultancies. Bear in mind that individuals and agencies were introducing consultants to the country to work on a variety of projects in the public and private sectors, the former including projects for oil and gas, security and the military.

It is notable that, during this period, the rapid pace of development slowed as a reflection of revenues from oil and gas which slide during the 1980s. In government, the opportunity was taken to continue to innovate, one particularly useful initiative being the introduction of a Geographical Information System to enable improved accuracy and with it, better information and coordination.

This period also saw the Doha Planning Section established its Urban Design and Land Use Standards and Regulations. Generally these followed the recommendations that had been accepted and adopted for development in the New District of Doha.

Municipality planning standards

The Municipality established a series of standards that it now sought to implement not only in Doha but by extension, in the rest of the peninsula. Here they are in order to illustrate the thinking at that time. Bear in mind that this work was completed after the introduction of novel requirements in the New District of Doha.

Housing

Plot sizes are to be 30m x 30m when sub-dividing vacant land, this also being the standard for Senior Staff housing.

Plot coverage is to be a maximum of 60%.

A Floor Area Ratio – F.A.R. – of 1:2 is permitted.

Car parking of 1 space per dwelling unit is a required.

A maximum height of 11 metres is permitted within which a basement, ground floor, first floor and penthouse have to be accommodated.

House structures are classified as:

- Main structure – the principal building intended to be the residential quarters of a plot, and

- Secondary structures – ancillary buildings on the same plot which may be separate from the main housing structure. Secondary structures include servants’ quarters, separate majlis, garaging and storage facilities.

The following housing types are possible within the density ranges permitted in residential areas:

- Villa – an individual housing unit,

- Patio or courtyard house – an individual housing unit organised around a central open space,

- Row house – individual housing unit on its own lot which abuts its side lot lines and joins row housing units side-by-side or in more than one storey, on a single site,

- Duplex – an individual housing structure with two housing units side-by-side or in more than one storey, on a single site,

- Townhouse complex – a housing structure with three or more dwelling units side-by-side, on a single site, and

- Block of flats – a multi-family walk-up or elevator-serviced housing structure.

Gross residential density is the total number of dwelling units that may be built within a sub-division, divided by the total area in hectares, including all local, access, and the loop roads, culs-de-sac, pedestrian paths and local community facilities.

Residential zones are classified by gross density under the following categories:

- Very low density – an area with an average gross residential density targeted to 5.25 dwellings per hectare. This density level provides for lots of up to 1,200 sq.m., allowing for the construction of spacious single-family detached housing or either the villa or patio or courtyard house design configuration.

- Low density – an area with an average gross residential density targeted to 6.75 dwellings per hectare for the construction of single-family housing on moderately sized lots. Possible housing types include detached villas, patio or courtyard houses or row houses.

- Medium density – an area with an average gross residential density targeted at 10 dwelling units per hectare. Many housing types are possible at this density, including detached single family units on smaller lots, single family cluster housing, townhouses and duplexes.

- Medium high density – an area with an average gross residential density targeted to 20 dwelling units per hectare. The housing types in this density category include attached units such as townhouses and duplexes, as well as low-rise blocks of flats.

- High density – an area reserved for the construction of walk-up or elevator-served blocks of flats with an average gross residential density of 30 units per hectare.

Lot sizes for the above densities are:

Housing type |

Minimum lot – sq.m. |

Maximum lot – sq.m. |

| Villa | 350 | 1,200 |

| Patio or courtyard house | 160 | 250 |

| Row house | 160 | 250 |

| Duplex | 200 per unit | 600 per unit |

| Townhouse | 120 per unit | 200 per unit |

| Block of flats | 720 | 180 per flat |

Sub-division design – a residential sub-division is a planned division of land into lots and public rights-of-way to provide sites for future individual buildings. A sub-division plan may consist solely of residential lots and public rights-of-way. It may also contain lots set aside for community facilities, including those specified by the government. Design criteria concerning proposed sub-divisions are listed as follows:

- Sub-division design shall conform to the land use designations, development densities and housing types specified in the Land Use Plan and in the site specific Planning and Urban Design Regulations for the area.

- In residential areas where a sub-division plan has been established by the government, all roadways and building lot boundaries shall be treated as fixed conditions.

- In cases where a sub-division plan has not been established by the government, the distribution and utilisation of land may be determined by the developer, subject to the following conditions:

- Land shall not be sub-divided for development in areas where soil, subsoil or flooding conditions create dangers to health and safety, unless proper provision is made to correct these conditions. The layout of the area shall be compatible with natural and developed features of the area and surrounding regions.

- The area shall be organised to provide both an efficient layout of infrastructure systems and a pleasant and sociable living environment.

- Orientation of streets, lots and buildings should be generally parallel or perpendicular to true north in order to minimise the impact of solar exposure on buildings. Orientation along a north-west - south-east axis should be avoided in order to minimise exposure to severe winds from the north-west.

- Service facilities and higher density housing should be located so as to facilitate access and minimise traffic to them through lower density housing areas.

- Consideration should be given to grouping lots to create small local areas in which residents may share common facilities. Mixing housing types and lot sizes within the sub-division is encouraged so that the resulting neighbourhood will be more heterogeneous.

- Leftover or unassigned land areas are to be avoided. All land within the residential area shall be developed or treated.

- Set-backs – the front, rear and side walls of each house type shall have the following minimum set-backs from the boundary of the plot:

Setbacks from the… |

With windows |

Without windows |

| Front | 5.5 metres | |

| Rear | 3.0 metres | 1.5 metres |

| Left side | 3.0 metres | 1.5 metres |

| Right side | 3.0 metres | 1.5 metres |

Non-residential uses

Non-residential uses permitted in residential zones include:

- Local commercial – an area for commercial services or convenience retail sals of limited scale such as cafés, restuarants, news stands, tobacconists, drug stores, flower shops or small grocery stores generally provided for the everyday use of residents living in the immediate area.

- Local mosque – a site designated for a small daily mosque serving the residents of the immediate area.

- Outdoor majlis – a small pocket park providing a social gathering area for adults residing in the immediate vicinity.

- Children’s playlot – a small pocket park or ‘tot lot’ allowing young children a safe public play area.

- Social centre – an area for a social centre of club facilities.

- Recreation centre – an area for recreational facilities such as a swimming pool, sports courts, playing fields and a club house.

- Public park – a site designated for a public park or garden for passive recreation.

One of the principles established by all the planning consultancies engaged to advise on planning issues was the need to produce a hierarchy of facilities responding to the requirements of the inhabitants of the peninsula. For instance, in terms of roads, these would respond to the traffic loads ranging from the requirements of inter-city arterial highways down to local distributors and roads leading to individual houses.

In terms of retail facilities there is a general understanding that there should be a range of shopping experiences from the large regional centres with their collections of brand named goods, supermarkets and associated facilities through district centres down to the small corner shops catering for the day-to-day needs of the residences among which they are situated.

This arrangements allows local residents to buy a limited range and number of goods, usually foodstuffs, quickly and on foot without having to travel by car to larger centres where they may have to buy larger quantise than they need.

Perversely this policy may be reversed in 2013. These local shops are being blamed for traffic problems in and around residential areas, with the government intent now to bring them under a single roof, in effect, local centres. However, the small shop has a long tradition in the country, many of them expansions of garages where the owner has the advantage not only of making profit from a small-scale retail facility, but of the staff employed there also to carry out other duties for him.

But they also offer immediacy, safety and a continuation of a socio-cultural tradition. It appears that for traffic to have become this much of a problem, there must have been an unplanned expansion of these small shops, as well as a poorly planned relationship with housing.

Road network and hierarchy

All roads and streets shall meet the design standards set forth by the Ministry of Public Works Civil Engineering Department – Roads Section and Design Review Committee will be required. Road types can be defined as follows:

- Regional, primary, secondary and local roads are normally situated outside or on the perimeter of any residential area.

- Access roads, loop roads and culs-de-sac provide vehicular access within the residential area. In residential areas where the road network and land sub-division plan have been established by the government, all roadways and building lot boundaries shall be treated as fixed conditions. Where roadways and building lots have not been established by the government, internal streets may be designed by the developer, subject to Engineering and Planning Controls. Where internal vehicular circulation is designed by the developer, the following apply:

- all habitable buildings shall be provided direct vehicular access.

- The circulation system should follow the established road system hierarchy with traffic descending from primary or secondary roads to local roads, thence to access roads, loop roads and culs-de-sac, and finally to individual lots.

- Streets should be sized according to intended traffic load with culs-de-sac carrhing the least traffic and loop roads, access roads and local roads carrying increased traffic loads respectively. Local roads shold provide the link to high volume primary or secondary roads.

- Internal streets should be designed to discourage through traffic. This can be accomplished by use of loop streets, culs-de-sac and T-intersections. Four-way intersections are not allowed.

- Where appropriate, internal streets in a residential area should connect with streets in adjacent areas. If connected, the road reservation of both streets should be equal. Where street systems of adjoining residential areas have not been constructed, it is the responsibility of the developer to identify the location and status of adjoining streets to ensure maximum coordination.

- In general, streets should intersect as nearly as possible at right angles both for reasons of safety and to avoid difficult lot design problems. Intersections of more than four streets are not allowed.

- Internal street systems shall be designed to accommodate not only vehicular circulation but also pedestrian circulation and utility systems. Roadway reservations shall include space for sidewalks and utility lines as determined by the relevant government authority.

- Grades on internal streets shall be not greater than 8% nor less than 0.5%.

- Tangents between reverse curves of an ‘S’ curve on local or access roads shall be a minimum of 50 and 25 metres respectively. The minimum radius of all internal roadway curves is 50 metres.

- Corners at intersections must be rounded to permit safe turns.

- Visibility as intersections must be provided by means of a clear zone within which no wall or object taller than 0.4 metres is permitted.

- Streets shall be designed according to the topography of the area to minimise grading and facilitate surface drainage.

- Stop signs shall be provided at the intersections of local roads and access roads.

- Vehicular access to individual building lots is permitted only from local roads, access roads and culs-de-sac. No direct access is allowed from primary or secondary roads. Parking requirements in residential areas are as follows:

- Parking in residential areas is to be located principally on building sites or in off-street parking areas.

- Street parking is discouraged. When street parking is permitted by the Site Specific Regulations, it is to be designed as lay-bys differentiated from the traffic roadway by construction materials and lane striping. Lay-bys or street parking are not permitted within the clear zones required at intersections.

- Off-street visitors’ parking shall be provided within convenient walking distance of the units to be served in parking bays off the traffic lanes of residential streets.

On-site parking

- On-site parking shall be provided for each housing type according to the minimum standards given below:

- Minimum car parking requirements:

- Villas – 1 per dwelling plus 1 per additional 200 sq.metres.

- Flats – 1 per dwelling up to 16 flats plus 1 per additional 4 flats.

- On-site parking shall be provided for each non-residential building type as follows:

- Commercial – 1 space for each 25 square metres of net usable floor area.

- Educational – 1 space per classroom plus 10 spaces.

- Religious – 1 space for each 10 square metres of total prayer area.

- Recreational – per programme requirements.

- Minimum car parking requirements:

Service access

- Wherever possible, access for delivery traffic should be separated from other traffic and designed not to interfere with pedistrian traffic. All outside storage and dock space shall be visually screened from parking areas and pedestrian systems by a landscaped wall at least 2 metres in height.

Bicycles, motorbikes and motorcycles

- Provision shall be made for access and parking of bicycles, motorbikes and motorcycles in appropriate, distinct locations.

more to be written…

The Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Agriculture has been responsible for the physical planning within Qatar. Its Urban Planning Department controls this through the medium of its plans, this to the side being the Greater Doha Structure Plan which is stated as intending to establish and control development through to 2030. The plan incorporates six inter-related components – current and proposed physical development patterns, land use, community facilities, transportation, utilities and the environment – all within an interactive framework.

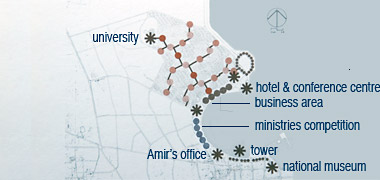

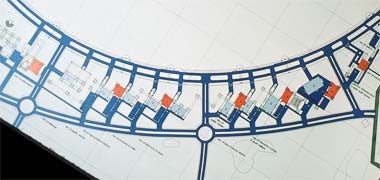

This illustration indicates the planning of land uses around the West Bay about 2003. Taken from a document prepared for the second ministries competition in 2003, and illustrating the intentions of the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Agriculture’s Urban Planning Department, you will notice a significant change along the Corniche where the area recommended for the ministries in the WLPA 1979 plan has been changed to landscaping. The business district and public plaza elements of the NDOD remain the same. In urban design terms the change signifies a reinforcing of the visual separation of the two urban centres – the NDOD and the old centre of Doha.

more to be written…

Urban Planning and Development Authority

more to be written…

National Plan

The impetus given to the development of Qatar by Sheikh Hamad saw the introduction of Louis Berger and Hellmuth Obata and Kassabaum to the planning process in Qatar in 1997. 1994-1996. ???

more to be written…

Ministries competition

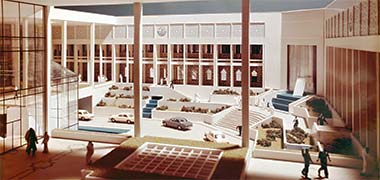

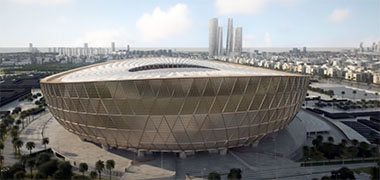

One of the important initiatives intended to encourage development within the new plan for Doha was a competition for the design of a ministries complex for Doha. The competition was initiated in 1976. This particular element of the Corniche was seen to be an important physical link, joining the business district of the NDOD with the Diwan al-Amiri and existing centre of Doha, an area with no development on it other than the Ministry of the Interior on feriq al Bida and the National Theatre at Rumaillah. It was intended that this result of the competition would run along the Corniche, focussing on the West Bay, and establish a high standard of design.

More than this, the project was understood to be an extremely important initiative as it would hopefully resolve a number of issues that were becoming increasingly apparent with the administrative, organisational and physical development of the State in its different aspects, as well as promoting the image of Qatar both within and outside the country.

Firstly, the project was intended to fulfil, or at least seed, the growing need for government offices that were not required to be either security discrete or location-specific. Secondly, it would be one of the projects intended to establish high standards of design and construction, the others being the Hotel and Conference Centre, the University and housing for Government Senior Staff employees. Thirdly, the development would join the existing group of government offices immediately north of the centre of Doha with the State Plaza, the other side of which would be more business related and occupied by quasi-governmental organisations and private business. Fourthly, and in urban design terms, it would create an organised façade to the Corniche which was conceived as having a recreational and ceremonial status in the road hierarchy, thus creating a recognisable face for the emerging capital of the peninsula.

A brief was prepared by the Technical Office of H.H. The Amir, and four well-known if not famous architectural companies from different countries were invited to compete with outline schemes for the ministries complex stretching from the Office of H.H. The Amir in the east to Khalifa Road in the west, this being the main traffic distributor leading from Medinat Khalifa and al Markhiya into the State plaza which was recognised as being the gateway to West Bay. In effect the scheme ran to the National Theatre site on the southern boundary of the State plaza, and incorporated the Ministry of the Interior building at feriq al Bida. The architects invited to prepare schemes for this limited competition were

- The Architects Collaborative,

- Gunther Behnisch,

- James Stirling and

- Kenzo Tange & Urtec.

A fifth architect of similar status was invited to participate in the competition, visited the country, was briefed and taken round the site by helicopter, but declined.

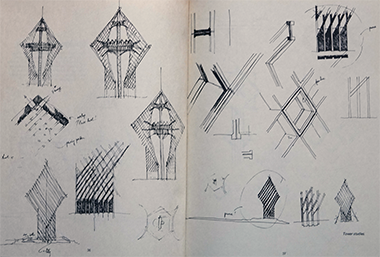

The four illustrations above are taken from the schemes submitted by the four architects and are interesting in many ways, unusually illustrating quite different approaches to their urban design solutions – though all responded accurately to the design brief.

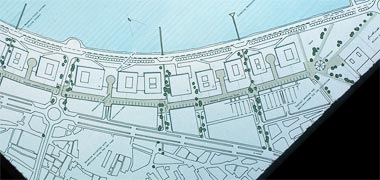

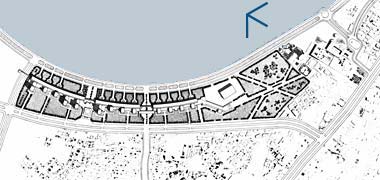

The lowest of the four illustrations above, this plan and the detail photograph, are all of part of the model of the winning Kenzo Tange and Urtec scheme. In it the prestigious offices and elements of the ministries form a continuous band at the front of the scheme parallel with and looking out north over formal landscaping and the Corniche into the West Bay, with the standardised working offices behind them, capable of expansion, and taking their day-to-day access from the service road developed parallel with the Corniche. Vertical circulation for the offices was to be organised within circular corner towers which gave a particular character to the project, and the long axes of the offices themselves radiated around the West Bay rather than being designed on north-south or east-west axes, as was the normal practice.

Regrettably the winning project never got off the ground due to a number of difficulties, particularly in deciding practicalities and coordination with regard to the different ministries originally selected to move to the site. But there were additional difficulties. There had been considerable problems in obtaining the spatial schedules and functional requirements from those ministries selected to move, many of whom continued to wish to build in locations that were in conflict with those of the notional plan to set them along the Corniche or within the New District of Doha, and who found continual reasons to revise quantities or amend their other requirements. There were additional difficulties relating to identity for the ministries, nearly all of them wishing to have their image distinguished from others. In retrospect none of the problems experienced was unusual and might have been better understood and managed at the time.

Nevertheless, the Tange scheme was progressed and developed, taking into consideration the changing parameters as and when they could be agreed and confirmed. The two illustrations above show an intermediate and final view of the Tange scheme, radically different from the original concept but, ultimately, not built. It is interesting to speculate how this might have affected subsequent development had that initial scheme been constructed.

More recently, in 2003 the process was repeated, albeit with different requirements but reflecting a similar intent in providing a face to Qatar by transforming the Corniche. The architects invited to participate were

- Patrick Berger,

- Zaha Hadid,

- Kamal Louafi,

- Jean Nouvel,

- D. Paysage Architects, and

- Martha Schwartz Inc.

The Doha Palace project

The Diwan al-Amiri is, or was, the two-storey building from which the country was officially governed by Sheikh Khalifa from 1972, though previously he had worked from offices in Government House. This aerial view of it, taken from the north-north-east, was made in March 1976, and shows it occupied with the cars of staff parked in front of it and with works in hand on the landscaping between it and the Corniche. The Clock Tower is just out of picture, top left.

There are two reasons for its inclusion on one of the pages dealing with planning. The first is that it was seen to be an important urban element in the planning of new development in Doha, and should be understood in its relationship to the ministries project above. Secondly, the process of creating the later development is thought to be important in the development of an architectural vocabulary suited to Qatar.

In the early nineteen-seventies the Diwan al-Amiri occupied a prominent position west of the centre of Doha, as illustrated in the photograph above taken in 1976. The development consisted of offices at first floor level wrapped around two courtyards – four sides of the northern courtyard and two of the southern. Originally the structure at first floor level had open corridors onto the courtyards, but they were both enclosed by simple glazing by 1972. North-west of the northern courtyard was the structure which had been built to house Sheikh Ahmed, but never finished or occupied. On the ground floor were mainly State function rooms, particularly a majlis and dining room. Although the Diwan appeared to be, and is, a large building, there were relatively few people housed in it. So, with the need to house increasing numbers of people in the Diwan al-Amiri, plans were initiated to find a useful way of enlarging the building.

This was also seen as an opportunity to establish a strong urban design element at the south end of the West Bay, in effect a focus for the intended development that was to stretch around the bay. It would link the existing government buildings to its east with the ministries project which was to extend west to the State Plaza and would also be a focus for these existing and new developments.

This aerial photo shows the location of the block on which the Diwan al-Amiri sits, the new building being the symmetrically arranged three blocks with a large courtyard to its south. The old Diwan al-Amiri is located to its right, or east and, east and south of that, are the clock tower and Grand Mosque. The site for the whole complex was originally chosen as being on high ground west of the centre of Doha.

Here, for comparison and contrast are two images of the Diwan by day and by night from approximately the same position. In the lower image, the modelling of the strong façade has been accentuated by uplighting the structure with two shades of lighting, blue and red. This has given additional articulation and definition to both the elements and structure of the building, the shadows assisting in breaking up the line of the cornice.

The character of the buildings is deliberately heavy in order to fulfil a number of design requirements including not only a relationship with traditional buildings but particularly environmental control with its small percentage of fenestration.

The massing of the building is articulated into three elements with the stepped structure over the atrium both apparent and echoing the stepped feature found on the parapets of some structures but, obviously, in a three-dimensional manner rather than the two-dimensions of the original. Vertical circulation is expressed and which breaks up what would otherwise be a heavy horizontal cornice.

The external façade is heavily articulated as well, the columnar structure reflected in its rhythm, but with pre-cast concrete units hung on it, each decorated with a variety of patterns developed from the naqsh panels found in traditional buildings, and with the cornice element broken by extensions that were intended to call to mind traditional maraazim.

But stepping back in time a little, by the late 1970s, the Diwan al-Amiri was essentially a series of rooms served from a wide corridor wrapped around two courtyards on two levels. Combining solutions to both the needs for office space, a more international setting for the important State functions carried out within it, and an urban design element for the developing Corniche, the first initiative for expansion suggested that a building might be created in the angle between the Diwan al-Amiri, the unoccupied extension to its north-west, the Corniche to its north and the access road from the Corniche to the Clock Tower roundabout. A design brief was produced by the Diwan’s Technical Office with a relatively modest schedule of requirements that were to be contained in the new and refurbished buildings. These first two sketch models illustrate something of the thinking behind the project and its external appearance.

In the above two photographs of the project model – illustrating how the scheme might appear from approximately the north-east – the location of the new building can be clearly seen together with the new façades intended to tie the new building visually to the older structures. Note also the intent to create a large plaza immediately to the east of the Diwan incorporating the Clock Tower, and to relocate the access road further east to accommodate this.

Designed by the Japanese architect, Professor Kenzo Tange, the schematic design shown above was developed into a full design within the constraints of the site, this first photograph illustrating the finished presentation design from a northern, aerial perspective. The Clock Tower and Grand Mosque can be seen in the top left of the photograph with the Corniche out of picture at the bottom of the photograph.

While it was envisaged that the scheme could be expanded both to the south and west, there arose a concern for the proximity of the main offices to the Corniche. It was then considered that for both security and urban design purposes, the building should be set further back from the Corniche in order not to act as a visual stop to the run of prestigious buildings that were envisaged running from the Sheraton Hotel at the end of the West Bay through to at least Government House, east of the Diwan al-Amiri.

In this aerial view of the model viewed directly from the east it is possible to compare the differences between the sketch design and finished design models. A major urban design change will be noted: the concept of creating a large urban square immediately to the east of the existing Diwan al-Amiri by the introduction of a strong architectural device, a colonnade, was dropped in favour of keeping the existing road pattern and allowing the staff parking to remain at grade in that area.

Although significant consideration was given to the issues relating to the main entrance to the extension, particularly security, it is evident that the solution shown would neither benefit ceremonial aspects of the development nor be particularly secure.

In retrospect it can be thought that this decision did not permit the breathing space in front of the Diwan al-Amiri which it deserved when looked at from an urban design point of view; and it was considered that, while creating a beneficial public space connecting the Diwan with the Grand Mosque to its south-east, the colonnade would have obscured the newly installed eastern façade of the building.

The third of these five images shows the main entrance façade of the building, looking directly from the north-east. The long, unbroken line of the roof may seem unusual in the context of the traditional architecture of the peninsula, but it replicated that of the relatively modern existing buildings.

The last two of these five photographs of the model illustrate something of the character sought for the new entrance area. The modelled, naqsh decorated, pre-cast concrete finishes intended for the area would be complemented by banked areas of planting alternated with water features intended to bring colour, movement and coolness to the enclosed space.

The images look approximately south and south-west from within the extension across the contained entrance courtyard.

Although they are too small to discern at this scale, the ogee headed windows of the original building can be viewed through the rectangular openings in the new extension.

For a number of reasons the initial project did not go ahead and it was decided that the site for the new building should be moved further west onto the site of the old, unoccupied extension.

The concept for this new site was initiated within the Technical Office of the Diwan al-Amiri with the original scheme forming the basis for a revised brief. This was then developed into an architectural scheme, the Technical Office working with the international architectural company, Rader Mileto and Batori. This preliminary model shows a single height of building with the central atrium yet to be defined. An element of the landscaping was suggested at this point with a water feature which would have run down to the Corniche.

The next photograph, again an aerial view from the north-west of one of the models, shows the project at a fairly advanced stage when the organisation and massing had been agreed upon and the project was about to go into design development. The central atrium was now defined as an imporant element of the design, allowing light to enter what was seen to be an important space. The lower photograph is of one of the many exploratory studies made in examining elements of the building, in this case the external cladding where the intent was to develop a façade which had a traditional architectural character responding to the prevailing environmental conditions, and was suited to high quality pre-cast concrete construction methods.

Design studies were begun at an early stage within the Diwan al-Amiri in order to be able both to establish a suitable character of architecture as well as develop a brief responding to the requirements of the client. This was seen as an imperative for this important building in order to investigate, clarify and resolve many of the expectations which the building had to incorporate. This photograph shows part of a working model used to investigate how the façade might be articulated, and can be compared with the photograph of the finished building on another page which also looks at the Diwan al-Amiri, but from a more urban design perspective.

Developing such an architecture is difficult and requires a coherent basis from which to develop a new style. The most obvious problem is that of scale as the traditional architecture of the peninsula is essentially residential. The Diwan is an office building and incorporates some extremely large spaces, specifically a central, enclosed atrium and a State majlis and ghurfat al sufra, the State dining room. But many of the offices are also large and there are substantial circulation spaces needed to match the scale of the development. This photograph of one of the earliest stages for the building illustrates something of the problem of massing while reflecting the decision to have three wings surrounding an imposing central atrium.

Further work on the project by the Diwan al-Amiri design team saw more work on the massing with, essentially, more articulation of the four elements together with the natural connection with the older Diwan al-Amiri to its east. These two models, illustrating the massing when seen from, respectively, the north-west and north-east, show how there was an attempt to open the structure to permit external stairs and fountains to link the internal atrium with the immediate exterior and, from there, the Corniche and West Bay.

At the same time as this exercise was being carried out, studies were being made on the layout of the internal spaces within the three wings as well as their linkages with an older traditional building to its south which had to be incorporated within the development, together with the various security implications relating to the offices of a Head of State.

For a number of reasons, the project was established as a series of packages, the whole of these being managed by a team under the direction of the Diwan al-Amiri. This enabled a considerable amount of detail to be expressed in the different package briefs in order to obtain a coordinated design approach, particularly in terms of the physical design of the project.

One of the first of these packages was that for the demolishing of the old structure immediately to the north and west of the Diwan al-Amiri which had been designated as the site of the new Diwan al-Amiri. This part of the Diwan al-Amiri complex had never been completed nor, of course, either lived or worked in, though originally conceived as being residential. Illustrated in the upper of these two photographs, the thickness of the original reinforced concrete wall construction can be plainly seen.

The lower photograph shows, taken from the same position as the upper photograph, one of the first site preparation activities, that of making up and levelling the ground prior to the first construction stages of the new building, foundation development and piling.

Concomitant with work on the development of the project, exploratory work was being carried out at the newly established pre-cast yard to the north of Doha in order to obtain the required high standard for the elements which were to be used to clad the Diwan al-Amiri as well as the panels and other plaster elements which would be used inside the building.

This first image shows a rubber lining used in producing smooth cast plaster panels for the interior, but it was also considered extremely important to obtain a quality of finish which would both resist the build-up of the local wind-borne sand and dust and which would also catch the light on the pre-cast concrete panels which facing the building.

A variety of samples of quartz aggregate sourced locally and from the region were tested and a selection made of a suitable character to form a part of the mix for the panels, some of which had patterns cast into them replicating some of the patterns to be found in traditional naqsh plaster carving.

With agreement on the character of the concrete mix, test panels were cast and standards agreed after which the moulds were adapted and the complex cladding panels were then cast in flexible moulds, individually checked, transported to site and lifted into place and secured to the reinforced concrete frame.

The external character of the building relies heavily on the trabeated form of the structure which is lightened – just as it often is in traditional buildings – by the use of semi-circular headed openings, themselves further softened at close range by the naqsh patterning in the pre-cast concrete.

Within the building a closer rhythm of the ribs is continued through to the atrium, the dramatic and central space of the building, with the ribs extending vertically to the ceiling where the work of the Syrian craftsmen is the horizontal focus.

The image on the right is a detail showing some of the decorative timber mushrabiyaat work between the ribs. A little more is written about this part of the project works further down the page, but this traditional carved and decorated timber craftsmanship included not only the panels between the plaster ribs, but also the central feature from which hangs a large decorative chandelier as a focus to this central space.

From the beginning of the project there was an intent to create a building which reflected something of the traditional character of the architecture of the peninsula, hopefully an exemplar that might move the discussions on the relevancy of traditional design to the present.

Elsewhere there are notes about Gulf architecture and the elements which are recognisable as being from the region, if not the peninsula. But they are relatively few; mud or stone construction, trabeated openings, ventilating and water shedding features, decorated doors, carved plasterwork and occasional painted patterns, mostly on ceilings.

The design intent was to ensure, among other requirements, that the external and internal design elements were seamlessly integrated – a coherence which is often notably missing in modern designs – and reflected an individual character of the State based on its traditions and past.

Compounding the problems contained within the design brief, there were no buildings of this size and scale existing in Qatar to act as examples or for guides to fulfilling the design requirements. This created an opportunity that demanded considerable thought and direction on the part of the design team.

Although external design consultants were used in the development both of the building as well as its fixtures, fittings and furniture, much of the definition of design and the consolidation of details was carried out in Qatar, particularly within the Diwan al-Amiri using spare offices at the south of the buildings as well as in the old majlis building in the south-east corner of the Diwan complex.

In this first photograph, the late Bruno Fiorentino, an Italian interior design consultant, is seen presenting and discussing design details with members of the Technical Office and other consultants in one of the Diwan offices. Below it is a photograph of a working drawing based on the traditional patterns found in the peninsula, representative of the many investigative and working drawings produced for the project.

Many of the designs suggested for incorporation in the Diwan were taken forward as test samples in order to guage how they might appear, particularly against other design elements of the finished building. With material samples it was not only important to see how the suggested colours would look, but also how their texture would both appear and feel. Here is an example of a design on a pale blue field, obviously related in its geometry to the drawings shown above, illustrating the richness of its textured material and embroidered gold design. The sample, approximately 300mm across, also shows considerable eccentricity in the accuracy of its execution, perhaps more reminiscent of the older naqsh examples carried out in situ.

In this photofgraph, two of the design team are seen working inside the old majlis building. It was a very useful place in which to meet and work with good quality traditional old naqsh on the walls and a traditionally painted ceiling design similar to the first floor ceiling at the old palace of Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim in feriq al-Salata. A detail of one of the corners of this majlis is shown on another page which looks at the design of traditional naqsh work. Note the temporary lighting in both photographs, later taken out and replaced with a more appropriate system of lighting for this important building.

The design work carried out by the team both in Qatar and abroad resulted in a large number and variety of designs for the fixtures, fittings and furniture that would eventually find their way into the different spaces of the building, and which had to be coordinated carefully to maintain coherence over the whole of the building.

The overall design of the development was carefully established and defined through a process of experimental development, and from these exercises many of the internal elements of the building were packaged into a number of design/build contracts related to each other through design and performance specifications. These were required to fulfil a series of highly specified performance briefs, but which allowed a considerable degree of invention and novelty within their remit.

In different parts of the world elements of the building were fabricated for eventual transport to site and integration into the Diwan.

The timber constructions, like some of the other elements of the buildings, were extremely large and required the rigorous selection of woods whose drying and moisture content had been carefully controlled along with special construction techniques with proper attention to fixing devices and glues. In this photograph a large decorative timber feature is being put together under controlled conditions prior to being transported to site and fixed in place.

The timber work throughout the Diwan was of a high quality, but there were also special features on which a lot of time and effort was expended to create elements that were particularly redolent of the character of the traditional architectural features of the peninsula, but had significant attention to their design and construction. Such a feature is shown in this detail with inlay work, studs and lapis lazuli stones in bezel settings.

Earlier it was mentioned that work on the palace was carried out and delivered from many different countries in addition to Qatar; bronze work from Germany and Italy, ironmongery from England, doors from Honduras, carpets from the Philippines and decorative timber from Syria, for instance. These two images were taken in an artisanal factory in Damascus where a number of elements of the atrium’s ceiling were fabricated and assembled in the traditional manner, these including the decorative inserts between the plaster ribs of the central atrium.

The image above shows the atrium’s twenty-four pointed central feature, shown above, being assembled and decorated by hand in the workshop. This photograph is of a young worker sitting in a corner of the workshop assembling some of the mushrabiyaat that were to be inserted into the high levels of the atrium. It is notable that the standards of workmanship are quite different, but it was considered important that traditional crafts were used where possible.

Following the striking of the shuttering for the central atrium light scaffolding was erected in order to install the white marble cladding finish as well as to fix the steelwork required to hold the plaster ribs and, at the top and centre of the atrium, to install the decorated Syrian timberwork forming the focus of the atrium.

In this photograph, taken after much of the scaffolding within the atrium had been removed, the raw concrete framing of the atrium can be seen on the left with the marble cladding of the atrium face seen completed in the centre, the angled grain of the white marble mirrored around the centre line of each face of the atrium. Fixed at the top of the marble is some of the steelwork leading up to the centre of the atrium onto which the cast plaster ribs have yet to be fixed.

Here workers can be glimpsed on scaffold platforms working with temporary lighting to fix in place some of the plaster ribs at the high levels adjacent to the central atrium. This scene replicated the work that took place in many areas of the building as there was a significant amount of detailed plasterwork to assemble and fix in the different ceilings of the Diwan.

Although there are important working rooms within the building, particularly those of the office of the Ruler and the State majlis, the atrium was considered in many ways to be the focus of the building both figuratively and literally, with it being anticipated as being a setting for formal occasions, as has proved to be the case. Many of the elements of the building’s design can be seen in part or whole in this space, the detailing extending out into the rest of the building.

In the first of these three photographs, workers can be seen carrying out work on the marble finish to the central floor area with the aid of temporary lighting and material used to protect their finished work. The photograph was taken looking north with the entrance behind the photographer and the two grand staircases glimpsed on the left and right. The plaster ribs both contain the space while establishing an element of privacy as well as drawing the eye upward to the central feature, the Syrian decorated timber rose with its pendant decorative chandelier, unfortunately out of sight in these two images.

With the work finally completed and the Diwan al-Amiri functioning as intended this second image, taken from a similar viewpoint, is the same space seen with a Head of State being welcomed within the impressive atrium. The third image shows another Head of State being welcomed, the view being approximately at right angles to the first.

The building has two grand staircases. Each is approached by a broad flight of four steps which form the surrounding base for the staircases as well as incorporating fountains below the first landings. Visitors are led up the building on steps which are themselves relatively deep and comfortable to use. In addition to the staircases there are lifts for guests and staff.

As can be seen here, both the ceilings and the walls are decorated with plasterwork, the walls treated with the traditional naqsh work, albeit on a much more extensive scale than in old buildings, and which might be thought here to simulate wallpaper.

On the landings are windows which have stained glass set in traditional patterns. This character and treatment of windows with stained glass also occurs in other parts of the building.

Plasterwork is a significant feature throughout the building not just on walls in the traditional naqsh carved work, but also in the ceilings where interpretations of the traditional carved work have been developed with the patterns generally being of a significantly larger scale as can be seen in this photograph of a ceiling under construction. A workman can be seen right of the middle of the bottom of this photograph, working on the ceiling.

The ribbed lineal design is a feature which runs through much of the building, moving into and around curved features which have both a classical and a feeling for the local traditional work to them. In the lower photograph of these two plaster ceilings, the scale of the majlis ceiling has allowed a different approach. While the central features have a cursive treatment developed from the carved traditions, the area between them has the traditional axe-head design covering it.

For an indication of the scale of this ceiling, note the figure on the bottom left edge of the photograph working on the ceiling.

The building contains a number of lighting fittings which, apart from individual task lighting, loosely fall into two types: background lights which are fixed out of sight and produce functional lighting designed to allow people to more around in safety as well as illuminating wall and ceiling plaster features, and lighting fixtures which are decorative elements of the building. In the main these latter types are bronze and crystal chandeliers and wall sconces.

In this first photograph both types can be seen though the image is not of the finished corridor, the walls having protective material over them while work is being carried out and the ceiling adjacent to the wall still open for access for electrical and air-conditioning work.

This lower photograph is of a larger bronze and crystal chandelier together with the background lighting produced by the plaster cove lighting. The images shows the importance of having hidden light sources producing an even spread of light along their length by the careful design of the fittings. The image also shows the colour of the different types of light source, the colder background lighting with the warmer feature lighting.

Not only was bronze used on lighting fixtures, it was used extensively within and outside the building. This photograph shows a part of a bronze balustrade fixed in place but with protective wrapping while work was proceeding near it. The patterns are a reflection of the traditional patterns found all over the building but in this case they also conform to building regulations in the dimensions of their open elements.

Within the Diwan compound, and at the entrance to the building, there is a porte cochère which provides the traditional way of sheltering those entering and leaving the building to and from a vehicle. But in the case of the Diwan the front of this feature is also a useful setting for greeting guests such as, in this case, a visiting Head of State. The photograph shows H.H. Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani standing with his guest in front of the large bronze gate set at the front of the porte cochère prior to inspecting the Honour Guard drawn up facing them.

The first of this group of three photographs shows how views south-east to the south courtyard of the old building have been opened for it to become an important visual link with the new development. Part of the old Diwan, that facing north across its courtyard can be seen in its original form with both the ground and first floors having open colonnades. Some of the new landscaping combining the old and new buildings can be seen between them partly visible behind the Honour Guard.

While the new Diwan al-Amiri development is connected to the old building internally at the two levels of the old building, there is also a gateway link to its northern courtyard, the part of the old Diwan which accommodated the main staff of the building, and which can be glimpsed behind the Honour Guard in the second of these three photographs with a simple band of naqsh decoration around the doors and flanked by two bronze and crystal wall lighting fittings.

These doors face directly opposite the main entrance to the old Diwan which itself faces due east towards the old Doha suq. In this image, taken of a visiting Head of State’s entourage driving up to the entrance, the new planning of the area bounded by the Corniche on the left, north, side and Abdullah bin Jassim Street on its south, can be seen now with no buildings but landscaped and known as Suq Waqif Park and Garden. The Qatar Central Bank is the building facing six hundred metres away with the glass façade, and the distinctive Clock Tower is on the right.

There are too many items to illustrate on these pages but the next group of photographs show how some of the furnishing items were placed for inspection. This enabled the client and his representatives to assess the design and detailing of every item that would be seen at a distance and, in many cases, would be handled. This next group of images show some of the details of the furniture of the building.

The interior of the building was even more closely related to the traditional architecture of Qatar through the detailing of its interior elements. Carpets, zulij, marble flooring, wooden doors and screens, crystal and brass chandeliers and wall sconces, plaster ceilings and naqsh, furniture, stained glasswork, windows, napery and the like – all were designed with the requirement that they should reflect the traditional design vocabulary of the peninsula and be integrated into the building creating a development which accurately represented the State. There is a significant amount of naqsh work which was carried out by a team of local craftsmen working throughout the project, both within the new building as well as in the rehabilitated traditional buildings which formed a part of the overall development.

These two design elements, respectively around 100mm and 150mm tall, show a little more of the way in which design was approached. The piece on the left was fabricated as a turned plaster element, based on traditional naqsh designs, but destined for use as a feature associated with other elements of the building. The design intent was to bring more three-dimensionality to traditional naqsh features set within the building, pairing it with the more two-dimensional characteristics of traditionally carved naqsh panels. The example on the right was fabricated in Europe from bronze and crystal and was one of the elements used in the design of the range of chandeliers and wall sconces which light the building.

This photograph is of one of the rooms in the Diwan, still under construction, in which a variety of samples were placed for review, testing, possible changes and approval by the client and his representatives. Within the single space it was possible to see elements of the building which would be placed in different rooms and their quality and coherence assessed.

Curtains were hung so that their weight and appearance could be assessed in-situ, and chairs were tested for their construction and comfort as well as their design and appearance with a number of cutaway units produced for inspection and testing as is illustrated by this photograph of a two-seat sofa showing part of its construction and finish.

The next two photographs show examples of large scale curtain tassels that were prototypes of those which would be confirmed, fabricated and put in place to complement the tall curtains in some of the important rooms of the completed building. In the first image, the proportions of the soft tassels to the hard gilded globes was carefully considered for viewing at a distance, and the perforated traditional pattern of the globe on the right gave detailed interest when seen close to, as did the modelling on the globes on the left with a semi-precious blue stone presented in a bezel setting. The colours were tentative but generally it was decided to prefer gold tassels against blue cord, this being in keeping with the colours of the blue and cream carpets and many of the curtains. But, as can be seen in the lower of these two images, other tassels were designed using gold, blue and cream suspended from a braided cream and blue rope, this tassel being not as large nor important as those above.

This photograph shows a few samples of the curtain material side by side for comparison, and features patterns derived from naqsh designs common to the peninsula. As with other furniture designs, the colours of these soft materials are predominately gold, blue and beige though pink was used in other designs, and similar to the pink that can be seen in a photograph below in the edge trim on some of the carpets.

In the photograph of the samples room, three above, the double doors to the room can be seen in the background. This detail, looking into the room through the opened door, shows the extent and significant degree of modelling of the plane of the door based on a limited selection from traditional naqsh carved plaster panels in the architecture of the peninsula. It is significantly different from the decorative treatment of timber doors. It can be seen that different types of wood were incorporated into these doors with a variety of running patterns both covering their face as well as framing the edges of the doors and their handles.

Essentially the scope of the brief defined the degree of two- and three-dimensional character allowed in the detailing of the building, both for its built-in as well as loose elements. This definition of the character of the project can be seen throughout the building in the application of geometrical designs and patterns as non-figurative elements of the building, with a few representational elements allowed, such as in paintings relevant to the peninsula, one of a falcon which is shown here in the office of H.H. The Amir.

In this group of photos above and below, the character of decoration can be seen, particularly in the loose furniture and drapes of the room. The colours of blue and cream are related to the na’in carpet in the centre of the room and which sits on a beige carpet which has a running border predominantly in blue and pink, these colours working well with the maroon of the national flag. This detail of the curtain with its tieback is shown against the maroon of the national flag. Both the curtain and tieback have geometrical patterns based on the traditional patterns found in the traditional architectural vocabulary of the peninsula.

Seating for guests is provided by broad, comfortable, classical European styled chairs with a gilded wood frame covered in a beige on blue ground geomtrical patterning which is designed to match both the curtains as well as elements of traditional dowshek carving within the room, both on the walls as well as on the wooden furniture. The chairs have well-padded arm rests as it is the practice in the Gulf for people to sit with their body propped by an arm on a dowshek, and this permits this practice if required.

Much of the furniture in the rooms of the Diwan have relatively simple designs, both in their basic forms and construction as well as in their decoration. This detail of part of a side table illustrates the simple design of the table and its legs, the latter having a running geometrical design running along them and the front and sides of the table, and the top having a marble panel inlaid with a traditional pattern.

Not all the side tables are as simply designed as this example. The lower of these two photos is a detail of the photograph four above, showing an octagonal table with framed legs and a more intricate patterning, but again all based on traditional geometrical examples. Also visible in the photograph is the running design set into the room’s fitted beige wool carpet.

The Ruler meets Heads of State and other dignitaries in a number of spaces within the building, the settings having different significance in terms of the hierarchy of diplomatic protocol, this photograph illustrating an informal setting, the visiting Head of State here has a translator sitting behind him. As an aside, the Ruler in his own country will require foreign language speakers to speak Arabic or provide a translator for reasons of protocol. This particular setting has the Ruler and guest sitting at right angles to each other with a small table between them. A slightly more formal setting will have them sitting side by side, again with a table between them, such as in a majlis.

This is an image of the front of an important desk within the Diwan. In keeping with the character of decoration within the room and building, the design is solid and has been decorated with simple carved geometrical patterns both as panels as well as edging and corner details. Parts of the design have been elevated by gilding. The overall effect is of a substantial piece of basic furniture, fitting for the purpose of the room and building.

The policy of crafting the building within a traditional vocabulary resulted in a number of original features, many of them designed and fabricated by craftsmen both in their national factories as well as on site. The ceiling of the central atrium, shown above, is a case in point, the geometric timber panels being semi-fabricated in Syria and then assembled and finished in situ by the same team of craftsmen who had fabricated it. This was repeated in many of the larger scale works where site assembly was necessary. In this image, the elevation of one of the sides of the central atrium – with members of the Advisory Council in 2019 standing in front of one of the grand staircases – shows the ribs which extend vertically to become the timber ribs covering this important space. It is a fitting space for the reception of guests to the country.

Here is a different view, slightly off-centre, of the atrium, in this case with H.H. The Amir welcoming a Head of State inside the building, rather than at its entrance. The view across the atrium looks due south, the entrance in front, the two grand staircases on either side. The ribs are evident in drawing the eye up into the top of the atrium, but the wide angle of the camera lens is still unable to show the central decorated timber feature and the pendant chandelier. Though it is difficult to discern, the main structure of the atrium is clad in white marble, as is the floor, though the latter has a decorative and coloured pattern inlaid into it.

It is some time since the building was constructed and occupied, and it is only now that it is possible to see some of the other spaces in the building. The first two images are of the majlis and are intended to give an indication of the scale of the space as well as illustrating how a majlis has its seating formally organised for its traditional purpose, a space for the host to greet and meet his guests.

The first image, above, shows H.H. The Amir sitting and talking with his guest, another Head of State seated on his right. The chairs and tables are carefully arranged to give a degree of emphasis to their rôles as host and guest, with the chairs of their respective entourages spaced slightly closer together. The occupants of each two chairs share a table between them on which, depending upon the circumstances, a range of items will be placed – tissue boxes and drinks in the main but nowadays perhaps mobiles and occasionally recording devices if a meeting is to be formal.

In this second photograph the size of the majlis can be seen with its seating for a little over a hundred people in the normal single bank of peripheral setting. On some occasions, and when circumstances dictate, it is possible for the majlis to accommodate at least one and up to three sides double-loaded with a second or third bank of chairs for the additional guests, though this is certainly not the norm. As an example, the third photograph shows double rows at the short ends of the majlis and triple rows facing the host.

In all four images the scale of the majlis can be seen with the main design features of the building on display in this one space: the dramatic ceiling modelling with its pendant bronze and crystal chandeliers replicated on the walls with matching sconces, the articulated window arches and swagged curtains, the walls with naqsh carving and the sculpted and modelled carpet with three Persian carpets sitting in its centre.

The small tables carry both covered water glasses as well as small trays of dates. In the second image it is just possible to see that alternate tables also have a posy of flowers, a traditional introduction of perfumes which accompany those of the coffee, mint tea and the a’oud brought in for special occasions.

And the majlis is also being used as a setting for presentations or addresses to be made to the Ruler with, as is illustrated in this fourth image, a lectern being brought in and the presenter facing the Ruler across the floor of the majlis with guests in the traditional peripheral arrangement.

As a final example of the design of internal rooms of the Diwan, this image is of the formal conference room. The design of the walls of the room is based on the trabeated construction of traditional buildings in the peninsula, and the table is designed in the style found all through the building with an inlaid pattern of marble let into its top face. The table was designed on two levels into which standard communication and informational systems are incorporated in order that simultaneous translation is available to both hosts and guests. Here, the Ruler on the right sits in the standard protocol arrangement at the centre of the table and directly opposite a visiting Head of State, each flanked by their appropriate staff.

More has been written on the development, particularly of its exterior, on another page.

more to be written…

Development of al-’Aliya

In order to begin the process of creating and improving a wide variety of activities in the Qatar peninsula, the New District of Doha was identified as a setting for a number of different types of activities that might be suitable for this area, given its relationship both with Doha as well as with the north of the country. It was seen as being particularly well suited to the development of recreational activities.

A number of studies were carried out, one of them being by Kenzo Tange and Urtec. This produced four alternative schemes for a resort development to be situated on jazeerat al-’Aliya, the island located immediately to the north of jazeerat al-Safliya.

Al-’Aliya was determined as being the setting for this particular study within the NDOD, in preference to the nearer island of al-Safliya, in order to draw recreational activities further away from Doha and avoid concentrating such facilities within, or even close to, Doha. Bear in mind that at this point in time, 1977, al-’Aliyah was considered to be a significant distance from intended development in the NDOD as was, for instance, the university.

Designed to be constructed in three phases the resort project suggested an interesting schedule of uses for its time:

| lagoon | beach | shelter for swimmers | locker and shower room | |

| floating cafeteria | marina | swimming pool | tennis courts | |

| squash courts | athletic club | central plaza | botanical garden | |

| fountain | cascade | pedestrian mall | park | |

| multi-purpose hall | exhibition hall | art gallery | aquarium | |

| marine museum | bungalows | shops | mosque | |

| restaurant | cafeteria | heliport | moving sidewalk | |

| administration office | maintenance office | seawater distillation plant | sewage & garbage disposal | |

| water supply installation | energy supply installation | |||

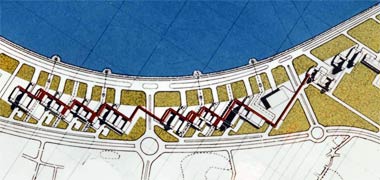

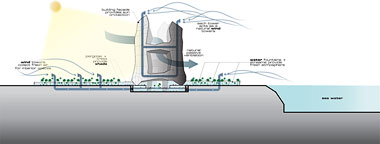

Although the improvement of recreational resources was deemed to be a priority, for a number of reasons this particular project was put on hold and never realised. The lower illustration of the two above is of one of the four Tange and Urtec schemes that were developed for the island.

The Tower

As was mentioned in the note above on the Corniche, one of the design elements intended as an integral part both of the Corniche as well as the urban design of Grand Hamad, was a strong vertical element. It was intended that this would form the northern focus of Grand Hamad as well as identify the location of the Doha’s suq from the Corniche, in a sense balancing the Hotel and Conference Centre that marks the end of the New District of Doha, approximately 2.8 kilometres directly across the West Bay from the tower.

One of the factors that would determine its location was the location of the three small reefs, illustrated above, north of the jetty which, it had transpired, would be difficult to remove at a reasonable cost, but which might form a suitable base for a tall structure such as a tower. This sketch plan illustrates the organisation of the jetty on which the tower would be located with parking at its base together with a small number of spaces reserved for marine craft that would move people around the bay.

As can be seen from this illustration which shows a photograph of the model set between elevational and perspective sketches, the tower itself was envisioned as a pair of hyperbolic parabaloid structures, both standing on end with the accommodation and vertical access elements of viewing platforms and restaurants set between them. For a number of reasons, this project also did not proceed though the perceived need for a visual focus within the bay remained. Another solution considered was a tall water jet, similar to that in Lake Geneva which would project water to a height of 140 metres. Today there is an island in the middle of West Bay that provides a less dramatic focus.

The Senior Staff housing project

In many ways one of the most important projects that was initiated for the New District of Doha was the provision of housing for government Senior Staff.Its importance was that it encouraged the design of a better standard of house, improved standards of construction were achieved, it brought a cadre of young Qatari professionals into the process of design and construction, and it required closer cooperation between government departments than had previously been the practice. One of the first, and larger, houses is shown here.

This aerial photograph is of a part of one of the earlier areas of Senior Staff housing within the NDOD. This was a novel type of design for Qatar, both in its planning and design. The photograph gives an indication of the character of the layout with its primary and secondary traffic circulation or distribution system leading to cul-de-sac groupings, a character of development dealt with elsewhere in more detail. It is interesting to observe the amount of development on the lots, but the most important contribution made by the housing was the improvements it brought to housing generally throughout the country by raising development standards.