a collection of notes on areas of personal interest

- Introduction

- Arabic / Islamic design

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 01

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 02

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 03

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 04

- Islamic architecture

- Islamic urban design 01

- Islamic urban design 02

- Islamic urban design 03

- Islamic urban design 04

- Islamic urban design 05

- Arabic / Islamic gardens

- Gulf architecture 01

- Gulf architecture 02

- Gulf architecture 03

- Gulf architecture 04

- Gulf architecture 05

- Gulf architecture 06

- Gulf architecture 07

- Gulf architecture 08

- Infrastructure development

- The building industry

- Environmental control

- Perception

- The household on its lot

- A new approach – conceptual

- A new approach – principles

- A new approach – details

- Al Salata al jadida

- Public housing

- Expatriate housing study

- Apartment housing

- Pressures for change

- The State’s administration

- Society 01

- Society 02

- Society 03

- Society 04

- Society 05

- Society 06

- History of the peninsula

- Geography

- Planning 01

- Planning 02

- Population

- Traditional boats

- Boat types

- Old Qatar 01

- Old Qatar 02

- Security

- Protection

- Design brief

- Design elements

- Building regulations

- Glossary

- Glossary addendum

- References

- References addendum

- Links to other sites

A brief note on Islamic architecture and its relevance to Qatar

Research and discussions with those with expertise in Islamic architecture suggest a variety of ways in which this area of the built infrastructure might be best considered and defined. However we decide upon our definitions, there appear to be certain characteristics of buildings which must obtain when arriving at a description or definition of Islamic architecture. By extension much of this will relate to the traditional architecture of Qatar.

For the purposes of this study I propose to use the following working definitions, suggesting that Islamic architecture appears to have five characteristics:

- the promotion of internal over external development,

- articulation through the use of light,

- a relationship with natural elements,

- the articulation of internal spaces which reflect the construction techniques – particularly of the arch and dome – and incorporate non-representational decoration as an enlivening feature, and,

- a strict hierarchical attitude to privacy.

Traditional Gulf architecture, in response to the general economic climate of the area, was a less sophisticated form of Islamic architecture characterised by the use of more prosaic building materials and an emphasis on trabeated construction forms. Its vocabulary of building elements responded directly to the need for environmental controls, security and shelter.

Qatari architecture, while similar to that in other Gulf States – and, of course, Iran – is less sophisticated, and of smaller scale with more robust decoration. Of particular note is the lack of extant wind towers – the single example in Doha is all that remains in the whole of Qatar – although there was once a number of them, particularly in Al Wakrah. In the same way it is argued that there may not be a single Islamic architecture, it might be said that there is no archetypal Islamic town other than a town evolved through development by Muslims. However, there are still characteristics which, deriving from Islamic principles based on earlier Greek and Roman examples particularly, have given towns certain attributes. It is in this sense that there can be thought to be an Islamic town and urban form.

As Islam spread its basic tenets were assimilated by the inhabitants of the countries which now came under its authority. At first this had little influence on the towns and cities as they were already established; no major building programmes were required to house an expanded population, and no new cultural or artistic requirements were needed. But, with time and changing moraes, the Muslim populations built, developed or re-established important centres with an Islamic character of their own. This character was noticeable and differed in many respects from the earlier developed cities established by the Greeks and Romans.

Let me begin with a question. What do you think the link is between these two photographs which illustrate very different examples of Islamic / Arabic design? And, for a minute, let’s refer to them as Islamic / Arabic design even though many would argue that only the lower one might be described as such. I should also state here that I’ll be writing about Islamic and Arabic architecture later on.

I’ve deliberately selected two images that don’t, at first inspection, appear to be classical Islamic / Arabic designs. The first of these two photographs is of a part of the atrium in Qatar’s Doha Sheraton hotel, a building designed in an ‘Islamic’ fashion, the style relying, some would argue perhaps, mainly on the use of applied pattern. The photograph below it is of a pedestrian street in Granada, Andalusia, and is an illustration of a typical street scene established by the Moors prior to their leaving in 1492.

The link, as you’ve probably guessed, is that they both might be thought of as being a form of Islamic / Arabic architecture, but neither are what we immediately think of as that. The preponderance of examples that come to mind are those we see in the longer-settled Islamic countries on the Mediterranean littoral ranging from Morocco in the west to Turkey in the north, together with Iraq, Iran and the Arabian peninsula states, the latter sometimes referred to as the Persian Gulf states.

When I first selected these two photographs it was with the intention of making an argument for the lower example at the expense of the top one. Since then I’ve been thinking about the subject of Islamic / Arabic design as I’ve been researching and writing about traditional Qatari architecture. There seem to me to be two ways to approach this building: one as an example of an introverted traditional building, and one as an example of a building type, a funduq, or hotel.

And what characterises these images? There are a number that immediately come to mind when thinking of Islamic architecture. Here, to the right, is an internal view of the Mezquita in Cordoba, Andalusia, Spain. Established by the Moors it has a church added in its centre following the Christians’ removing seven hundred years of Moorish rule in 1236 as part of the long process known as the reconquista which saw their complete removal in 1492 from the Iberian peninsula.

Here, below left, the Sheikh Lutfallah mosque and, below right, the Friday mosque, both in Isfahan perhaps more faithfully reflect a Western view of ‘typical’ Islamic architecture. Above them are details of the the Lutfallah mosque showing glazed tiling on the left and part of the muqarnas of the main iwaan on the right. Yet these are both religious buildings.

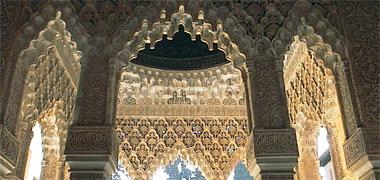

These are examples of the kind of Islamic architecture we think of without any real understanding of their context; neither the circumstances that brought them into being, nor their meaning today. We tend to see them as symbols representing both Islamic architecture and our slight understanding of Islam. One of the most important examples in this regard is the Alhambra complex in Granada, Andalusia, Spain. The Alhambra contains some of the most popular images that characterise our view of Islamic architecture, images that have populated the collective Western understanding since the nineteenth century when it was popularised by the American writer and traveller, Washington Irving.

The Alhambra is a beautiful example of its sort and stands on a dramatic setting, but it is relatively small in comparison with other Islamic developments. Nevertheless there is within its loose arrangements of rooms and corridors a series of beautifully organised spaces with surface decoration in tilework and carved plasterwork, the former exhibiting the complete range of tiling possibilities.

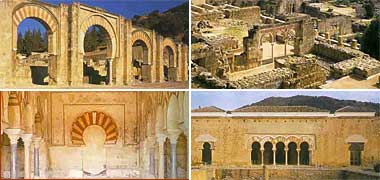

Two examples are worth mentioning here though there is virtually nothing left of them. They were both both large complexes and, particularly the latter, were probably the most important of their kind in the Middle East and Europe combined, in their time.

The first was Medinat al Zahra, a few kilometres outside Cordoba in Andalusia, Spain. The second was the development by Moulay Ismail in Meknes, Morocco.

Medinat al Zahra was developed by Abdulrahman III who ruled Cordoba between 912 and 961, and Al Hakem who ruled between 961 and 976. Constructed as a series of three descending terraces, the ruler’s palace occupied the highest level, government offices and important personnel on the middle, and the town with its houses, commercial and industrial area were set on the lowest terrace. It was destroyed in 1010 AD by a Berber army supporting the Kingdom of Taif. In its day Medinat al Zahra was recognised as a great centre of civilisation and medical innovation as well as being beautifully designed and decorated. Regrettably little is left to see, much of the city has not been excavated and there is now concern for modern development encroaching on the site. Although mostly a later development by two hundred years, the Alhambra complex of Granada can give us a feeling for how Medinat al Zahra might have appeared in terms of its organisation and detailing.

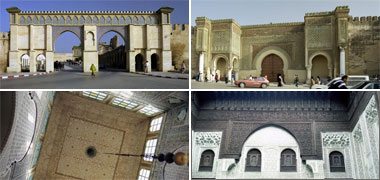

The late seventeenth and early eighteenth century saw the development in Morocco of a massive project by Moulay Ismail. At Meknes, with considerable reliance on European slave labour, he built a very large complex to house him and the support he relied upon. Moulay Ismail thought little of the European rulers other than the French King, but even the latter’s palaces were nothing compared with that at Meknes.

Fez, which had been the paramount city in sixteenth century Morocco, had fallen into dereliction by the middle of the seventeenth century. The Al Badi palace of Marrakech was then considered to be the most beautiful in Morocco, but Moulay Ismail decided to produce something far grander than at both Marrakech and Fez, and had Al Badi demolished. The city he built at Meknes was surrounded by fifteen miles of walls with twenty main gates, two of which can be seen above. Evidence from visitors is that it was finely and richly decorated. What is left to be seen in Meknes pays testament to the expenditure on construction and decoration made by him, though it can’t be said that his rule was accompanied by patronage of the arts and sciences as was the case in many other areas of the Islamic world. Moulay Ismail died in 1727, the city being further developed by his son and grandson, but being devastated by the earthquake of 1755.

It is a pity that we are unable to see Moulay Ismail’s Meknes today. There is a large body of contemporary evidence witnessing its scale, construction, material and detailing from which we know that it must have been one of the grandest in the Islamic/Arabic world. The scale and extent of it appeared to have astonished all those who visited but, more than that, the sequence of spaces and their different contents made it a setting for a sybaritic life – perhaps more so had it not been dominated by such a cruel ruler.

It is also regrettable that we don’t know as much about the concomitant urban development that housed and provided for the people supporting the palace as we do about the palace itself. The palace represented a character of urban development typifying north African strongholds with its massive walled protection. The walks, apartments and courtyards were heavily decorated with arabesque carved plasterwork and glazed tiles, the finishing work carried out by craftsmen from Andalusia. It contained landscaped gardens, belvederes, parterres and a range of landscaping elements designed to enrich the souls of those living – and impress those visiting – the palace. There were a number of gardens, even one built to resemble the hanging gardens of Babylon. Excavated twenty metres into the ground the garden was surrounded by cypress trees and had a kilometre of terraced walkway above it covered in vines and hanging plants. In addition to the elements designed to elevate the senses the Palace also contained workshops, magazines and other spaces designed to support Moulay Ismail as well as provide and maintain his armies with the equipment to fight.

The Alhambra in Granada, Spain, gives us only a small hint of what this might have been like, and other developments in the Arabic world show how different countries established their own characters. But all these were far richer than anything that was built in the Persian/Arabian Gulf.

Waqf

Traditionally, a number of buildings in Islamic countries were constructed under a waqf, or charitable foundation. The practice pre-dates Islam but endowments are associated with Islam and were an important institution in the development of a number of buildings and institutions.

In many countries, both pre- and post Islam, property could not be passed on to heirs on the death of the owner, but reverted to the Ruler. By enacting a waqf on a property, the benefits from that property were permitted to be used for charitable works, most usually for the construction and running of works for public benefit. An additional benefit was that it relieved that property from state taxes. With reference to Islam, public benefits usually meant mosques, madrassat or Islamic schools, fountains and bath houses. A waqf would usually be associated with farms and arable land but, in some countries, was based on bakeries and similar commercial facilities. The essential requirement for the waqf was that it should be based on non-perishable items. Most usually this meant land and buildings, but it could also be used on items such as books, equipment and machinery.

Initially it appears that the waqf was enacted both for altruistic purposes – the person enacting it obtaining benefit in the next world – and for his family’s benefit in the longer term, usually members of the family being appointed managers of the waqf in perpetuity. The family was thus able to draw benefit from the continuing operation of the waqf as well as being associated with a public good.

Waqf can be seen to be giving good to the local community but there was also a form of waqf that can be seen as philanthropic, producing good for those in some form of need, usually the poor, but also the community at large. In this latter sense the philanthropy should be seen in its wider sense, covering not just the socio-economic aspects of the community, but extending to animals and the environment, an important aspect of Islam that has resonance in arguments I make elsewhere about the essential relationship of the house with its surroundings, the owner and his relationship with the community.

There is also a form of waqf that gives benefits to heirs and descendants, but this is outside the scope of this note.

An extension of the development of waqf is that there was a gradual increase in the lands under its control, and a consequential increase in its importance in religious and philanthropic terms. The waqf is still an important operation in the running of mosques and religious schools and most Islamic states have official organisations established for the administration of awaqf. There is, however, an obvious relationship between the growing power of States, their incomes and relationships with their citizens, and the nature and operation of waqf. This is a socio-political area that must remain in balance, but it can be seen that there are pressures arising from the extent to which foreign influences are altering the character of the State and its citizens.

The mosque of the Prophet

When the Prophet lived in Mecca he held prayers for his followers at the Ka’ba, the structure which was used in pre-Islamic worship and, according to Islamic belief, was constructed by Abraham. On the Prophet’s taking Mecca in 630AD, the Ka’ba was converted into a masjid and expanded to become the masjid al Haram, the holiest place in Islam.

In essence musajid are derived from the first place of worship, that which the Prophet built adjacent to his home on his arrival in Madina in 622AD. Although he started the simple masjid al Qubaa’ as soon as he arrived, almost immediately he began construction of the masjid al Nabawi which, today, is the second most holy place in Islam, with the masjid al Aqsa in Jerusalem as the third.

Oriented north towards Jerusalem, the Prophet’s mosque, later named the masjid al Nabawi, was a relatively simple building, about thirty by thirty-five metres. It was constructed of palm trunks and mud walls which incorporated entrance doors from the south – bab rahmah, east – bab al Nisa’ and west – bab al Jibril.

Later, following the revelations within the surat al baqara, the mosque was oriented to face south towards the masjid al Haram at Mecca.

It is unlikely that the manara, or minaret was established at this time. Four were added later to the masjid when, in 707AD, the Umayyad Caliph al-Walid demolished the enlarged masjid. With the larger Muslim population there would have been a greater reason to call the adhan from a high vantage point. Eventually it was called from a manara when there appears to have been concern to ensure all were able to hear it. The form of the adhan was established in the Prophet’s time, and was called from the door of the masjid.

Mosque design

As I noted on the Gulf architecture pages, the traditional architecture of Qatar used to be much simpler than the architecture I am generally describing on these pages. This is particularly true of the masaajid, for they had an honesty created through simplicity of design which makes them models of their purpose and sets them apart from the architecture which is being created nowadays. Increased wealth can bring not only greater opportunities, but greater responsibility. One of the purposes of these notes is to set down some of the possibilities inherent in the intrinsic design qualities of Islamic architecture in its wider setting.

The masjid is one of the chief elements of Islamic urban design; some believe it to be the most important; the bayt and the suq would be the second and third elements. In some parts of the Islamic world, the Ruler’s palace complex and fort might constitute the fourth and fifth, and maqbarat, while not a building type, a sixth urban feature. Qatar contains all these elements but, in many ways, the byoot and masajid are the most important elements, the anonymity of the byoot acting as a foil for the punctuation of the urban landscape by the masajid, particularly their manara.

The masjid originally had no open space associated with it though this developed as a reflection of the house of the Prophet, described above, and below. The sahn, or internal courtyard, became a feature of masajid but this did not affect the external relationship with the urban scene where the masjid formed a fairly tight relationship with, usually, those elements of the suq which related most closely to the purpose of the masjid.

With time this physical relationship altered, most notably in the northern Islamic world where a ziyada developed as an enclosure on three sides of the masjid, but not the side incorporating the qibla. This characteristic did not provide the type of open space found elsewhere in the world at the entrance to the place of worship, where goods might be sold and public events held – and which also served as a porte cochèreor space for a visual introduction to the masjid. Instead the sahn became the space for meeting but, obviously, without any commercial association. It was, however, related in some parts of the Islamic world to scholarly pursuits associated with Islam as well as those of medicine and charitable work.

The point to make is that there was little space provided around the masjid from which to appreciate it as a work of architecture – this very much in contradistinction to the design of Christian churches and cathedrals. What was distinctive was the manara which developed as a position from which to summon the faithful to prayer and, in doing so, increased in height. This is likely to be not just a reflection of the need to be able to reach Muslims in their houses some way away, but also of religious imperative.

This proximity of masjid to bayt has been central to the relationship between Muslims in that it produces a more intimate bond between those who live around masajid, and their devotional practices both outside and within them. The small masjid has always been an integral element of the fabric of Islamic urban developments, both from a spiritual as well as religious point of view, and it is important that this continues.

But times are changing. Small masajid are becoming larger, a reflection both of the provision for a growing population – a standard of one masjid to seventy byoot used to be a standard, though I don’t know if this is still used – and the increasing affluence of the State. As they become larger, and as they are planned for within new residential areas, the relationship of their walls to adjacent housing has become looser. Adjacent housing is no longer as it used to be but consists of villat, as they are termed, detached houses sitting in the centre of a large plot surrounded by a peripheral wall.

Perhaps more important in the physical relationship between masjid and byoot are the changes there have been with regard to distances between the two due to the size of the new housing plots, as well as the transport available. At its simplest, people have further to walk, and the density of use on the pedestrian systems are much lighter. Because of this there are more people who use vehicles to take them to the masjid. To some extent this might be because they are not coming straight from their home but from a more distant location. However, the corollary to this is that there is now the need for, and provision of, parking space adjacent to each masjid.

So, no longer is the masjid tightly bound by the urban fabric of the byoot which it serves; nowadays masajid tend to be designed and constructed as architectural objects to be viewed in the round. In this they are similar to the juma’amasajid which Dogan Kuban is quoted as suggesting as being more representative for their cultural and aesthetic experience rather than being related to the devotional practice of ordinary people. If this is so, it suggests that the present practice of masjid design is not serving the ordinary people of the peninsula as well as traditional masajid did. It also follows that this is not in accordance with the premises of wahhabi practices.

There is no formal requirement for Muslims to pray in a mosque or masjid other than on Friday when they are enjoined to pray together – 62.009 and 62.010:

O ye who believe! When the call is heard for the prayer of the day of congregation, haste unto remembrance of Allah and leave your trading. That is better for you if ye did but know.

And when the prayer is ended, then disperse in the land and seek of Allah's bounty, and remember Allah much, that ye may be successful.

Otherwise the only requirement is that Muslims should pray, when it is required, and then where they find themselves. In praying, that place is elevated to the status of a masjid, the root of the word meaning a place where one prostrates oneself.

Although Islam is a religion which has a communal aspect and encourages communal prayer, especially on the holy day, Friday, at the juma’a mosque, the essence of prayer can be seen in the way in which Muslims carry out their more informal, daily prayer.

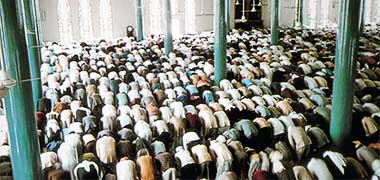

At prayer, a Muslim enjoys a personal relationship with God whether or not he is in a masjid. It is important to remember that, even when he is in a masjid, there is no hierarchy involved. Everybody is equal. There are no clergy, only an individual selected to lead the prayers and who commonly kneels at the front of the congregation. It is imperative that the musalla of the masjid is designed to reflect this.

The mosque in concept

But first there is something that has to be explained to those unfamiliar with Islam and its worship. Many of the readers of these notes may be familiar with Christian churches, particularly the traditional models that are characterised by the linear plan of the nave – usually divided by an aisle that functions both for circulation and ceremonial process – and which is focussed on an altar, the central design feature of worship where the holiest items are set and used in a manner depending on the variety of religion practised. In this sense the altar occupies the holiest part of the church and its immediate surround is the most important area in which prayer might be made, though it has to be said this is rare, most prayer taking place within the body of the nave.

This linear arrangement has been altered in recent years in order to reflect changes in liturgy as well as in an attempt to entice a dwindling church-going population. This has brought worshippers closer to a central altar, some church designs being based on a circular plan. This focus on a closer altar and the priest or vicar carrying out the service, is a common feature of these churches. Regardless of whether the place of worship is based on a lineal or circular plan, the focus remains the altar.

By contrast masaajid are conceptually very different. Wherever in the world they are, Muslims face the ka’ba in Mecca when they pray. There is no local altar in a masjid, although there is a mihrab – usually centrally located in the qibla wall – with associated minbar to its right when faced by the congregation, where the person leading the prayers will sit to lead the prayers and lecture them on issues of importance. The purpose of the mihrab is to mark the importance of the qibla wall. It is not the equivalent of an altar.

There are no seats; those praying will stand and kneel during prayer with there usually being a carpet with lines or individual carpets set out to mark the places for the faithful to stand. The most important element is the qibla wall with its central mihrab facing the ka’ba and giving the direction of prayer. Overflow of a musalla is usually located in the finaa’ that lies behind the musalla and, if this is insufficient, then the faithfull will stand to the side of the masjid, out of sight of the musalla, but facing in the same direction as those inside.

Within each Muslim there is an understanding of the overall imperatives of Islam together with an intuitive feeling for the ummah, the collective of all Muslims in the world. This is not just a religious issue, it also has a socio-political dimension that will be discussed elsewhere. This basic comprehension, allied with the requirement to pray five times a day at specific times and with the posture in prayer dictated precisely, creates a very strong supranational force where, as Raban writes,

…the entire ummah goes down on its knees in a never-ending wave of synchronised prayer, and the believers can be seen as the moving parts of a universal Islamic chronometer.

The relevance of this to the design of masaajid is in understanding that the form of a masjid is, in a very real sense, an enclosure for only a part of this ummah, that the qibla wall is important to directing prayers, but that the side walls of the masjid are, in a sense, arbitrary in their placement. Their real importance is in guiding the faithful physically and psychologically into and within the musalla, the optimal place of prayer.

From this there is an argument that masaajid should not be seen as objects in the round, and that there should be more emphasis given to the qibla wall, musalla and finaa’ along with those spaces that guide the faithful to the musalla in a sequence producing an increasing focus on the imminent prayers.

At its simplest, and apart from seating, the difference between masaajid and churches is that the long qibla wall of masaajid is set at right angles compared with naves of churches, and that the focus in a church is within the church, whereas the far-off ka’ba is really the focus of a masjid.

Informal prayer

When Muslims pray within a space in an urban setting they tend to put down a sajada or prayer mat which, commonly, is a woven mat on which there is a printed pattern. In some households a small Persian carpet might be used and many of them are woven with a pattern which identifies a top and a bottom to it. When it is time to pray, the sajada is unrolled, oriented towards Mecca, and the prayers carried out.

Where there are more than one person praying it is common for one of them to lead the prayers, standing in front of the others who will, if it is a small number of them, and the space permits, stand shoulder to shoulder behind the leader. Each is likely to use a sajada and they will all be oriented towards Mecca. Within offices and the home there is unlikely to be a qibla or its equivalent, but the direction of Mecca will be known and orientation made automatically. In some offices there are rooms set aside for prayer and, in them, the direction of Mecca is marked, often by the manner in which the carpet is laid.

In the desert there is a slightly different procedure. Although prayer mats might be used, a line is usually drawn in the sand to represent the qibla, and the mihrab is often shown as a small arch drawn in the centre of the line. In some areas where badu stay for a little while, a low wall, constructed of loose desert stones, is constructed in the same form, similar to the sketch below.

Islam and mosque design

Although the wahhabi sunni tradition eschews elaborate design, it is masajid which seem to typify the view many people have of Islamic design; and it is notable that it is the older, more highly decorated masajid that seem to catch the imagination of both laymen and professionals.

Elsewhere I have argued that it is domestic architecture that is more representative of true Islamic design, and that there is an indeterminacy about these buildings which characterises Islamic architecture. But, as I have noted, much of the perceptions of Islamic architecture has to do with the design of masajid. So, what are the requirements of masjid design?

Functional requirements

The mosque or masjid is a place for prayer but, for those unfamiliar with them, I should first note what it is not. Unlike a church, a masjid is not used for weddings, funerals, singing – other than formal recitation of the Holy Quran, this all to be checked as I have seen references to weddings in the early days.

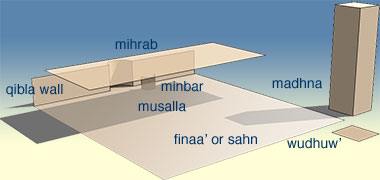

Over time there seems to have been much discussion about the requirements for the design of mosques. This, of course, relates to prayer; and the requirements for congregational prayer are relatively simple to define having changed little over time. The main two components for this is that there should be:

- an area for prayer, musalla, and a

- device, mihrab, on the qibla wall, marking the direction of Mecca, the point to which the whole of the Muslim world turn in prayer.

These are the two functional requirements for prayer and the design of a mosque should reflect them.

To these two might be added a third element, the

- manara, or minaret, from which the call to prayer would be made.

Some state that these are the three necessary elements of a mosque; others state that a:

- finaa’, a congregational area or courtyard,

is necessary as this has been a feature of the earliest masjid. In addition to these there is the need for:

- a minbar, the pulpit from which sermons are made before Friday prayers,

- wudhuw’, an area for the necessary ablutions before prayer and, even, a

- sabil, or ablution fountain,

a feature in many older masajid.

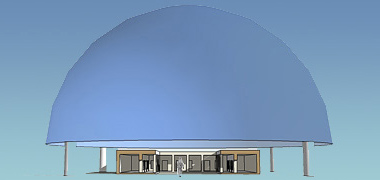

This diagram notionally illustrates these elements necessary for worship associated with a masjid. Although the original masjid built by the Prophet was almost square, I have shown the salah as being rectangular as from observation Muslims prefer to line up, parallel with the qibla wall – whether it’s there or not – behind the person leading their prayers rather than forming a more square arrangement. The manara i have illustrated as a tower, though the original call to prayer was carried out from the roof of the building.

This photograph illustrates the old masjid at al-Dhakhira in the north of the country. The architectural layout of the masjid is clearly organised and reflects the diagram above. There is even a difference in height between the finaa’ and the wudhuw’ which is established at the lower level. There seems to be no reason for this in terms of the natural ground levels on which the masjid has been constructed, so it must have been a deliberate decision to separate them in this way. Why, I don’t know.

Essentially, these are the functional requirements for prayer; they form the quantitative elements for a masjid, though the need for the manara is debatable, as might be the finaa’. I will come back to these elements later as I shall have to for the use of a dome in masjid architecture, and the minbar.

The minbar

One other feature was developed in this early masjid, and that was a minbar. It was the custom of the Prophet to give his sermons from the end of the masjid and, in 628AD, this was developed into the installation of a three-stepped pulpit or minbar adjacent to the mihrab from which there would have been better visibility to an enlarged congregation.

Generally the minbar is located immediately to the right of the mihrab as seen by those praying. The top photograph illustrates the simple arrangement in a ruined mosque at Ruwais where the minbar and mihrab are located almost as a combined design element for lack of space. Here I believe the minbar does not have a raised floor level: normally there would be three steps. You can also see in both these photographs that the mihrab contains a window which is not a usual feature of masjid design. As an aside, it is worth noting the simplicity of the masjid with its conical manara, rectilinear salah and finaa’, and with the only decoration being the elements added to reduce the span of the beams, which can be seen in the photograph at the head of this section.

The courtyard

The importance of the Prophet’s house was that it was used not just for the accommodation of him and his family. It was also used by others both living there as well as using its common spaces for a number of different functions relating to the group’s communal, political, judicial, medical and educational activities. As such the finaa’ was an essential element of the masjid, catering for most if not all of the public spatial needs of the community that were not taken by the salah.

I have written elsewhere about the way in which Muslim society is informed by and dependent upon the Holy Quran. It is both the basis for religious belief as well as the social code upon which individuals’ actions are based and governed. In particular, Islam is a communal religion, one in which each Muslim enjoys the benefits of society through his or her interaction with that society. In their public appearances each represents the family to which they belong and, in their public activities they operate individually and collectively. The finaa’ was the setting in which much of this interaction was carried out, where Muslims were able to operate in their own public forum.

But, in addition to the socio-cultural aspects of the finaa’, there is another aspect that should be mentioned. The finaa’ is an intermediary space between the public spaces of the urban environment and the spiritual space of the salah. As such it helps to isolate the sounds of the urban environment while encouraging the psychological process of preparation for prayers. It helps those coming to pray by acting as a staging area before entering the salah, particularly when associated with the wudhuw’ where the beginning of the process of prayer might be argued to start. The finaa’ has, in this case, a therapeutic effect. Although this would be true at a psychological level of the design of masajid generally, in a successful design, this would assist the process by which a ritualistic exercise becomes true prayer.

Functions change with time but the preparation function is still required. Even without this, the finaa’ still may have an importance to the life of Muslims. Not only is it an overflow area for the salah, it is still an area where they can meet to discuss matters informally or, when associated with functions such as offices, religious school or a medical facility, it might enjoy a more formal function.

The prayer area

The salah is, in many respects, the heart of the masjid. At its simplest, it is the space where the congregation line up behind their imaam and parallel with the qibla to say their prayers every day of the week and to receive the sermon, khutbah, delivered from the minbar by the khateeb or imaam before the Friday dhuhr prayers. There is no furniture in it, no seats or pews as there usually are in churches.

It is an area for men, there being considerable debate as to whether and how women should be able to pray in masajid. In some masajid women have an area set aside for them, usually on the mezzanine, and in some they may pray together to the side of the men. In both cases there is physical separation. What seems to be forbidden is for them to stand shoulder to shoulder with men. In the West there have been demonstrations by women at their not being permitted, by men, to even enter a masjid.

The essential feature of the salah is that it should be established parallel to the qibla wall which marks the direction of the masjid al Haram at Mecca.

Other than that it should be level, comfortable and hygienic with minimal design distraction and a good line of sight for all to the minbar and mihrab. Where there is the possibility, decoration with Islamic decoration and quotations from the Holy Quran are permitted if not expected in order to assist those praying to focus on the reason for their being there.

The direction of prayer

When a masjid is established, an official will ensure that it faces the correct direction by the use of a special compass marked out and ratified for that purpose. As I mentioned above, although prayer was originally made towards Jerusalem, following the revelations of the surat al baqara, prayer is made towards the holiest of shrines in Islam, the masjid al Haram at Mecca.

In terms of the building of a masjid this direction is marked by the qibla which runs at right angles to the direction of Mecca and is the focus for prayer.

At some point on the qibla wall, usually the centre, there will be the mihrab, though on some masajid there are more than one.

The mihrab is usually formed as a recess in the qibla wall, the purpose of the mihrab being to mark the direction of Mecca and to act as a focus for prayer. It is also used as a place to stand by the khateeb or imaam when leading prayers.

Ablutions

Cleanliness is very important in the state of readiness for prayer and, therefore of the operation of the masjid. Before prayer, Muslims are required to wash in a specific manner. The form of the ritual differs slightly between sunni and shi’a, but the purpose is the same – to prepare both the body and mind for prayer, and the means of providing the facilities is also the same.

Traditionally wudhuw’ was provided as a pool served by a fountain or water feature, sabil, preferably with running water. This was often elaborated into a central feature of the finaa’, or entrance courtyard. More commonly, today, the wudhuw’ is a more functional area and is associated with other lavatory functions as can be seen here in this typical provision for wudhuw’ at the entrance to one of the masaajid in the centre of Doha. The essential requirements are a place to sit and individual taps for those washing.

The important feature is that the water should be running in order that the cleansing can be carried out properly. But there is another effect that the running water has, and that is of calming and is another step in the psychological process of preparation for the salat.

Technically the provision for wudhuw’ requires a place to sit in order to be able to wash, in order, the hands, mouth, face, nose, arms, forehead and hair, ears and feet, this ritual being carried out three times. The space in which this is carried out should be suited to its purpose and not cramped, and designed in such a way as to ensure water is not carried out of the space.

Although this photograph shows a high quality ablution area, it illustrates the basic arrangement commonly found in most modern mosques. There are seats or a bench in front of which is a trough leading to a drain, and taps over the trough. This particular design is carefully detailed. In less expensive installations the area is commonly tiled with the taps tending to be left on most of the time while there are people wishing to wash.

As I mentioned above, one of the purposes of wudhuw’ is to prepare for prayers and it is important for this to be a contemplative as well as a functional area. Good design can help this process, bearing in mind that the hard surfaces and movement of those passing through tend to have a detracting effect on the psychological process of wudhuw’.

There is a little more written about washing, this time in the context of the house, on the page that looks at the house on its lot.

The minaret or manaraor mi’dhana

The purpose of a manara or mi’dhana, or minaret, was to provide a good location from which the mu’adhin could call the faithful to prayer. The manara is often asserted to be a necessary element of a masjid, yet it is not. As I mentioned earlier, the first masjid did not have a manara, the call to prayer being made from the door of the masjid.

With time and an increasing number of Muslims needing to know when to come to pray, the manara became an increasingly important element of masjid design enabling the call to prayer to be made effectively. In fact there are two calls to prayer, the first being made in order to enable those living farther away to begin their walk to the masjid.

The use of the top of the manara as a position from which the mu’adhin called the neighbourhood to pray, continued in the Gulf into the middle of the last century, but the advent of sound equipment enabled loudspeakers to be situated at the top of the manara, and the mu’adhin to make his calls through a microphone at the foot of the manara. This is now the practice all over the Gulf and elsewhere, though it is notable that, in some parts of the world, the broadcasting of the adhan is not permitted for a number of reasons, the alternative being that it is called within the masjid.

Nowadays it can be argued that the manara is no longer necessary as loudspeakers can operate from a low position, and because most people are more aware of time than they used to be. However, there is a strong feeling in the Muslim world that the manara is an essential element of masjid design, as also they believe is the dome.

The qubba is often associated with a manara in the masjid grouping. A number of masajid have more than a single manara, an arrangement that must be designed for external viewing rather than the original, functional requirement of calling the faithful to prayer.

To the Western-trained designer, with the educational emphasis on forms and massing, the qubba and manara combined with the, usually, rectangular forms associated with the salah and its complementary accommodation, are an opportunity for sculptural inspection, for balance and counterpoint, for sciagraphic, colour and urban design studies. The masjid is an opportunity for external moulding and manipulation.

But the manara is now redundant from the point of view of its being created as a point from which the mu’adhin would call the adhan. It is even less of a requirement in countries where broadcasting is forbidden due to noise restrictions. My feeling is that there is a strong argument for it to be included where it is permitted to broadcast the adhan as it can be said that it is an excellent location for the loudspeakers which are used nowadays.

There may even be a case to make – where broadcasting is not allowed – for a manara to be incorporated as an urban design element in order to assist in the identification and location of the masjid. However, it is very much debatable how far masajid in the Gulf, particularly in Qatar with its wahhabi traditions, should be based on Western design principles. If form follows function, then the internal requirements of salah should obtain and be paramount. These do not call for ostentation, nor do they have a form that should be reflected in the external form of the development. If anything they should be reflect a privacy and a unity of purpose that typifies Muslims and their relationship with Islam.

Cloakroom

Earlier I mentioned the importance of cleanliness to a Muslim before prayer. One of the ways in which this is maintained is through the requirement for shoes to be left at the entrance to the masjid. In the Gulf it is common to see hundreds of shoes left outside the juma’a, usually flip-flops but, where shoes may be a little more valuable and where the weather may cause damage, it is customary to have a cloakroom immediately inside the masjid entrance where shoes can be left and coats and cloaks hung from pegs or folded on shelves. This is not a necessity for a masjid, but a practical suggestion.

Acoustics

The acoustics of the interior of masajid need to be good if the salat and khutbah are to be heard properly. There are three difficulties to consider:

- nowadays there is likely to be air-conditioning in most masajid. It is important that noise associated with the plant and air handling equipment is not intrusive;

- generally, the surface finishing of masajid is of hard materials such as plaster, marble and tiling though, usually, the floor is carpeted. These hard surfaces reflect sound and can create confusing acoustic conditions; in addition to which

- masajid tend to hold different numbers of people for the different prayers throughout the week, the absorbency this brings to the space has to be considered for the different numbers of people attending salat.

In addition to this, inductance loops may need to be considered for those with varying degrees of deafness.

Aesthetic requirements of mosque design

The functional elements are only one part of the brief for a masjid; the other requirement relates to its aesthetic elements.

The Prophet had a number of sayings attributed to him, including ‘God has inscribed beauty upon all things’, ‘God desires that if you do something you perfect it’, ‘Work is a form of worship’ and, particularly, ‘God is beautiful and he loves beauty’. In other words, that there is an imperative to produce works of beauty.

Consequently, it is held that the basic mandate for building design is to combine functional requirements with a sense of beauty. In the design of musajid this might be considered to represent the pinnacle of a design imperative.

What might be considered beautiful varies, of course, with every individual. There are regional differences which produce groupings of taste and introduce different vocabularies of design elements, but there is always the desire in Islam – particularly in the design of musajid – to produce a work of outstanding beauty. A coherent approach; one which appears to be the work of a single mind; a vocabulary which is contemplative in character and both supports and leads the user naturally to carry out the purpose of his visit; these would seem to be qualities capable of fulfilling the requirements of a design brief.

You will see that I have made no reference to function. Western trained designers hold function to be a generating force. ‘Form follows function’, is a famous saying that is held to be a truism. There are certainly functional requirements of a masjid; the cloakroom and ablutionary facilities which work effectively would be two simple examples. But a masjid should also follow Islamic architectural tradition in the Gulf, unless much of the architectural heritage is to be lost here too. While I have argued elsewhere that much has been lost of the residential character of traditional housing – and this to the detriment of those living in their new houses – I believe that there is a similar argument to be made for musajid as they move away from their integration with the community and borrow in an ecletic manner from the wide range of architectural styles available to the designer.

The common feature of architectural design which musajid share with traditional housing is the form and treatment of their internal spaces. Unlike most Western architectural design, Islamic design does not express the internal arrangements of its buildings in its external form. Thus the emphasis in architectural design is on the internal spaces of the building with the exterior often giving little away on what is happening inside.

Moreover decoration of the interior is intended to expand and extend space by disguising form, in a sense to create the illusion that space is unlimited, and that there is continuity. This, in the design of musajid, allows, or requires, the viewer to participate in the reading of the space, encouraged as he will be in this by the application of geometric, naturalistic and calligraphic patterning and by Quranic statement. This might sound like an intellectually challenging exercise to the Western mind, but it is no more than a result of being brought up in the knowledge and discipline of the Holy Quran. I should add here that the salah tends to have simplified decoration in order not to interfere with worship. The mihrab is usually the exception to this.

Perhaps I should have made the point earlier: the process of Muslims going to pray in a masjid has a significant amount of ritual to it. This is true if carried out elsewhere, of course, but the forms and procedures of the adhaan, the wudhuw’ and the salat – both fard and wajib, which are compulsory prayers, as well as for sunnah and nafl which, in the main, are optional – impose a significant series of duties on those going to pray, and require a contemplative, relaxing atmosphere to be induced in them if they are to be able to go through their prayers properly, bearing in mind that it is a sin not to carry them out honestly.

It seems contradictory that Islamic architecture is characterised by the manner in which the interior forms are not reflected in the external forms, and yet masajid tend to be thought of my most people, including many architects, as being typified by their minarets and domes. I would like to repeat here that this goes against the traditions of the Arabian peninsula, particularly the more austere wahhabi traditions.

Dome or qubba

The qubba, or dome, is a feature of many masajid, and is likely to have been derived from pre-Islamic sources in Persia. Strongly associated with the arch it was developed in order to span large spaces where trabeated construction would only permit relatively short spans. It also has the aesthetic advantage of introducing a very different spatial concept into interiors, as well as an environmental advantage in assisting with the control of warm air, the latter a feature of traditional houses with their tall ceilings.

The shape and tall volume produced by a qubba also tends to improve the acoustics of the salah, a characteristic which is held by some to one of the most important aspects of salah design.

These characteristics of the qubba combine to have the psychological effect of lifting the eyes if not the spirit, and might be thought similar to the effect ascribed to Gothic churches by the use of the arch.

Externally the qubba is a significant form in an urban landscape. Not only is the form a strong contrast to the generally rectangular constructions around it, but the form permits colour and decoration to give greater emphasis to its form. Gold and tilework tend typify the finishing materials of domes, making the qubba and the building it sits on stand out dramatically from the surrounding buildings.

Design decoration

Decoration is an intrinsic element of Islamic architecture, particularly of the design of masajid. Decoration in this context refers not just to planal decoration but also to the movement of planes to enliven and enrich essentially plane surfaces. I have previously referred to both the emphasis on the interior of Islamic buildings over their exterior, as well as the intent to extend spaces through disguising form, essentially through the use of decoration and modelling.

This manipulation of space is considered to be a creative process, yielding a result which honours both craftsman and those who come to pray. In its calligraphy it reminds the observer of his duties and responsibilities under the Holy Quran; in its use of shape it creates illusions and allusions which form and reform when reflected upon and, in its patterning – both naturalistic, calligraphic and geometric – it holds together in a governing, integrating geometry.

Changing views on mosque design

More has been written on the design of masaajid on one of the pages looking at Islamic urban design. Though most of the notes relating to the design of masaajid suggest that a burj or manara and qubba are necessary components of the design, this was not a requirement in the early days of Islam and, in some parts of the world, attitudes appear to be encouraging different ways of looking at the design of masaajid.

One of the ways in which attitudes are changing has to do with the perceived sensitivities of those living in countries that have only recently seen a surge in the numbers of Muslims living there. Australia is a case in point where the incorporation of a manara and qubba have been questioned in the design of a new mosque, an element of an Islamic Centre in Newport, Melbourne.

There is resistance to what many see to be the influx of Muslims in ’their‘ country, a visual reflection of this being the traditional features of masjid design – particularly the manara and, perhaps to a less extent, the qubba. In addition there are, in many urban developments, noise limitations that would apply not only to the calling of the faithful to prayer, but also the bells of Christian churches – so the traditional need for a tower to house a mu’adhin or loudspeaker is moot.

In the Australian example the qubba has been replaced by a ceiling of decorative but functional triangular skylights, and the manara by an extending concrete wall surmounted by a gold crescent. In addition to these features an attempt has been made to lessen what is seen to be the impenetrable façade and courtyard of the traditional masjid by opening it up visually both to passers-by as well as worshippers.

While the quality of the design is not affected by the lack of a manara, the internal flat ceiling, despite being enervated by the coloured skylights, does not have the spatial character of a dome, and it is easy to understand Hassan Fathy’s characterisation of the dome and its beneficial qualities to those inside. Removing both the qubba and manara has taken away the traditional image of the masjid and created a design arguably more suited to the present, a development that reflected the wishes of the clients of the Newport Islamic Centre.

Space and its deployment

Hassan Fathy, among others, has written about architecture being found in the continuity of spaces, their relationships, and the lesser importance of their containing elements. In the design of buildings and in the organisation of their spaces, designers spend considerable energy in resolving clients’ requirements in terms of the inter-relationships of functional areas. For the most part this is perceived by both client and designer as a two-dimensional exercise with clients striving to obtain the most for their money. But good architecture is so much more than that.

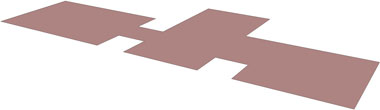

This first graphic represents a notional two-dimensional plan. It might be viewed as the type of arrangement a client and designer would come to agree as representing the functional relationships the client requires of his building.

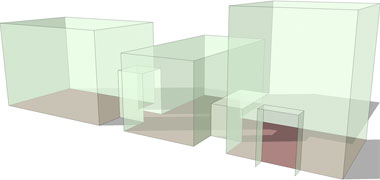

Here I have given the two-dimensional plan a perspective view. The sketch is not intended to illustrate a particular type of building but, in reality, most buildings would avoid the amount of articulation this plan exhibits in order to reduce both building and running costs due to the length of its external wall.

In developing a three-dimensional volume from the two-dimensional plan, you can see that there is considerable complexity that can be neither understood nor readily envisioned solely from the two-dimensional plan. This is the favourite way designers tend to investigate and create their buildings – as sculpture – and is also the common way of presenting buildings to clients as the building can be more readily comprehendable particularly, as here, when it there is a degree of transparency given to it.

This graphic is intended to illustrate a reverse internal view that I hope will make two points. Firstly, it demonstrates how little can be seen of the overall spaces, but how complex they may be and, secondly, a little reminder of how we really experience space – for the most part from floor level, in front of us and, generally, through movement in and around it.

The point of these four graphics is to remind how we are mostly based at floor level, and how space rises, usually above and around us. We understand the rooms of a building as two-dimensional elements but experience them as three-dimensional agglomerations. In experiencing them we also use them three-dimensionally rather than two-dimensionally and it is this which enables designers to bring spatial quality to buildings. Yet it is the two dimensional arrangements that concern most designers within buildings. It is an exceptional designer who is able to deal with three-dimensional internal spaces from the inception of the project, and it must be understood that many designers and clients find it easier to be swayed by the external appearance of a building.

Visibility and permeability

The concepts of visibility and permeability are important components of to our psychological and physical experience of buildings. They are also elements used by theoreticians investigating those qualities which help us understand how buildings are experienced and appreciated, and how they can be improved.

Visibility describes the extent to which we can see our way into and round buildings, how open they appear to us. It also describes how the building displays itself or, conversely, hides itself to us. Generally a degree of openness is sought by architects as it enables the user to obtain hints of where they may be going. This helps in way-finding and also in comprehending the two- and three-dimensional layout of a building. It also permits objects to be displayed, giving additional information to the spaces in which they are located.

Permeability, on the other hand, includes spatial qualities, but is governed by behavioural rules which establish how and who may have access.

The majlis of a building ranks high both for visibility and permeability as it advertises the owner’s presence by its visual openness and permits anybody to enter. This may be contrasted with middle-class Western homes where the interior of a house ranks high in visibility with trends to opening out the interiors by knocking rooms together, but which has a locked front door policy to improve security and retain internal privacy.

The spaces of a new residential building in the Gulf are not dissimilar in some ways from those that might be found in an, admittedly large, Western house. But as has been explained elsewhere, the relationships and the design work necessary to incorporate privacy requirements, bring about significant differences in the distribution of the functional spaces as well as their interrelationships. In a sense this is complicated by the rooms in modern Qatari houses being given names which Westerners use themselves, but with significant differences.

Let me take a specific example. These modern buildings have spaces which are not dissimilar from some of the classic buildings of the West. For instance, the importance of the entrance space and its relationship with regard to distribution into the majlis and dining room continues, but the difference in its relationship with a staircase access to the first floor of a Western building is theoretically not permissible as there is the need for the women of the house to move up the staircase – unless, of course, they have to use a different means of access to the first floor.

Despite this, many residential buildings use the hall as the starting point for a grand staircase up to the first floor level. The general solution to the problem created is for a secondary staircase to be provided within the family space. While this replicates the staircases provided for servants in classic Western buildings, this is not necessarily the solution for women of the house who have equal status with the men.

There is, however, a working solution, and that is for the majlis to be located somewhere else where there will be no conflict created by this privacy issue. This is the solution which is generally found. The majlis complex is created as a separate building and the house is designed with a majlis and dining room, entrance and grand staircase, this time to be safely used by all the family.

Permeability is low between the male and family areas of the residence of necessity, but both sides of the privacy line enjoy relatively high visibility, particularly with regard to the majlis complex.

Within the family side of the house there are similarities with Western houses in the interrelationships of functional spaces. The differences are difficult to explain but mainly relate to the number of people using Qatari houses and the fact that there are usually servants employed within them. My experience of the interiors is that doors of rooms used in the daytime are generally left open, and that bedrooms are left closed. Where children are using their bedrooms for studying there is often movement between them, boys and girls maintaining some degree of privacy. Women move around the house freely, both family and servants and, curiously, male servants who have a degree of freedom within the house. The numbers of women moving around can be quite large and generate significant movement and noise emphasised by the general dominance of hard surfaces, particularly in the kitchen. This is not meant to sound unpleasant, it’s actually rather lively.

A curious adjunct to this is that although furniture is distributed in the manner anticipated by the general designation and use of a room, the room may not be used as expected. More than this, it is not unusual to find areas such as corridors being used as a majlis by the women of the house. Visibility and permeability are rather different in reality in Qatari houses from the manner in which they may assume to be from the design intent.

As a general rule spaces within a building can be thought to have specific functions linked by circulation spaces which have the purpose of maintaining those functions and activities by insulation or isolation. Circulation spaces tend to be informal and, in having no defined purpose, act as spaces where more informal contact can be made. This is believed to facilitate social actions not as readily made in more formally designated spaces. As such they function as multi-purpose spaces allowing a variety of uses such as that of the majlis mentioned above. In particular, they are perceived to enable activities which are not permitted in structured spaces. They free or enable people in their daily activities.

This seems to be a benefit created by the geometry of designing large houses. It is not possible to expand a small house into a large house with more rooms in it without incorporating more ancillary spaces. In Qatari houses these circulation spaces can be relatively large and, in this, require dressing with furniture and furnishings, in effect creating more rooms but without specific designations.

It is important to remember that there are several groupings of people within a house, and that they will display or hide a wide variety of similarities and differences. This suggests there should be a variety of spaces to incorporate a range of informal activities. It should be considered that there will be distinctions to be provided for which will include but may not be limited to:

- cultural distinctions, between hosts and guests,

- power, between hosts and guests,

- gender, between men and women,

- generational, between adults and children,

- power, between householders and servants,

in addition to which there are many other aspects of living in a house which relate to aspects such as:

- time of day and night,

- season,

- religion,

- family celebrations,

and so on. The point being that many of the relationships can and are dealt with in the spaces with formal designations, but the intermediate or transmission spaces, permit a different kind of relationship – and there are more of these kinds of space within Qatari houses.

Islamic house design

While the notes on this site mostly refer to Qatar, it might be useful to set out something relating to the design of the traditional Islamic Arab house against which the traditional Qatari house can be compared. The following notes will look at the way in which traditional houses were designed, taking as examples mostly the architecture of Egypt, Iraq and Persia. This architecture is certainly different from that which was constructed in Qatar, but the principles are similar, combining as they do responses to the environment with the regional socio-cultural attitudes of Islam. Essentially the houses focussed on internal courtyards to be enjoyed by the family, with these parts of the house separated from those areas where male guests would be entertained.

The first group of differences are those of the construction materials and consequent construction techniques which vary, as you would expect, from area to area dependent upon the natural resources of the region. This means that features such as domes and vaults, which are usually constructed with bricks or blocks, were not used in traditional Qatari architecture. Nor were glazed tiles manufactured in Qatar, though both bricks and tiles were elements of the vocabulary of Persian architecture, albeit more likely used on buildings other than housing.

A second set of differences arises from the funds available for building. Generally the architecture of Qatar housed people with limited means at their disposal with which to construct extravagant houses. Quite the opposite, in fact; houses used available raw materials with considerable re-use of the wood needed in the construction of flat roofs and secure doors, and iron bars on windows. Thus the spaces created tended to be minimal, their spans dictated by the shandal supporting roofs, and the spaces accommodating a relatively high density of occupation.

From a Western perspective the form of the traditional Islamic house is difficult to see as, in its introverted form, it gives little of itself to the outside world, this resulting from the combination of its response to the Quranic requirement to eschew ostentation together with the need to create privacy for the family. Yet within the house, where the forms and internal spaces can be experienced, they were well considered and created a variety of volumes, each suited to its function – that function being a reflection of the behavioural needs of the inhabitants as well as of environmental engineering.

It is significant that the architecture of the northern Arab states has developed over centuries, if not millennia, whereas Qatari architecture can be traced back a relatively short time, much of it being related to defensive structures responding to the history of the peninsula. It follows that not only are the architectural forms and vocabulary less sophisticated than the northern states, but that they reflect the socio-cultural behaviours and needs of the Qataris, a society developing from both the merchants inhabiting the seaboard and the badu moving in from the hinterland. In both these circumstances the housing that was developed were typically a form of courtyard development.

Yet the courtyard is not an Islamic invention, its introduction to the region goes back to Graeco-Roman traditions in both rural and urban situations within the region, though its origins are even earlier in other parts of the world.

There are a number of benefits to this form of development, the enclosing walls of the traditional house not only creating privacy for its occupants but also focussing on the household and its own centre, the courtyard. These containing walls, enlivened by planting, are open to the sky, this element with its natural mobility through the day and night, reflecting the Arab view of the cosmos where the four walls of the courtyard represent the four columns supporting the dome of the sky, and where the walls define for the household their own private part of the sky, this first sketch illustrating the notional view of the house with its over-arching hemisphere of sky.

The enclosure framing that part of the sky which acts as a ceiling to the courtyard reinforces the feeling of privacy and introversion for the family – a more realistic view of this relationship can be seen in the photograph above heading this part of the note. The visual – and to some extent, aural – isolation created by the surrounding buildings helps to reinforce not only the cohesion of the family within their dwelling, but also their connection through religion to the natural world represented by the sky and the movements within it, day and night.

In the Arab world there is a distinction between the urban and rural forms. As I have illustrated elsewhere, the development of rural houses produced a relatively loose urban form comprising of rooms and a courtyard. It was only in the more restricted urban areas that the space available produced courtyard houses, often two storied, where the courtyard was completely surrounded by the rooms of the house. But rarely was this type of courtyard house developed as such, usually they grew as an agglomerating process, one that tends to create irregular courtyards – dissimilar from this illustration of a more regular courtyard – and one which abstracts courtyard space incrementally as the expense in the creation of rooms.

more to be written on...

regional architecture

provision for women zanana

lack of formal arrangement

and these to be fleshed out...

independent of material, scale and technique.

same ideas, forms and designs constantly occur.

illusion of different planes created through the use of colour in two-dimensional pattern.

reflective, shining materials.

continuity of patterns through floors, walls and ceilings.

contrasting textures.

manipulation of planes.

space is defined by surface.

surface articulated by design.

endless permutations.

structural and non-structural dissolving.

calligraphy important as it sets down the word of God.

proportions. geometry.

geometry, repetition, symmetry and reflection.

responsible for the underlying structure of the whole of the building and its furnishings.

arabesques establish spatial effects through varying width, splitting of the line, colour, texture. balance establishes lightness of touch.

related to geometry.

Waffle, waffle ...

Islamic / Arabic geometry 04 | top | Islamic urban design 01

Search the Islamic design study pages

- Introduction

- Arabic / Islamic design

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 01

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 02

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 03

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 04

- Islamic architecture

- Islamic urban design 01

- Islamic urban design 02

- Islamic urban design 03

- Islamic urban design 04

- Islamic urban design 05

- Arabic / Islamic gardens

- Gulf architecture 01

- Gulf architecture 02

- Gulf architecture 03

- Gulf architecture 04

- Gulf architecture 05

- Gulf architecture 06

- Gulf architecture 07

- Gulf architecture 08

- Infrastructure development

- The building industry

- Environmental control

- Perception

- The household on its lot

- A new approach – conceptual

- A new approach – principles

- A new approach – details

- Al Salata al jadida

- Public housing

- Expatriate housing study

- Apartment housing

- Pressures for change

- The State’s administration

- Society 01

- Society 02

- Society 03

- Society 04

- Society 05

- Society 06

- History of the peninsula

- Geography

- Planning 01

- Planning 02

- Population

- Traditional boats

- Boat types

- Old Qatar 01

- Old Qatar 02

- Security

- Protection

- Design brief

- Design elements

- Building regulations

- Glossary

- Glossary addendum

- References

- References addendum

- Links to other sites