a collection of notes on areas of personal interest

- Introduction

- Arabic / Islamic design

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 01

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 02

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 03

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 04

- Islamic architecture

- Islamic urban design 01

- Islamic urban design 02

- Islamic urban design 03

- Islamic urban design 04

- Islamic urban design 05

- Arabic / Islamic gardens

- Gulf architecture 01

- Gulf architecture 02

- Gulf architecture 03

- Gulf architecture 04

- Gulf architecture 05

- Gulf architecture 06

- Gulf architecture 07

- Gulf architecture 08

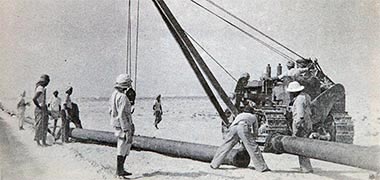

- Infrastructure development

- The building industry

- Environmental control

- Perception

- The household on its lot

- A new approach – conceptual

- A new approach – principles

- A new approach – details

- al-Salata al jadida

- Public housing

- Expatriate housing study

- Apartment housing

- Pressures for change

- The State’s administration

- Society 01

- Society 02

- Society 03

- Society 04

- Society 05

- Society 06

- History of the peninsula

- Geography

- Planning 01

- Planning 02

- Population

- Traditional boats

- Boat types

- Old Qatar 01

- Old Qatar 02

- Security

- Protection

- Design brief

- Design elements

- Building regulations

- Glossary

- Glossary addendum

- References

- References addendum

- Links to other sites

The old buildings of Qatar

These two pages illustrate something of the older buildings and associated development in Qatar. They might usefully be read in association with the page looking at the history of the peninsula. A number of the photographs on this page are taken from the web site of the Qatar Embassy in Washington and are placed here under what I believe to be fair use, permission having been requested. There are also photographs from the web site of the Diwan al-Amiri in Qatar. In addition to these I have also been kindly directed to photographs on here and, from there found a link to this site, though you will find a certain amount of repetition on all these sites. These four sites have many more photographs than I have used here and I recommend them to those with an interest in the country. The first two photographs here, are likely to have been taken from the same image, captured in April 1937, and show an aerial view of the ruined fort at Helwan, situated to the south-east of Zubara.

Also included are photographs taken from a publication of the Qatar History Committee in 1977. My intention here is to show as wide a selection of old photographs as I can find in order to present a rounded picture of the immediate past of Qatar by the addition of what I hope will be an appropriate commentary. These photographs are a relatively limited resource at present, but I’m sure that, with time, more will become available and, if relevant, posted here. More probably, the State will make a concerted effort to obtain and record images from the past as part of its Museums programme.

Having said that, throughout these notes there are many of my own photographs scanned from 35mm Kodachrome transparencies I took mainly in the 1970s and 1980s, though they are not all individually dated. While they are usually not as old as the black and white and sepia images, they are sufficiently distant in time to record something of Qatar prior to its most recent developments.

This colour photograph, for instance, was taken in March 1975 at al-Zubara and shows what I recall as being the only part of a building of any significance still standing. In the background can be seen the military fort with its westerly extension to the right, later taken down. Regrettably I have no knowledge about the building and what its use might have been.

This next photograph is also of ruins at Zubara and is said to have been taken in 1960. I am not sure if it is the same building as that shown in the colour photograph above but feel it might be as it was the only building of that height at the time I took the photograph in 1975, and there are certainly similarities in the detailing of the arch on the right. I have come across no other photographs of structures in that area of anything approaching this height. As to what purpose the building had, I am unsure, but there is a suggestion in the two photographs which follow it – and are of the same building, but six years later on, taken in 1966 – that it is the remains of the house of a pearl merchant.

Whatever its function, the outside of the building illustrates a relatively defensive attitude in the small apertures some distance from the ground, though there do appear to be semi-circular openings at ground level – either doors or, more probably, windows – and located within an arched wall construction as can be seen in the upper photograph which illustrates its interior. The walls and arches are of masonry construction and, unusually are dressed in order to provide a degree of accuracy and structural coherence not attainable with the regular hasa construction of most of the traditional buildings in the peninsula. Note that the wall appears to show springing suggesting that there might have been a domed construction, or at least arches – it was difficult to see from the original photograph if the springers were developed laterally to support domes. The final image in this group seems to have been taken at an earlier time than the two images immediately above it as it shows the two arches still standing and seems to be coaeval with the first of this group of four images and has been taken from a similar viewpoint as that immediately above it.

This aerial photograph is of the old development at Zubara. It is said to have been taken in the 1960s, but I have no other information that would give a more exact date. However, as we know that the two photographs immediately above were taken in 1966, this photograph must have been taken before then as it can be seen that there is more of the building standing in ruins at the lower centre of the photograph. A detail of it is shown below. The image is not of high quality as it was photographed directly from the original black and white aerial photograph.

Where possible I have put dates to the notes and photographs based on a number of considerations. Some of the photographs had dates associated with them, usually written on their backs, but I have discovered that they have not always been accurately ascribed. Because of this I have had to make assumptions. Please be aware of this in reading the notes. Should you have more accurate information I would be grateful if you would let me know so that I can correct or add information where appropriate.

Finally, I have found it difficult to make this and other pages logical essays; it will have to move backwards and forwards in time, location and type of building. My apologies for what follows…

Despite the foregoing, it is intended that these supporting notes will constitute a form of essay based solely on the photographs, hopefully tying them together in a manner that makes sense. There is a warning: I have corrected some previous mistakes I have made and I have corrected mistakes made by others, both in dating and in mirroring some photos as well as attributing incorrectly. It has been difficult dating some of the photographs and I may have made errors despite inspecting them as closely as possible. Because most images were small, this may have given rise to mistakes on my part. I hope not. I should also apologise for the uneven quality of the photographs. I have improved them where possible, but I have not attempted to create a similar look to each as, in doing so, I would have lost detail.

While the illustrations here are all photographs, there is some evidence from earlier days of how some of the urbanisations looked. In 1823 a ‘Trigonometric Plan of the Harbour of el-Biddah’ was published. It included not just a plan of the bay but also a sketch of the two towns of al-Bida and al-Doha. The sketch shows housing at al-Bida on each side of a square fort with circular corner towers situated near the sea. To its east there is a circular watch tower set back from the sea and, to its east, the housing of al-Doha around another square fort, this time having only two circular towers and one square tower. To its east there is another circular watch tower and, to the west of the fort there is a large building which appears to be a mosque. It may be significant that there are more boats pulled up on the foreshore at al-Doha than there are at al-Bida.

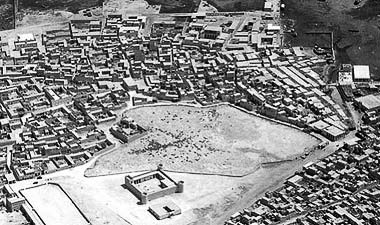

These first three aerial photographs – the first photograph above and these two below – are here because they are the earliest I have seen of any part of Qatar. The first of them is of a part of Zubara, the ancient development in the far north of the peninsula which was an important settlement for centuries, being the focus of interest for many of the families in this part of the Gulf. The photograph immediately below it was taken in 1960 and shows that there were some buildings still standing to first floor level. By the early 1970s these had all gone and there is little or nothing there now.

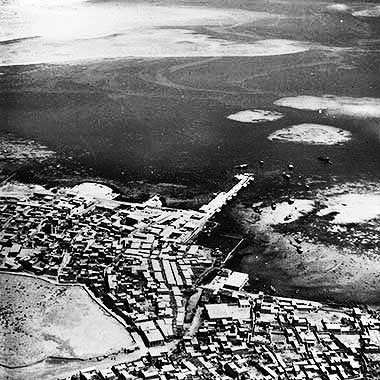

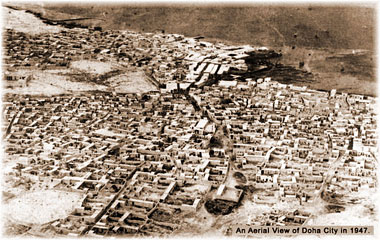

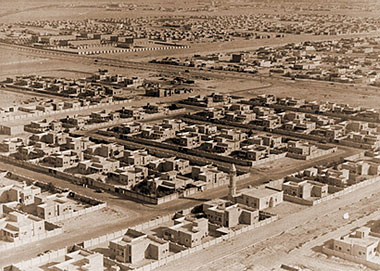

This aerial photograph is of Doha, taken from the south-west in 1937, and shows the settlement at that time to have been a relatively small urban development arranged round the wadi musheirib, leading to the sea and where boats were brought through the shallow waters to serve the town that had, by that time, become the most important settlement in the peninsula. Note how the development stretches east along the littoral to feriq al-Salata where Sheikh Abdulla’s original settlement had been made. The photograph clearly shows the three reefs off the old jetty and demonstrates that the jetty had not yet been constructed, the boats being pulled up close to or onto the land. The structure in the foreground is the old Turkish fort, known as the al-kuwt. The road to Rayyan leads out of the bottom towards the left hand corner of the photo and the wadi musheirib from the bottom right.

This first aerial photograph is likely to be one of the earliest photographs taken of urban settlement in Qatar. Its particular interest is that it shows the relationship between the two settlements of al-Bida and al-Doha sitting on the coastline. In the nineteenth and twentieth century the sea here was known as the Bay of Bida, suggesting the pre-eminence of the settlement at al-Bida. But by the time this photograph was taken it is obvious that Doha has become the larger urbanisation with development on the higher ground west of the wadi sail and, to a larger extent, on its east side, the wadi being the centre of what is now suq waqf, a common pattern for settlement development where roads follow the lines of water courses. Between al-Bida and al-Doha sits a fort approximately where the Diwan al-Amiri now stands. The likely reasons for there being more development to the east of the wadi sail than the west may be two-fold. Firstly it appears from the photograph that the coast is more suited to drawing up fishing and pearling craft than it is to the west and, secondly, that the Ruler of Qatar, Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim, had developed his compound on feriq al-Salata, to the east of this photograph, illustrations of which can be seen further down the page.

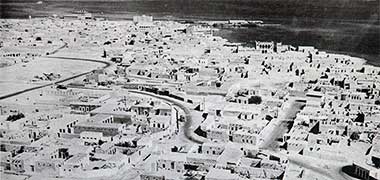

This second aerial photograph is taken from the same image as appears above, but was selected to concentrate on the development at al-Bida. Early images of al-Bida, made in the early years of the ninetieth century by a naval officer of the East India Company’s Bombay Marine, showed considerable fortifications to protect those living along this part of the coastline, and with al-Bida appearing to be more important than Doha. This characteristic was an inevitable consequence of development near the shores when the Gulf was awash with piracy based along its shores and on the Arabian Sea. However, by the middle of the twentieth century, this photograph having been taken post Second World War in 1947, the need for protection from attacks from either the sea or land had been diminished if not eliminated, though the building pattern would have reflected concerns pre-war.

The configuration of the urban development is interesting both for its spread along the littoral – reflecting the focus of the inhabitants of al-Bida in making their living from the sea – as well as for the apparent break in its centre, though I have no idea how this latter feature should have come about. Impossible to tell at this scale, it may be that there was a masjid located just north of its narrowest point. It is also noticeable that the buildings in the north half appear to be smaller than most of those nearer the fort. While there appear to be some transverse paths between the buildings to the shore, access along the development will have been mainly on the shore line. Note, too, the considerable extent of shallow waters in front of al-Bida, a feature which was still there in the 1970s and which was partly responsible for the decision to dredge the West Bay.

This next aerial photograph was said to have been taken in the late 1940s and from the south-east, showing more clearly the setting of Doha in its relationship with the West Bay. However, I believe it was taken on an aerial run in 1952 as close examination shows boats to be sitting or moored in similar positions to aerial photographs, taken in 1952, made from different angles.

The jetty at the end of the wadi Musheirib can be clearly seen with, at its northern end, the end extension that returned towards the east not yet constructed. More clearly, the three small reefs are identifiable as is the shallow land on the left of the photograph, east of al Markhiya, with the southern tip of jazeerat al Safliya just glimpsed in the top right hand corner of the photograph.

For comparison with both photographs, here is a photo of Doha taken in 1959. The photograph clearly illustrates how Doha and al-Bida were accessible by water, but with significant shallow waters to the west and reefs immediately opposite the centre of Doha’s suq.

The shallows were dredged in the nineteen seventies to create the New District of Doha, the reefs being used to form a base for extensions to the jetty developments as they were relatively hard and expensive to remove, as was another reef further out into the bay that was left and used as the base for the creation of an island that might form a focus within West Bay.

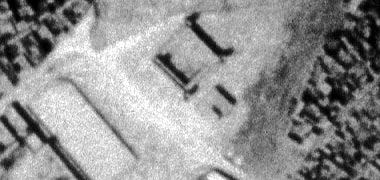

These two overhead aerial photographs of the centre of Doha may have been taken around the same time as the oblique above. The second is an enlargement of the centre of the first one. Close examination suggests they are similar. The road to Rayyan is evident, leading left and west; the road leading south may be the road leading to Wakra, though I believe there was also a track following the coast which would be out of picture, to the right. The site of the Diwan al-Amiri is clearly shown on the west side of the centre.

The next of this group of photos is a detail of that above. It is included in order to show more clearly the relationship between the suq, the maqbara, the al-kuwt and the open air prayer ground in the lower left corner of the photograph, as well as something of the texture of the residential and commercial development of Doha’s centre. It is a good illustration of a typical Arab town and its ad hoc expansion. Note that the maqbara is now the location of the car park associated with the redevelopment of suq waqf.

Here is another aerial view of centre of Doha, the photograph having been taken at a slightly different angle from that above. I am not sure of the date of the photograph, but the buildings look to be very similar, if not exactly the same as those above, suggesting that the photograph may have been taken at the same time, even on the same run. This photograph, particularly, illustrates how the littoral adjacent to the suq can be seen to be constrained – or protected by – the off-shore reefs.

Again this is a detail of the photograph above it and is placed here in order to get a better indication of the way in which the central suq was organised. The jetty which had been constructed against which the country craft could berth and unload their goods was a lineal construction. Some of the major merchants had their properties immediately to its west, or left in the photograph, and were able to bring goods straight into their warehouses adjacent to the shore. Near the shore the government had an area associated with Customs requirements, as well as a security facility.

Originally the suq was policed privately but, with time, this became a government responsibility. The suq can be seen to stretch back lineally from the jetty in two covered passages with interconnections, the wadi sail passing by to its east. Between the suq and the suq, the development was more haphazard and contained a mixture of residences, storage and some light manufacturing capability, the different trades being established as discrete areas. In this way there was a gold suq, and area of household appliances, another for staples and spices, one for tailors, and so on.

The next photograph of this group is marked as having been taken in 1952, and looks as if it might have been taken at the same time as some of those above it. The suq and fort are easily identified with the Diwan al-Amiri seen with a number of tarmaced roads associated with it as well as the road to Rayyan moving out of the photograph top left. The old development at al-Bida is also evident spreading along the shore line. This photograph may also be compared with the aerial photograph below.

Finally, a photograph, recently discovered, that again appears to be have been made on the same run as those above. Taken in 1952 it looks approximately south-west over the centre of Doha’s suq from a position a little way out over the West Bay. The maqbara sitting north of the Turkish fort – the al-kuwt – occupies a large and central area of Doha at that time, and it is possible to identify the new commercial developments to their south, their limits bounded by what would become Abdullah bin Thani street, on their west, and Musheirib street on their south.

While not overtly a demonstration of the old architecture of the peninsula, I have included this photograph as it gives an indication life in Doha in the early nineteen-foties. It shows a camel being loaded at the port, presumably the area immediately north of the suq, now referred to as suq waqf. To the left of the photograph is the end of a temporary building that appears to be a barasti construction with a pitched roof.

The photographs above illustrate something of the character of Doha which lived on until the early nineteen-seventies when the whole of residential accommodation in the central area began to be demolished. To give an even better indication of the texture of traditional housing, here is an earlier photograph of the feriq al-Sharq area of Doha, which was situated on a promontory north of the old development of Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim, north of feriq al-Salata, a small peninsula subsequently incorporated into the port area. Note here the pattern of reefs protecting and constraining the use of the littoral, and the fish trap to the west of the end of the peninsula. The present area known as al-Sharq is around a kilometre south-east of the area shown here, across Doha’s east bay. I can’t be certain of the date of either of these two photographs, but the top one is the older. I had thought that the lower photograph was taken in the early 1950s, but believe the image from which it is taken is similar to one I have seen dating from the late 1940s. Its significance is that, compared with the upper photograph, the area has been abandoned and the buildings are falling into disrepair.

Here is a view of Doha taken in 1952 and shows the urban development with feriq al-Salata in the foreground. The al-Sharq development can be made out in the bottom right hand corner of the photograph and Sheikh Abdullah’s complex would be out of picture on the left. The sprawl of Doha can be seen at the top of the photograph with the jetty stretching out from the end of the suq development. Behind it is the development of Sheikh Jassim with its associated jetty just visible and the road leading to Rayyan moving out of the picture and top right. The road on the left leads to Wakrah. Beyond Sheikh Jassim’s development is the settlement at al-Bida. Note the shallow waters edging the littoral, and how development tends to cling to the shoreline.

Although it is difficult to spot in this photograph, the small horizontal white shape slightly above and left of the centre is the al-Qubib masjid, of which there are photographs below.

This photograph must have been taken around the same time as those above and is looking around south-west across al-Sharq and feriq al-Salata. In this photograph the masjid in the foreground is the dominating feature of the urban development. It is a simple building, very much in the wahhabi tradition that produced architecture which lacked ostentation but created beauty through simple lines and proportions. The building can be seen in both the oblique and plan photographs above it. It is interesting to see how close to the water’s edge the masjid has been built, as well as to observe the simple nature of the housing.

Doha was overflown again in 1952, this aerial photograph having been taken from approximately the north-east. While the detail is not easy to see there are some features that are identifiable, even at this scale. The open space in the centre of the photograph is the central maqbara with, to its left, the al-kuwt, or Turkish fort. The new palace of the Ruler can be seen standing by itself just above mid-centre and, running along the coastline to its right, is the old town of al-Bida. Where the coastline runs out of picture on the right can be seen the masjid al-Qabib. The old suq al-Waqf can be seen between the sea and the maqbara. Out of picture, below the aircraft would have been the old palace of Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim at feriq al-Salata. It can be understood that Doha was, at that time, at least three separate conurbations spread along the sea edge – al-Bida, Doha and al-Salata.

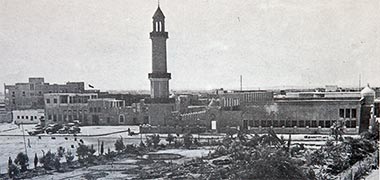

This photograph illustrates something of the character of housing in the middle of the twentieth century, the buildings being predominantly single storey with the the occasional first floor added as well as the manaaraat of masaajid visible. One of these is extremely obvious in the centre of the photograph and suggests it belonged to one of the new masaajid being introduced to the country, though there is a small manara, partly hidden, near the right hand side of the photograph. I believe the viewpoint may be looking approximately west or north-west over a part of feriq al-Salata, but am not sure.

This character of low building development with manaaraat rising above them was characteristic of Islamic developments over a wide region, not just of the Arabian peninsula but also of Iran and the areas immediately to the north, east and north of the eastern end of the Mediterranean. To illustrate this low scale of development compare the photograph of the derelict part of Doha above with the colour photograph below it that was taken in Isfahan in 1975. Note, too, that it is not manaaraat that rise above the rooftops of Isfahan, but qubaab and trees.

The photograph originally here was another found one, attributed to the Ministry of Information but having no date associated with it. This photograph is a better version of it. On inspection it seems to have many similarities with the photograph above, which was taken in 1952, and I suspect this may have been taken on the same run. Having written that, I have found a copy of it dated on the back at 1947. The reason it is placed here is that it has a rough quality to it which seems to accord with the character of the architecture of that time. It also clearly illustrates two of the main sikkak leading to the main suq and port at that time. The wadi musheirib runs horizontally towards the top left of the photograph, the Turkish al-kuwt fort just above it and adjacent to the maqbara.

This aerial photograph was taken, I believe, also in 1952 and may have been made on the same run as that above. Again, it shows the grain of the urban structure of Doha at that time, particularly the wadi musheirib and its relationship with the bay. What is particularly noticeable is that the foreshore is protected by a sand bar which, while allowing small craft to be drawn up, also constrained use of that part of the shore for commercial or other development. On the top centre edge of the photograph can be seen two, and a part of a third, outcrops of a hard material which, for a time constrained development in being too hard to remove. In fact the new wharf for the fishing and trading craft was incorporated over them.

This photograph is of a similar area of Doha, but shows more detail and was taken from a steeper aerial perspective looking approximately north-west. In fact, I suspect it was taken from the same image. I don’t know the date of the photograph as I took it from a document a long time ago, but I believe it dates from the late 1940s. Again, wadi musheirib runs across the top left of the photograph with the east corner of the main maqbara just visible. A number of sikkak can be seen leading north towards the suq with one of them apparently wider than the others. There are two interesting points to make: firstly, there is only one masjid in sight, just right of centre – though there is one just out of picture at the top of the photograph – and, secondly, there are no burj al-hawwa to be seen.

Here is another oblique image of that area of central Doha, feriq al-Jufairi, and was again taken in the 1940s. Captured from a more shallow vertical angle, but from a similar direction, it is relatively easy to compare the two images. The triangular open space towards the bottom right edge of the photograph above can be identified with that towards the centre near the top of this photograph; and a part of the central maqbara can just be glimpsed at the left of the top edge of the photograph. As might be anticipated, it is clear that the housing plots are generally larger as they move away from the centre of the suq with most of them lying adjacent to the wadi which annually took water to the bay to the north. Flooding in the suq due to this was an issue until the early 1980s.

This image shows the centre of the suq in a little more detail, looking from the east. The wadi leading to the sea is clearly seen with the main shopping area to the far side, west, of it. In the left bottom corner is the masjid. The wadi is now the paved road through the centre of suq waqf, and the masjid remains in the location shown. The suq extends north approximately as far as the old police station of the nineteen sixties, and boats have access right into the suq, the masjid being around 330 metres from the present shore line.

This aerial photograph was taken in 1954 and is said to show a part of the outskirts of Doha at that time. Inspection of the photograph suggests that it was taken looking more or less south, though I have not been able to work out exactly which part of Doha it shows. There is the beginning of a road leading out of the photograph top left, and a maqbara is cut by the bottom edge at its centre. The housing plots are generally orthogonal and laid out in the same direction – with one large, single exception near the top centre – and the spaces between the boundary walls are relatively narrow suggesting they were established in the nineteen-fifties. All the buildings are attached to boundary walls which also suggests the same time period.

Urban grain is always interesting as a guide to the character of an Arab town. This photograph is a detail taken from one of the oblique aerial runs made to record parts of Qatar in 1952, and looks approximately north-west with the sea near the top edge of the photograph. The larger image can be seen above. It shows the area immediately to the west of Doha’s central suq, now known as suq Waqf. The buildings are a mixture of one- and two-storey constructions with the ground floor ceiling heights relatively tall. These were the properties lived in by many of the merchants operating in the suq. Because of this the houses were also used for storage of goods and there would have been considerable movement of materials around the sikkaat with, for the heavier goods, the use of porters and their carts. Interestingly there seems to be no rule governing the orientation of the first floor constructions as there was at Wakra. While the sea lies to the east of Wakra with the first floor rooms generally facing it, the sea lies to the north of the centre of Doha. In addition activities in Doha were more oriented to commerce, Wakra to fishing and pearling. It is also notable that there seems to be little or no trees in this part of the centre.

Fortified structures

The Ottoman Empire established a fort in 1880, known as al-kuwt, on the rising ground west of the centre of Doha in order to control this strategically important port on the east coast of the peninsula. I am uncertain if the Turks constructed the building or if they occupied an existing structure, but believe the former to be the more likely. A small force was garrisoned in the al-kuwt, but left with the signing of the protection agreement of 1916 between Great Britain and Qatar. Subsequently al-kuwt was used as a prison for a time, this first photograph of it, being said to have been taken in 1945 or the early 1950s, depending on which source you look at.

The second photograph, taken from approximately the south-east, is not of great quality, but is included as it shows the internal form of the structure and its single, small, entrance. A detail of a photograph taken in 1952 it illustrates how the accommodation is built into the walls of the fort, providing a fire step above it. The line to the right, outside the fort, is the wall surrounding the central maqbara, now the site of the parking area adjacent to suq waqf.

This aerial photograph, taken from almost due south, and of better quality than that above, makes an important point about the internal layout of the al-kuwt fort. There is an open musalla, its mihrab pointing towards Mecca on the left or west. The main entrance to the fort was in the east, right, wall and was changed to the west wall at a later date but returned to its original, or almost original place, later. Entrances were made to the higher level of the corner towers from the fire step, with continual access through the rectangular tower along the fire step.

One point of note is that the main accommodation has been made in its south-east corner adjacent to the main entrance, presumably for military reasons. Traditional development of compounds in the peninsula favoured the north and west for environmental reasons and it appears that there is accommodation for the troops around the perimeter of the compound, forming the fire step.

There is a small entrance on the east wall facing the suq and maqbara which would make more sense as it would have been that more easily defendable. The accommodation to its south would support this. The maqbara had a wall around it for some time but it is likely that the area around al-kuwt would have been kept clear to keep firing lines clear. Having said that, an earlier photograph shows a building close to al-kuwt on its south side. I don’t know who built it, nor its purpose. In this lower photograph the ’eid masjid is on the left.

In March 1972, this is how the fort appeared, the photograph taken looking approximately south along its western wall. Across the road was what was referred to as the ’eid mosque and, at the end of the road, bottom right, the Arab Bank roundabout. This is how the al-kuwt fort appeared in its original form – the following years seeing a number of changes and interventions being made in order to provide housing for a museum and exhibitions, and then being returned to something similar to its original form, but with significant differences. More about its recent history can be read on another page.

While al-kuwt had its origins in the need to defend the commercial centre of Doha and was later used as a prison, it also became the location for some of the armed guards who patrolled the suq at night, a service paid for by the merchants who operated there. Here two of them pose to be photographed in June 1972. I understand that there were also less formally dressed guards living above the shops in the suq, perhaps a less expensive option for the merchants as they might also be employed in the shops by day. I may be wrong, but their dress suggests that at least the guard on the left is not a badawi, though that on the right may be, guards traditionally being found from among the badu.

The kuwt was constructed on rising ground south of the suq. The form is similar to desert developments in that a surrounding wall gave protection to an arrangement of rooms inside it. Inset in the walls and defensive towers there are fat’ha al murakaba, small holes in the walls which allow protected viewing and some ability to use small arms against attackers. You can also see on the photograph a number of mirzam designed to throw rain water away from the building, in this case also allowing some of the function of the fat’ha al murakaba.

However, although I have located this first photograph here in the context of Doha as it is officially labelled as being the al-kuwt, I am certain the photograph actually shows the fort at Zubara as there are significant differences between the two buildings. Compare it with the photograph above of the al-kuwt in Doha and, particularly, with the two photographs below it, the first of which is taken from a similar angle, from the south, though from a greater distance. The lowest of these photographs shows the Zubara fort from the north-east. The white marks in the centre photograph are likely to be patching to cracks in the walls, suggesting that the photograph was taken in the nineteen-fifties. The Zubara fort was constructed around 1938 in response to concerns for deteriorating relations between Qatar and Bahrain. It was used both as an outpost as well as a prison. Neither of these photographs are to be confused with the fort that was constructed immediately outside the town of Zubara, known as Murair, a fort constructed by the ’Utub in the eighteenth century, designed to protect the town from sea-borne invasion, and now ruined.

As mentioned in the previous paragraph, the north-west of Qatar held a particularly strategic importance in the history of Qatar and Bahrein right into the latter part of the twentieth century. Because of this there were a number of alterations made to the fort at Zubara reflecting the requirements of garrisoning the structure. Its architectural profile altered a number of times as well as its plan form. This image, taken in the 1960s, together with that immediately below show the fort with its extension to the south-east, later taken down and the structure returned to its original plan form as can be seen today.

The above photographs can be compared with this one, taken in March 1972, and looking at the fort from the south-east. At that time it was being used by the police or military and had been extended to around twice its original size in order to contain a more useful garrison in what was considered to be at that time, a politically sensitive area of the peninsula. The evidence of modern aerial photographs is that this extension no longer exists and that the fort has been reduced to its original form and functions as a museum.

As you can see, the two fortified structures above are relatively small and would not have been able to house, protect and sustain a sizeable military garrison and their associated administrative personnel. Here, however, are photographs of two larger fortified developments.

This is a rare photograph of the fortified development at al-Wakra. Constructed by Sheikh Abdulrahman bin Jassim al-Thani over a hundred years ago, the photograph shows the development on the left with, on the right, the four bays of the iwaan of Sheikh Abdulrahman’s masjid. The photograph was taken looking from the east and shows the development in considerable ruin. I don’t know the date of the photograph. Sheikh Abdulrahman was appointed by his father, Sheikh Jassim bin Muhammad al-Thani, to represent the town in 1898.

When I originally posted this old photograph, I noted that it had been taken in the nineteen-fifties and believed it to be the fortified development at al-Wajbah, west of al-Rayyan. However, it has been pointed out to me that it is not that fort, but the old Diwan al-Amiri complex just north of the centre of Doha. Regrettably, it means that I have no old photographs of the development at al-Wajbah other than those I took there in 1981.

This photograph is thought to have been taken around 1952 and shows the Diwan al-Amiri from, approximately, the south-east with the old Sheikhs’ masjid in the bottom left foreground. If the salient features of the building in this photograph are compared with those above it is evident that they illustrate the same building complex. The photograph above would have been taken from, approximately, the north-east, down by the old shoreline showing the majlis facing out over the bay. Entrance into the complex was from the east and south.

The above examples of fortified structures are mainly distinguished by a surrounding wall within which there are separate or attached buildings to house the personnel living within the forts. The surrounding wall has corner towers both to strengthen that part of the wall as well as to enable observation and enfilading fire if necessary.

But there were other types of fortified buildings in the peninsula and that at Umm Salal Muhammad north-west of Doha is a significant example. This first photograph of the structure was taken some time in the 1950s from approximately the west, the second in 1956, approximately from the south.

Said to be founded in 1910 by Sheikh Muhammad bin Jassim al-Thani, Umm Salal Muhammad is a small settlement in the centre of the country and is different from most of the other urban developments in Qatar for that reason. Its climate is drier than the conurbations on the littoral, and it has a gardened area of date palms with ground crops beneath them supported by a reservoir of water contained by a small dam. In the 1970s there was little water to be seen in the reservoir, the rumour being that drilling into the reservoir had created the means for water to escape.

To the south and west of this resource a coalescence of residential development grew up as can be seen in the photographs, the development including a masjid to the north of the structure and west of the reservoir. However, compared with Doha and Wakra to its south, Umm Salal Muhammad was relatively poor and, to some extent, this demonstrates one of the differences between the badu, interior settlements, and the trading and fishing settlements on the coastline.

This photograph was taken in March, 1975 and shows the elevation of the residential structure facing south-east with its tall semi-circular headed arched iwan apparently at odds with the detailing of the heavily fortified walls. The construction of the columns can be seen to be heavier than might have been expected in a residential building, such as would have been seen in Doha; nor were there timbers between the columns to provide additional support, as was a feature of many residential constructions. While apparently abandoned, there was evidence of people living in and around the courtyard at that time.

As mentioned above, the development at Umm Salal Muhammad was constructed by Sheikh Muhammad bin Jassim bin Muhammad al-Thani prior to the First World War and there is an obvious connection to the architecture of the Nejd. I believe that Sheikh Muhammad was also responsible for the structures now termed the Barzan towers, in 1910, and to the east of Umm Salal Muhammad, this view of one of them being from one of the defensive openings in its walls, facilitating easy communication between them. This was to be his winter quarters from which Umm Salal Muhammad could be overlooked as well as any intrusion moving south into the peninsula.

In the flat landscape of this part of the peninsula the development contains a tall tower which permitted anybody in it to see some distance and give warning in the event of attack. In addition to the residential development there is also a pair of towers to the east of the town which, I believe, were constructed purely for this purpose. This view of it, taken in February 1976, shows the view of it from the gardens to its west.

Strictly speaking the next images are not fortified structures but have been included to show a little more of the setting of the main fortified structure within Umm Salal Muhammad which was an extremely attractive piece of urban landscaping.

The next two aerial photographs are instructive in that they demonstrate what is happening with some old structures in the peninsula. The first is an aerial photograph of the fortified house in its setting in July 2011. The gardens to its west are clearly seen as is the masjid to its north. The residence to its south within its containing wall is also evident and was inhabited in the 1970s and, I think, 1980s. To the west of the structure and across the road was the dammed wadi which filled in winter.

It is also significant that there were changes to the grouping prior to the area being recorded from the air. In the 1970s the masjid had a different form with there being an open courtyard flanked by a burj on the south-east corner compared with it being on the north-east corner as shown above. In addition, to its north and just out of picture here, there was a building with porch facing south and, to its east, a small square open prayer area. This photograph shows the masjid from the east in March 1982. A little more of this masjid can be seen in two images on one of the Gulf architecture pages.

Taken in November 1977 looking towards the position from which the above photograph was taken, this photograph shows the old building which backed onto the planted area to the north of the grouping, and faced the north wall of the old masjid. To its right, and painted white, was a raised square area which at first I assumed was an open prayer area but, on reflection, was more likely to have been a open area established as a majlis or baraha.

Here, however, is the aerial view of it taken two years later, in July 2013. Everything around it appears to have been demolished. The house and its compound, the masjid and gardens have disappeared and something seems to be happening to the dammed wadi. I have no idea what plans there are for it but my recollection of the whole grouping is that it was one of the most attractive natural groupings in the peninsula. Admittedly the single storey housing was sub-standard, the strongly articulated ground modelling combined with the trees of the gardens made this a lovely place to visit.

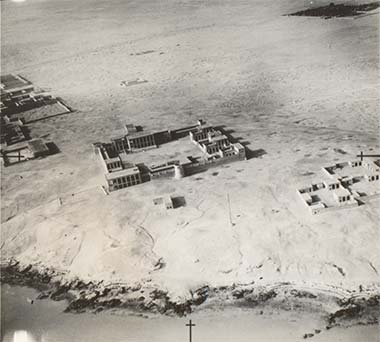

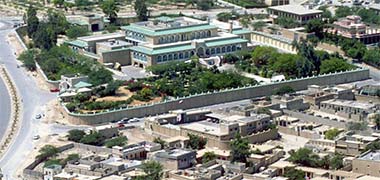

Finally, here is a more modern structure, but one which replicates the pattern of the traditional forts of the peninsula, albeit on a much larger scale. This oblique aerial photograph was taken around 1968 and shows the fort at Rumaillah, looking approximately north-east. Housing both Police and Army headquarters, the fort, around 250 metres square, was constructed on the high ground, north-west of al-Bida and around 600 metres from the sea, which can be seen in the background. The line of the shore there changed with the development of the New District of Doha and the associated Corniche.

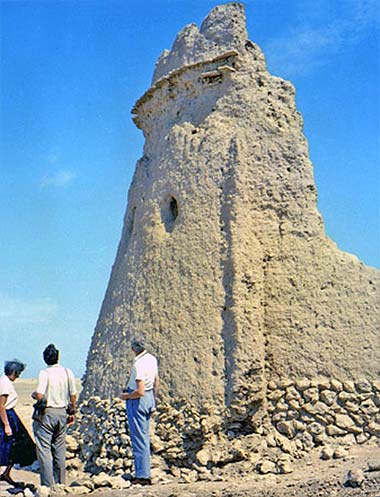

This photograph was discovered on an official government site. Many of its photographs can be found elsewhere, but this is the only image of this particular structure I can find. Regrettably there is no accompanying description so I am unable to locate it. From the style of dress I would guess the photograph was taken in the 1960s.

It is not clear to me from the photograph how the tower was constructed. Originally I had thought it was not of hasa but of mud bricks, but have been informed that it is of masonry construction. I wonder if there was a form of construction which utilised mud but added small stones as aggregate. Certainly the upper construction appears to be radically different from its base.

I also believe that this is likely to be a corner tower for an protected space contained by a wall. A trace of the wall can be seen, thick at the base and narrowing to the top. Like the corner burj the wall is founded on around a metre height of hasa for stability and strength. There are fat’ha al murakaba in the walls and the top of the burj has been articulated with shurfa, both designed to protect those defending the development. There is still the possibility that this might be a free-standing tower, and that a structure has been added to it at a later date.

It is unclear why defensive structures of this sort should be built of mud rather than hasa, but there may be a number of explanations. From a structural point of view there may be few hasa in the immediate area, but enough quantities of soil to use in a teen construction. A secondary reason may have to do with the time required to construct a stone or teen structure. This would reflect the urgency with which the building was required. One peculiarity about the burj is the location of the fat’ha al murakaba with respect to the walls. A better location would have the fat’ha al murakaba nearer to the wall in order to permit enfilading fire from the defenders along the wall.

The White Fort at Anaiza

This next group of photographs relate to an old fortified residential complex just to the north of Doha, an area now completely covered by the development of the New District of Doha. My attention was drawn to it through attempting to discover more about an oblique aerial photograph, taken in May 1975, of a small complex of buildings adjacent to the coast in what turned out to be – with the assistance of staff of the Origins of Doha project – the area now covered by the New District of Doha. The first of these two illustrations shows the location of the building, the second shows the area and its relationship with the New District of Doha in 2017. The area marked in sepia on both illustrations is the site on which radio aerials were erected, I believe in the early 1940s, around which a wire security fence was constructed. The area was known as Anaiza though it appears now to be referred to as Unaiza or Onaiza.

This animation is intended to show two aspects of old development in this part of Qatar. Firstly, the location of the building photographed in 1975 that led me to learning a little more about the development at Anaiza – this is located by the red dot; and, secondly, the location of the whole of the Anaiza development which is shown superimposed on the radio aerials site and was known as the White fort. What is important about the map is that it shows the south-east corner of the security fence as a re-entrant in order, for reasons yet to be determined, apparently to avoid conflict with the building.

I’m told that the White fort was a feature of Persian Gulf marine charts, acting as an aid to navigation until the late 1940s. Presumably its towers would have been of a similar height to those at Doha and al-Bida.

This photograph was taken or developed in May 1975 and is interesting for a number of reasons. It took some time to locate where it was taken, and that was only with the assistance of staff at the Origins of Doha project. The photograph was taken from approximately the south-east and shows the development in ruins with, at the top of the photograph, the corners of the re-entrant security fence of the radio aerials site. The development sits in an area where there is considerable sabkha, and the bottom right corner of the photograph shows its proximity to the shore line. When working the area just to the north of the radio aerials, the government’s Engineering Services Department had considerable difficulties caused by working on the sabkha.

The larger photograph is a detail of the first. Regrettably this is the only photograph I have of the building and it is difficult to make out the details of its construction. However, the building appears to have been constructed of concrete blocks raised on a buttressed base of desert stones. Its single entrance faces due east and its roof is flat, apparently constructed in the traditional manner with danjal mangrove poles and at least one mirzam to move rainwater off the roof – though I believe this would be insufficient. I have no idea what the central, reddish, structure was. It appears to be different in character from both the building as well as its surrounding structure, the only similarity being that it is the same height as the room, and possibly connected to it.

But it is the surrounding construction that is difficult to understand. It appears to consist of a series of square desert stone columns sitting on a wider base, with infill panels, apparently of desert stones, that have collapsed. On the east side there is a solid feature whose purpose I can’t guess at and, on the north side, apparently an entrance. As for the two corners on the east side, they appear to be solid circular constructions resembling traditional circular corners structures of fortified buildings, but on a much smaller scale.

There is evidence that this small building was connected to the larger development at Anaiza on its south-west side or corner, and this seems to be borne out by the oblique aerial photograph as well as by the overhead aerial photograph. In this illustration, the White fort, as the larger complex was known, has been superimposed on the 1971 plan of this part of north Doha, with the small building circled in red.

The development at Anaiza was the residence of Sheikh Khalifa bin Qassim al-Thani, the second of the nineteen sons of Sheikh Qassim bin Muhammad al-Thani. Sheikh Khalifa was born in 1851, and died in 1931, which may suggest dates for the occupation of this development and for its abandoning.

The al-Thani family scattered their residences around the peninsula both inland and, as here, on the littoral. Sheikh Khalifa’s younger brothers, Sheikh Abdulaziz, Sheikh Muhammad and Sheikh Ali were the shyuwkh respectively of nearby al-Gharafa, Umm Salal Muhammad and Umm Salal Ali with Sheikh Fahad the Sheikh of al-Khisah, Lusail and Rumaillah. Another younger brother, Sheikh Abdullah, the Sheikh of al-Rayyan, became the Ruler of Qatar with his development on the littoral at feriq al-Salata being made into the first National museum.

Right into the beginning of the twentieth century there were political issues that saw a concern for conflict on the peninsula. Because of this most, if not all of these residential developments, had elements of a defensive character. Usually this was confined to a relatively small area of the development and consisted of a high containing wall with round and square turrets at the corners. In the case of Anaiza it is difficult to work out exactly how the development was guarded.

Here is the only image I have seen of the White fort at Anaiza, a photograph taken by the Royal Air Force and reduced for the purpose of superimposing it on the plan above.

The fortification appears to be confined to the south of the development with a circular tower in the south-east corner and, perhaps, one on the south-west. There is evidence of structural planning to accommodate family and retainers of the Sheikh. The family’s residential accommodation appears to take up the northern part of the development while in the southern part, to the west of the fortified south-east corner, there appears to be smaller repetitive courtyard housing, perhaps for guards or retainers. The south-east corner of the development, with its rhomboid shape, looks as if it was designed as a fort, but there is rarely building attached in the manner in which it is to its west, as this would weaken its purpose. However, the possible tower on the south-west corner would suggest an attempt to extend the fort defences, incorporating the residential element.

The manner in which the development was laid out shows a continuous wall around the north, west and south sides, but is broken on the east adjacent to the sea where there is a masjid, an important element of this type of housing, its position enabling all to visit regardless of status. It is probable that shallow draft traditional boats were pulled up onto the shore at this point in a similar way that was witnessed at feriq al-Salata.

It is evident that the Government will have purchased the land in order to construct the radio aerials, and this land would previously have been in the ownership of Sheikh Khalifa and his family. The exchange would most probably have taken place some time after 1931 when Sheikh Khalifa died and assuming the family moved to better accommodation elsewhere. The buildings would have been allowed to collapse naturally, though it is possible that some of the elements of their construction were stripped out and removed to use on new constructions.

As for the curious building addition which began this search for evidence, it is still impossible to state its purpose. The evidence of the RAF photograph is that it was constructed after the rest of the fort was abandoned or, if it was added when the fort was occupied, then it is likely to have had a different function. Previously I have noted that it seems to be of concrete block construction and would, therefore, have been a later addition and less likely to deteriorate – though this would not necessarily apply to the roof construction.

The building seems to me to be

- too small to have been a majlis – and there appears to be no evidence of an external baraha arrangement that I would have anticipated,

- too early to have been constructed for soldiers guarding the radio aerials – though it may have later had this function either for the border police, coastguards or for Cable & Wireless guards,

- too weak structurally for a defensive element,

- not tall enough to have been a defensive tower, and

- uncharacteristic and too complex to have been a sally-port.

If anybody has more knowledge or a suggestion, please let me know…

Development in Doha

This is the oldest aerial photograph I have come across showing Doha. Taken in May 1935 from a British Royal Air Force flight and looking approximately south, it establishes the character and extent of Doha at that time with the town expanding to the east and south. The photograph illustrates the consolidated shoreline just right of centre, where leading merchants developed the littoral in order to create areas for the goods they imported to be landed and stored. The set-back, left of centre is the original harbour where the wadi Musheirib met the West Bay and behind which suq Waqf was and is situated. I’m not sure, but it is possible that the dark area situated some way south of Doha is al-Nuaija.

The Turkish fort, al-Kuwt, is clearly seen sitting behind Doha’s central maqbara and, although it can not be seen at this scale, the al-Qubib masjid is near the foreshore on the left of the main photograph above. The area of shallow water is evident on the left and the three reefs a little way offshore are clearly seen, later forming part of the structure of the first proper harbour.

Note that the masjid in the centre of the suq is situated to the west – right – of the wadi, whereas it is now situated on the east of the wadi, now the main road through the suq, though I don’t know exactly when the development of the road will have established this.

The area of old Doha in the centre and adjacent to the sea, is the area of feriq al-Jasrah, now some distant from the sea due to the creation of two roads running east-west, first that trimming the edge of the sea and, later, the installation of the Corniche. These two photographs were taken in 1945 from buildings fronting onto the west bay of Doha in feriq al-Jasrah. The first looks approximately north-west, the second approximately south-east. Behind the buildings in the first photograph, the rise on which the Diwan al-Amiri was constructed can be glimpsed with the littoral of the west bay moving north to the right of the photograph. In front of the buildings in both photographs can be seen the unpaved foreshore with, in the lower photograph, a rowing boat drawn up. Small craft enabled the larger boats to be unloaded and their goods brought straight ashore to the houses of the merchants living by the sea. I believe that the building in the lower photograph belonged to the al-Mana family. Behind the lower buildings can be seen the masts of abwam in the main harbour of that time.

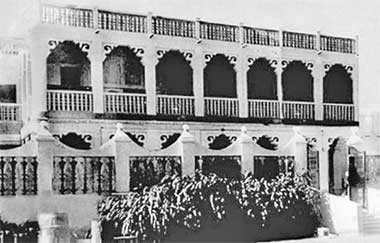

This photograph was taken in the 1950s and shows a building which is said to have housed British residents, perhaps associated with the British political presence of the time. The building shows the influence of Bahraini architecture in its simple trabeated form. The open nature of the façade and front wall shows it would not have been lived in by a Qatari family. The decorative treatment in the angle between columns and beams is simple but refined, enlivening the rigid orthogonal architecture of the building.

al-Jasra street was the name of the road that was constructed to the north of, and along the frontage of Doha’s centre, crossing the central suq and extending to the Clock Tower roundabout with its associated development. The buildings above fronted onto this new road.

The first of this group of three images, in monotone, shows how the road appeared in 1956, the photograph looking approximately south-west. The old Customs House with goods stacked in its yard is on the left, adjacent to the Police Station out of picture. I believe that the development to its west is the Al Mana residence from which that family carried out its commercial business. The photograph was taken from the roof of a government building for the Ministry of the Interior, I think associated with Customs.

The second photograph was also taken on al-Jasra Street – the name later changed to Abdullah bin Jassim Street – this time in March 1972 and from a position on a parking bay at the right hand edge of the first photograph looking west. Qatar National Bank is on the left and the shadowed façade of the Diwan al-Amiri can be seen as the focus behind the small Darwish masjid at the end of the street.

The third image was taken on a morning, some time in the 1960s, and is a similar view, but from slightly further east. The railings enclosing the Central Police Station railings are on the left and the building in the centre is the Chartered Bank building.

This image was taken in April 1972 and looks west down the full length of al-Jasra from Jabr bin Muhammad Street with the Diwan to be seen in the top right corner. Government House is just out of picture to the right and, on the left there is a sub-station behind which was the animal market. The brown single storey building was the fish suq al-samak, or fish market and, behind it was the two-storey Central Post Office. Incidentally, although I have called this street al-Jasra, I believe it is now known as Abduallah bin Jassim Street.

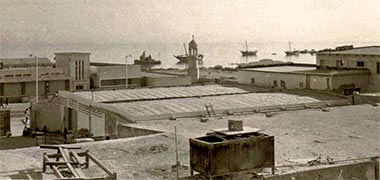

Taken in 1957, this photograph illustrates the link between the enlarged jetty and the suq, as well as the prominence of the merchants’ properties that lined the old littoral, and on which the al-Jasra Road was constructed. Note how the sea is being filled to create more, and valuable, land as well as getting rid of the irregular shore line and shallow waters. Tied up to the west side of the jetty can be seen lighters or barges used to transport goods from the large ships standing out in the roads to the shore.

This photograph is very similar to that above but appears to have been taken a little while prior to it. The shore line in the photograph above can be seen to have been developed through reclamation and the boats drawn up on it here, are no longer present. The area reclaimed on the right of the photograph above was developed by the Darwish family with a masjid and their Cold Stores established opposite the main entrance to the Diwan al-Amiri.

This aerial photograph was taken in 1947 according to the date written on it, and looks down on Doha from the south-east. Comparing it with the square photo six photos above, suggests that it might be earlier than that as the latter shows a constructed jetty. Perhaps it is more likely that the above photograph was taken later than was reported in the source from which I took it. At that time the wadi from the hinterland brought water through the suq in winter but was also the main access route through the suq to the sea and jetty. This is a common system for the location of routes not only in the Persian/Arabian Gulf, but elsewhere in the world, though has the disadvantage of creating difficulties in the rainy season both for those using it as a route as well as for those living and working immediately adjacent to it. This was certainly the case in Doha where winter rains caused significant problems.

This aerial photograph of the centre of Doha was taken in 1949 and looks approximately south or south-east over the developing centre. The al-kuwt, the Turkish fort established by the Ottomans to control Doha, can be clearly seen and in front of it the main maqbara for Doha. A little way to the right of the al-kuwt can be seen the open air eid prayer ground surrounded by a low wall. The dark diagonal line across the top of the photograph is, I believe, a track leading to the important development of Wakra and on to Umm Said, where development was starting relating to the export of oil.

Many years ago I wrote that I had thought this first of two similar photographs was also taken in 1947, but then believed it was made a little later, perhaps 1950. But a second photograph has appeared, bought in the suq with, written in Arabic, ‘Year 1947’, suggesting it was, indeed, taken in 1947. Of much better quality than the first image, the second photograph appears to be a crop of the first photograph.

Taken from the north-west, the covered suq can be seen to the west – left – of the wadi with the main maqbara behind it. Note that there is a simple foot bridge over the wadi. At the south side of the maqbara is the al al-kuwt fort. On the sea front can be seen some of the compounds of the major merchants of Doha who had established themselves near to the shore where their goods were landed. Four small local boats sit by the shore, used to transfer goods from larger craft unable to navigate closer due to the shallow waters. There are more detailed photographs of this area on the Gulf architecture page, apparently deetails from the same image.

The fifties saw the beginnings of development along Doha’s foreshore. This first photograph is from 1955 and looks south-west towards the rise on which the Diwan al-Amiri was developed on the site of Sheikh Abdullah’s complex which can be clearly made out on the higher ground behind the dhow. On the left of the photograph is the manara of the Sheikhs’ mosque.

The first of these three photographs of parts of Doha was taken in 1958, and is of the site where the Darwish offices were constructed at the north end of the suq with the dhow jetty to its north and the Police station to its west. There is evidently considerable building activity with a stockpile of concrete blocks in the foreground. Interestingly there are also two prominent piles of mangrove poles, normally used in traditional buildings as danjal or floor joists.

The second photograph was taken in 1960 looking over Doha to the north-west. The old palace compound of Sheikh Abdullah in feriq al-Salata can be seen to the right silhouetted against the sea. Behind it is the area in which Doha port was developed in the nineteen sixties and later. One interesting aspect of the photograph is what appears to be the beginning of structured residential development to be seen in the right foreground of the photograph, though much of the rest that can be made out follows old tracks. In those days, of course, there would have been little commercial development in these areas, most being concentrated in Doha’s central suq, though there were local shops providing a service reinforced by travelling salesmen selling everything from water and oil to clothing, materials, brushes and the like.

The third photograph is a detail of the second and shows a group of residential compounds in feriq al-Hitmi. The compounds, being on the outskirts of the feriq are relatively spacious and well developed. One or two of the compounds incorporate covered verandahs, but it is surprising to see so many rooms without them. Note that there neither two-storey development as there was at al-Wakrah, nor any badgheer to be seen, indicating that this is was not a well-off area.

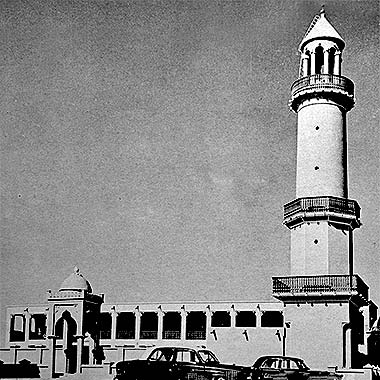

There is more written about this particular photograph of a building on one of the Gulf architecture pages, as I now believe it to be a significant and important structure. The photograph was taken in the 1950s and appeared on the cover of a booklet published in 1977. I believe the structure to be the al-Qubib masjid, also known as the Qassim bin Muhammad al Thani masjid. If I’m right, it was demolished and another masjid took its place, also known as the al-Qubib masjid or, more familiarly as the ‘pigeon’ masjid, itself also demolished. The term qubib refers to dome structures and, as you can see, the masjid must have been the first, if not the only, early masjid to incorporate domes over its musalla. Just as impressive is the gadrooning applied to the top of the manara. This would have been the view south-west from Al Ahmed Street.

I am unsure as to whether this photograph and the next two below are of the al-Qubib masjid, though they are two of the earliest photographs of Qatari architecture I have come across. Compare this photograph with that above it, this being taken looking, more or less, north-east and appearing to show a feature on top of each cupola that seems not to be present in the upper photograph. Moreover, the top of the manara appears to be different in that it appears to be taller in the upper photograph. Nevertheless, the south-west corner feature of the masjid is clearly defined, along with the haunching at ground level, as is a run of pointed arches on the south wall of the courtyard. There appear to be ventilation openings at a high level of the musalla as well as the standard maraazim to shed water from the roof.

Here is another view which includes a masjid with domes across its roof. This time the masjid appears to be the same one as that above it as can be seen in the enlargement in the lower of these two photographs. The upper photograph was taken by the German traveller, Herman Borchardt as he was travelling through the Gulf in the winter of 1903 and Spring 1904. The view appears to have been taken looking west or south-west from feriq al-Salata where there are a variety of boats, notably the bateel and baqaara prominent among them, drawn up and propped along the foreshore. The al-Qubib masjid – if it is that – stands out in the background with little construction of a similar height to be seen around it. The masjid must have been an impressive sight in those days. The masjid was located east of the centre of Doha and west of the palace complex of Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim.

Fifty years later, this is how the al-Qubib masjid looked from the air in 1952. Taken from a larger image, the photograph lacks a little clarity but it shows that a large building, most probably a majlis, has been built outside and to the east of the north-east corner of the of the masjid. The building can be seen to have four bays suggesting that it is larger than the usual constructions which reflected the normal span of their supporting beams at three bays. The sea shore occupies a similar position as it did fifty years previously and a number of buildings outside and to the south-east have been built or developed into two-storey structures.

Interestingly it was noted that there were considerable problems caused by the rains damaging houses in Doha, and that it was only the al-Qubib masjid that was able to provide protection from the rains. The masjid was rebuilt in its second phase in 1878, its design having come about from Sheikh Muhammad bin Jassim travelling to Zubara to confront those who had taken goods from people under his protection. There he saw a domed masjid and, on his return to Doha, had a design based on it constructed by the architect, al-Halimy, but twice the size. The view of it in the photos above would, therefore, be the expanded version of it.

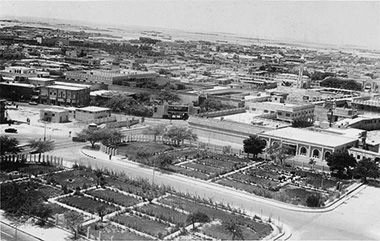

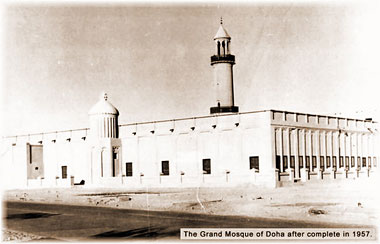

Here is an aerial photograph displayed to the public on the fencing around the Municipality building, late 2011. Reading it, together with the photograph immediately below, would suggest that it was taken at the end of the 1950s or the early 1960s. The edge of the bay has been filled to the east of the country craft jetty and a small road created. Although this image is too small to see, the Vegetable Market, Shari’a Courts building and Ministry of Education have been constructed but the General Post Office and Fish Market have yet to be built to their east. The Darwish Fakhroo office have not yet been constructed. The outline of the Diwan al-Amiri appears to be in place, as is the road arrangement from the Rayyan Road around the Diwan, the Grand Mosque and Clock Tower.

I would guess that this aerial photograph was taken in the early to mid-1960s. Doha’s suq waqf and the fishing jetty are off to the right. The long building is the Ministry of Education, the building to the right or west is the Shari’a Courts building and the building on the left is the main Post Office. On the left of the photograph is a part of the animal market separated from the Post Office by a road. Note that there are buses parked on the road beside the sea as well as boats drawn up. The land here has yet to be filled and Government House constructed on the left where the small local craft sits in the water. Compare this photograph with this below.

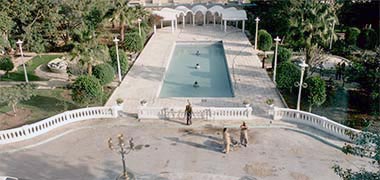

This is another of the aerial photographs displayed to the public on the fencing around the Municipality building, late 2011. In this photograph Rumaillah Hospital, Government guest houses and the Guest Palace have been built as has the Diwan al-Amiri development. Land fill from the country craft jetty to the east, in front of the site on which Government House would be constructed, has not yet started which would place the photograph at around 1965.

This photograph is of the Shari’a Courts building, viewed from the north-west. Constructed in the 1950s it owes its architectural style obviously not to local traditions but to the Western colonial architecture being built in hot and humid climates. Having said that, the brise soleilwere, and are, a sensible way of creating a degree of privacy, stopping sun striking the inner skin and spaces while allowing air to move within and around the building.

The Central Post Office building was an important step in the organisation of communications in the State. This photograph of it would have been taken in the late 1960s or early 1970s and is of its north-east corner, taken from the road. Its entrance can just be glimpsed. The surrounding wall to the right, which also wrapped around the west side of the building, contained post office boxes as there was no delivery system in the State, all mail either being picked up from the keyed boxes or, in the case of the larger commercial and government organisations, being picked up by messengers.

The first of these next three photographs was taken in 1968 of the centre of Doha and shows that about one hundred metres has been added to the shoreline at the north end of the suq. You can gauge the distance to some extent by comparing the relative positions of the graveyard – the large open space in the top right of the photograph above. At the north end of the wadi musheirib you can see, just left of centre, a large construction which was the offices of the Darwish Fakhroo family, one of the country’s major merchants. The beginning of the jetty development can be seen at the foot of the photograph.

The second photograph was taken a year later and is labelled as having been taken from the roof of the Finance and Petroleum building – originally known as Government House – in 1969. In the distance on the skyline the manara of the Grand Mosque can be seen and, to its right, the Diwan al Amiri, its north end being the blank wall with four openings in it in which, I understand, two similar residences were to be constructed. In the middle of the left edge of the photograph can be seen the Darwish headquarters building.

This third aerial oblique photograph, taken in October 1972, which looks south-east over the north end of the suq. The large office building in the left foreground is the Darwish Fakhroo main office with, I believe, a pumping station in front of it and, with its west end on the edge of the photograph, the recently constructed vegetable suq. In the right foreground is the central Police Station behind its security fence. Behind them is Doha’s main suq with the structures covering the internal sikaat clearly visible on the right.

With Doha’s road infrastructure starting, the first major new building was constructed by the government based on its need for offices to house the administration increasingly required to run the country. A number of smaller offices were built to house the new Ministers and their necessary operations, such as the Ministries of Education, Public Works and Electrity and Water, but a larger, central facility was perceived to be necessary.

Government House was built, I believe around 1967 or 1968, on the newly reclaimed land, north of the old corniche or littoral that runs behind it in this pair of photographs, apparently taken on the same run. Behind the old corniche can be seen the General Post Office, Ministry of Education and the Courts building to the right of Government House and, at the right edge of the photograph, the curved structural roof of the vegetable market. The first of these two photographs, looking approximately south-east, shows the shore a little to the east of the two photographs above it, as well as the end of the small jetty constructed to ease the moving of goods ashore from the dhows and straight into the suq behind it. The second photograph gives another view of this part of the centre of Doha with the east bay overlooked by feriq al-Salata and feriq al-Hitmi visible in the background.

Said to have been taken in 1969, this aerial photograph looks over the east side of Doha towards its east bay. Smoke can be seen coming from the Power Station at Ras Abu Aboud just right of the centre at the top of the photograph. On the left, work on the port has started and much of feriq al-Salata can be seen to have been cleared top left. At the bottom centre of the photograph is the National Library with the road on the left running east to Ras Abu Aboud and, to the left, north past the National Sports Stadium.

To contrast with the above photographs, here is one that gives some indication of the character of activity in the port in 2005. In the nineteen-seventies the port was only able to take four ships at a time and, with the amount of materials being brought in to feed the escalating economy, there were always ships out in the roads waiting their turn to berth. Now the port has been enlarged but the same pressure is on the port authorities to bring materials in and have them dispersed rapidly.

This photograph was taken in 1954 and is said to show the beginning of construction of the port with gabions forming the main structure and rocks being dumped to form the main structure. Looking carefully at the photograph it appears to have been taken from west and is of what was later known as the dhow jetty, the jetty which was established immediately north of suq waqf, Doha’s main suq. I believe the domes of Qassim bin Muhammad al Thani’s masjid can just be seen on the left of the photograph, though I admit that I can’t spot its manara. What is particularly notable is the shallow depth of the sea at this point, a reminder of the dredging that was to come about twenty years later.

The dhow jetty was crucial to the running of the country. Goods were brought ashore in Dukhan and Umm Said directly to their own small jetties, those goods relating to the oil industry but also including staples for those living and working there. But the majority of the country’s goods were carried into Doha from the dhow jetty either directly by dhows travelling from ports within and outside the Gulf, or by lighters used to tranship goods from, usually, ocean-going vessels that were too large to approach the shore – the waters near the shore in Doha being relatively shallow. It was not until the construction of the new port and the cutting of a deep water channel to it that this problem was overcome. In the first photograph, taken in 1954, the new jetty can be seen to have gates at its entrance with either a soldier or policeman on duty on the right. In the second photograph a dhow with its lateen sail up manoeuvres towards the jetty. The photograph was probably taken in the later 1950s or early 1960s.

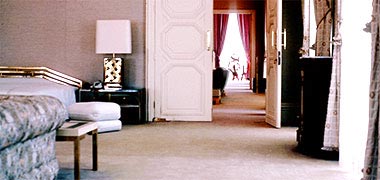

One of the favourite forms of passive recreation in the early days of the State’s development, was the cinema. Mostly visited by expatriates, performances only took place at night as the first cinemas were roofless, a relatively inexpensive way of creating a cinema, though one that was affected by external noises, such as produced by aircraft, as well as creating noise for those living nearby.