a collection of notes on areas of personal interest

- Introduction

- Arabic / Islamic design

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 01

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 02

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 03

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 04

- Islamic architecture

- Islamic urban design 01

- Islamic urban design 02

- Islamic urban design 03

- Islamic urban design 04

- Islamic urban design 05

- Arabic / Islamic gardens

- Gulf architecture 01

- Gulf architecture 02

- Gulf architecture 03

- Gulf architecture 04

- Gulf architecture 05

- Gulf architecture 06

- Gulf architecture 07

- Gulf architecture 08

- Infrastructure development

- The building industry

- Environmental control

- Perception

- The household on its lot

- A new approach – conceptual

- A new approach – principles

- A new approach – details

- al-Salata al jadida

- Public housing

- Expatriate housing study

- Apartment housing

- Pressures for change

- The State’s administration

- Society 01

- Society 02

- Society 03

- Society 04

- Society 05

- Society 06

- History of the peninsula

- Geography

- Planning 01

- Planning 02

- Population

- Traditional boats

- Boat types

- Old Qatar 01

- Old Qatar 02

- Security

- Protection

- Design brief

- Design elements

- Building regulations

- Glossary

- Glossary addendum

- References

- References addendum

- Links to other sites

Development at al-Wakra

The town of al-Wakra is said to have been founded in 1828 but had fallen into disrepair having been abandoned, I have been told by people living there, after the Second World War. This was not the first time, however, as it was also abandoned in 1838 and returned to by its inhabitants in 1842.

This image, said to have been taken in the 1960s, looks south towards Umm Said from the south end of the settlement at Wakra towards the high ground known then as ‘Wakra hill’ or ‘Wakra mountain’ – ‘jabal wakra’. In the foreground is an abandoned masjid, apparently missing its manara. It is possible to see the external steps that led up to the manara.

This first overhead aerial photograph was taken, I think, in the early 1950s. The sand bar protecting the town is highly visible in this photograph. A large maqbara is clearly seen left of centre and it is also noticeable that there are what appear to be abandoned buildings to the north. Development on more orthogonal lines is suggested on the west of the town but the older development nearer the coast has a typical, random structure to it. The state of dilapidation, seen in the photographs below, suggests that it is likely to have begun to fall apart well before the time these photographs were taken.

The oblique aerial photograph shows the town with the road to Doha leading out of the top of the photograph and the square shape of the fort visible in the centre. The sand bar which was beginning to create problems for the boats can be clearly seen on the right. This was an important settlement in terms of its architecture reflecting, I assume, something of the character and importance of those living there.

These two aerial photographs of al-Wakra show a little more of the character of the town. In the first, taken from approximately the south-west, you can see one of its important features, the sand bank which created a natural harbour but which, I understand, slowly restricted its use. In fact, nowadays there is a long jetty to the right of this photograph enabling access to deeper water. I guess this photograph was taken in the nineteen seventies, though I am not sure. It certainly shows a dual carriageway road moving north-south and was the road connecting Doha with the industrial city and oil loading port of Umm Said. The second photograph was taken in 1976 some time after the town was abandoned. Fishermen were still operating here with boats pulled up onto the foreshore and a stone fish trap visible. It is particularly noticeable that the buildings have their major openings, both at ground and first floor, open to the east and sea.

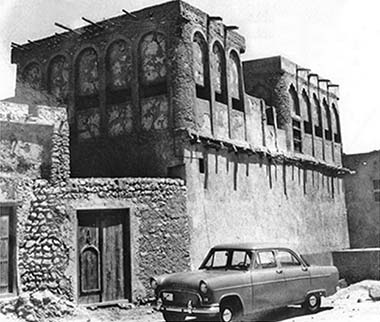

Much of the old residential development near the foreshore of Wakra was of good quality. Typified by its having good proportions, tall internal volumes and being well decorated internally and externally, the buildings formed an impressive group adjacent to the sea even in the early 1970s. However the town was abandoned some time after the al-Bu’ainain left Wakra at the beginning of the twentieth century and the buildings began to fall into a state of disrepair.

In contrast with the better quality buildings shown lower down the page, this small solid structure illustrates a simpler construction which hints at the more sophisticated buildings that were to be developed. The walls are of traditional construction, slightly battered and with sq rather than rounded corners. All five openings are protected by badgheer which suggests the long face is towards the west or south. There are additional openings at the top of the room to ventilate the internal space. There are three maraazim on the long side of the building and the roof line is finished with well-defined decorative shurfa.

From the same source as the image above comes this photograph of the interior of a room in Wakra. It is not the same building as that above and appears to be a first floor room though the floor outside the windows has disappeared.

The room is not tall but has decorative naqsh trims below a plain band visually supporting the shandal roof beams. The window openings are simply shaped and contain wrought iron bars for security as well as wooden shutters. An attempt has been made to close off the open area above the door with wooden boards. The window shutters and wooden doors both open on pintel hinges, the latter having the traditional wooden lock and hasp on it but, unusually, on the inside of the room suggesting that the space on the other side of the door is more important. There appear to be full length windows on the left of the room, but not on the right suggesting that the photograph was taken looking south.

As mentioned above, by the beginning of the 1970s the old foreshore of Wakra was virtually abandoned. One or two of the old houses still had people living in them and the local fishermen continued to use the area for mending their nets and drawing up their boats, even though the sea was silting up and very shallow. A room in one of these houses is shown a little way below where it can be seen to becoming crowded for the occupant. This first image was taken from the left hand side of the image immediately above, looking to the right, or north along the foreshore. The building on the left is readily identified in both photographs.

This second image was taken looking approximately south-west, its location being easily identified from the view of the two-storey building seen on both photographs. Most of the buildings were by that time in a poor state of repair with water beginning to enter those that were still lived in, and some of the walls falling of their own accord without warning.

This old photograph can be compared with that immediately above and evidently is significantly older, suggesting it was taken in the 1960s or even the 1950s. The upper level of the two-storey building is still in use and, outside the entrance door is a small wooden dikka. Oil drums from the country’s burgeoning industry are piled against the wall. What is particularly evident are the number of fishing craft drawn up on the beach. It is not clear to me what function the pole on top of the building has, but it suggests that it might have been used as a sighting point for craft at sea rather than, for instance, a flag pole.

This image is, I believe, of the foreshore at Wakra and dates from the 1950s. A fishing boat can be seen drawn up on the shore at the far right of the photograph, but the building on the left was not there in the early 1970s. It has a very similar design to it as the building shown in the three photographs above it, but it has eight bays compared with those above with seven, and it sits with its long side facing the sea, which is perhaps more logical than the other building in order to benefit from the onshore breezes from the sea.

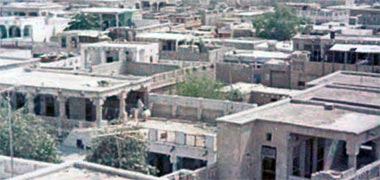

Here are two photographs of the old town of al-Wakra, situated a few miles south of Doha, the first looking north-east. The lower one you can see to be dated 1956, so it is evident that it had been abandoned by that date. However, I can recall people living in al-Wakra in the early nineteen-seventies, and making a small living from fishing, though many were moving to the security of government employment in Doha.

From the evidence of what remains it appears that al-Wakra was a relatively well-off town. Some of that wealth will have come from pearling. I don’t know why al-Khor should appear less well-off as I believe that pearling used to be its main industry. But the buildings at al-Wakra, both in their arrangement and decoration, were some of the best in the country, though also architecturally different. It is interesting to see that there is an ’arish, a pitched roofed building which would have been roofed with palm fronds in the foreground.

In the first two photos you can see a little of the character of the buildings. There were many two-storeyed houses, most of them facing the sea and turning their backs on the west and its hot, afternoon sun and the shamal, protected by badgheer which allowed cooling winds to flow through the building and were capable of being closed in the event of rain or dust storms. The buildings would have taken advantage of the diurnal air movements that flowed from the sea towards the land in the mornings.

Here are four photographs from the early 1970s illustrating something of the character of the buildings at the time of the first studies into the planning of Doha and Umm Said, al-Wakra being between the two urban developments, but there being at that time no planning designated for it. The photographs represent both the state of the abandoned urban centre at that time, as well as the quality of the traditional architecture of the pensinsula.

The first of the four photographs shows a series of the two-storey structures facing the sea to the right, east, in order for those in the upper storey to take the benefits from the diurnal air movements bringing cool breezes in from the sea to the east. These buildings were situated around fifty or sixty metres from the sea; the building on the right of the photograph was situated on the road which ran along the foreshore. This image can be compared with the sepia image above, taken in 1956.

This second photograph was taken from the building mentioned above as being on the front at al-Wakra. It shows the view through its first floor room looking south along the foreshore and its associated development. The sea at al-Wakra was relatively shallow, and although a number of fishing boats can be seen drawn up on the foreshore, the long jetty used to accommodate the larger fishing boats in deep water can be glimpsed through the centre of the photograph.

The third photograph illustrates the relationship of the two-storey element of a residential compound with its courtyard. The first floor structure in this photograph has five bays on its long side and three on its short side and can be compared with the building on the right of the first photograph which has seven bays on its long side and was taller inside. What is interesting to see in all these illustrations is the high quality of the traditional architecture.

The last of this group of four photographs illustrates the character of interior of one of the traditional rooms in a house adjacent to the foreshore of al-Wakra, south of the above buildings, and still inhabited in the Spring of 1975. Many of these small rooms contained naqsh plaster carving, this one having a rich covering of the walls. Note the awtad let into the walls from which to hang guns and clothes in this case. Many of the old buildings of al-Wakra had good quality decorative work carried out on them, both pre-fabricated and offered up into place as well as carved in-situ. There is more on this on a related page of these notes.

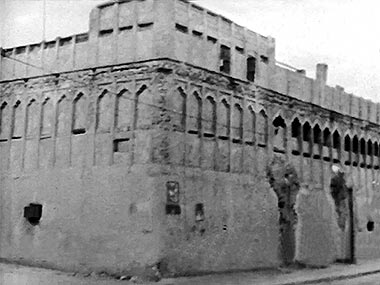

This photograph was taken in 1908 by Major Percy Cox, the British Political Resident in the Gulf, and is a very early illustration of the qal’at at al-Wakra. While there is not a great deal of detail visible, there is sufficient to show that it was taken from around a hundred metres to the east of the qal’at with, on the right and to its north, the masjid of Sheikh Abdulrahman bin Jassim al-Thani, the head of that part of the al-Thani family. The masjid, unusually, appears to have four bays rather than an odd number as the latter permits the mihrab to fall in the centre of a bay rather than on a column line. The photograph also suggests that there was only a single circular tower at the time of the photograph, that being in the north-west corner of the qal’at.

Development at al-Khor

Sitting in a protected natural harbour on Qatar’s east coast, al-Khor used to be known as a fishing village and, as such, it seemed to have a very different character from the other littoral developments, particularly as it was built on an inlet – from which it took its name – and because the land was significantly raised when compared with the urban developments at Bida, Doha and Wakra to its south. The first view looks approximately north-east over the town, illustrating its relationship with the marine inlet, or khor. The police post can be seen as the white building top centre.

This view west along the foreshore shows how it looked in March 1972 just before the town was razed to the ground as the inhabitants wished to develop a Corniche along the shore line and benefit from new housing to be constructed to the south-west. The iwan of the main masjid can be seen towards the right of the photograph with its distinctive battered manara rising above the skyline. While the surrounding development was demolished, the masjid remained and associated with new landscaping.

This next image shows the old Police post at the eastern edge of the shore at al-Khor taken, I believe, in the 1950s, though I’m unsure of the date. The situation of the post was carefully selected as from it there were views over the khor to its west, a degree of supervision across the khor to the north, as well as over the sea directly to its east. Immediately below is a photograph taken in March 1972 for comparison.

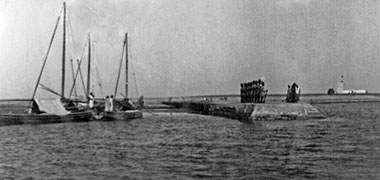

One of the difficulties facing the fishermen was the relatively shallow waters of the khor, though this was a similar state of affairs at Bida, Doha and Wakra, the latter not being helped by the gradual silting of its foreshore. Because of this problem, the fishing fleet was usually moored nearer to the entrance of the khor, and only those craft requiring maintenance brought into the town and drawn up onto the foreshore.

In this image of the foreshore, also taken in March 1972, it is possible to see something of the problem for the fishermen with the shallow water, as well as the large number of tyres dumped into the waters. It is possible they had a function but, if they had, I’m unsure what it would have been.

Here the fishing fleet can be seen riding at anchor in the shallow waters of the khor north-east of the town. Although the colours of the image might look a little unnatural, they do represent the colours of the shallow waters seen around the Qatar peninsula. It was also possible to see dolphins playing in the khor, and perhaps still is.

The first group of images above, with the exception of the second, sepia, image were taken in March of 1972. Three years later, in March 1975, this next two images were taken and show that while the buildings had mostly been demolished, no new development had yet been created in the previous three years and the Corniche was still in the planning and design stages. Regrettably I don’t have an image of the old burj or watch tower which stood on the high ground at the west end of al-Khor, but the lower part of what was left of the burj can be seen above one of the partially demolished houses on the skyline.

The simple manara of the small masjid which sat near the water’s edge remained for a number of years, serving as a reminder of the old development while repairs were made to country craft around it. The small manara was eventually taken down when the new Corniche was developed.

Development at al-Rayyan

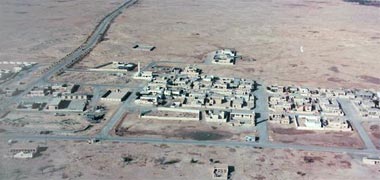

Elsewhere I have mentioned the town of Rayyan as being one of the centres where members of the al-Thani family settled within the peninsula. Regrettably I have no old photographs of al-Wukair, west of al-Wakra, where there were also members of the al-Thani family living, but this photograph is likely to be of one of the al-Thani residences in Rayyan. The second of these two photographs, a detail of the first, suggests that it is the same development as that shown in the RAF photograph a little lower down the page, this photograph being taken looking approximately south-west. The settlement was evidently a very small settlement in 1937. Members of the family also settled in other areas of the peninsula, particularly to the north of Doha. There are illustrations of developments at Umm Salal Muhammad on the preceding page and elsewhere.

This area to the west of Doha is today, and was then, a favoured area of the peninsula where the al-Thani family located a number of their settlements. In the photograph above you can see how the families are likely to have developed their housing around the little arable land existing in that area, particularly grouping themselves next to the large enclosed structure which can be seen in the centre of the photograph. Bear in mind this was only seventy years ago at the time of writing – or just two generations.

By way of contrast, the third of these photographs is an oblique aerial photograph taken in the mid-1960s, looking approximately west over Rayyan. The fort can be seen at the top right, with a number of Royal residences on the left. The road leading out of the top of the photograph travels past the north side of the development at al-Wajbah on its path to Dukhan on the west coast of the peninsula. The compound shown above is out of the top of the picture, approximately 1.8 kilometres east-north-east of the fort.

This next aerial photograph was taken from the opposite direction from that above, approximately the north-west, in August 1976, and shows the fort in a little more detail.

These two photographs are of the entrance to the residence of a previous ruler, Sheikh Ali bin Abdullah at Rayyan. I believe the first was taken in 1966 and is the fortified development in Rayyan, now apparently known on English maps as Rayyan Castle. The gate is located on the north corner of the east face of the development. This corner of the fort is the only one without a circular, or any, tower located there, and leads into what is likely to have been the more public offices associated with his rule of the peninsula.

The second image is likely to have been also taken in the 1960s and has been developed from a still image and placed here as it shows a very typical arrangement of the military providing protection to the Ruler, the open vehicles waiting outside the main gate, the personal, badu guards having entered with the Ruler.

Although there is lip-service paid to the traditional architectural character of the peninsula in the durwa detailing to the top of the wall and the dikka along its base, the fenestration and what appears to be protective metal grilles, are imported design features to the peninsula. It would be interesting to know where the architect came from as Sheikh Ali’s father’s development in feriq al-Salata was designed by a Bahraini master builder in a very traditional style, admittedly earlier than this development.

It is possible to see in this aerial plan of the development the shadow of the burj of a masjid located directly opposite the entrance where the ruler and guests would have been able to join together in prayer. The orientation of the walls of the fort follow that of the walls of the masjid, the inaccuracy in orientation unusual as many of the older masaajid were oriented with their mihrab correctly pointing a little south of west.

Note also that there are, in the south-east corner of the complex, two similar groups of buildings, each organised around a central courtyard. These would have been constructed for two wives, treating them equally.

At this distance in time it is not possible to know the precise purpose of the other buildings within the fort. The central, south entrance leads into a long courtyard with central landscaping, apparently incorporating a water feature as did and do most similar developments. The women’s accomodation is on the right, Sheikh Ali’s on the left arranged around the courtyard in the south-west corner. It looks as if service accomodation is on the west wall with garaging in the centre to the north. The north-west corner is shown empty when the aerial photograph above was retrieved in 2020, but it is likely to have been set aside for a garden with, perhaps, accommodation for animals. Incidentally, the renovation of the fort has seen the removal of the two neon national flags and the shahada shown on this photograph, taken in March 1972.

Since writing the original note on the above development I came across an even earlier aerial photograph of Rayyan, taken by the Royal Air Force in May 1934 when looking for suitable sites for airstrips. The oblique image was taken looking approximately north-west. I have left it here for comparison with the development above, and there are more notes related to it on one of the Gulf architecture pages.

The 1937 image at the top of this section was found on a government site that has since disappeared – though it can be found again with a reverse image search. Regrettably there is not enough detail in the photograph to learn much of the way in which the compound operated, though some can be assumed from similarities with later compounds. Click on the 1937 image to view the original government web image in a separate window.

For orientation, Doha is some way off from the bottom right hand corner of the photograph with a track visible leading between them – around ten kilometres as the crow flies to the al-Kut fort. The fortified development at al-Wajbah is around three-and-a-half kilometres to the west – out of the top left corner of the photograph.

This is a more clear view of one of the fortified developments at Rayyan at that time, five years before the start of the Second World War, a war that delayed the development of the oil fields of the peninsula and, therefore, the State.

The lower image here is a detail of this fortified development at Rayyan shown above in 1934. It gives a little better understanding of the internal layout at that time. There are circular towers on its south-east and north-west corners as well as another circular tower on the north-east corner of the northern extension – though this is not raised to the same height as the two main towers. The main entrance to the development is from the south, left in the photograph, and there appear to be two similar constructions on the far side suggesting they would have been for the Sheikh’s two wives.

There is a little more written about old developments in Rayyan on one of the pages looking at Gulf architecture.

Development at al-Salata

The first of this group of photographs was taken from a British Royal Air Force flight, early in the morning in May 1934. It looks approximately north-west over the East and West Bays of Doha with al-Khalifat nearest to camera, then al-Hitmi, al-Salata and, distant left, Doha with al-Bida beyond it, both facing the West Bay. That part of the littoral in the foreground, al-Khalifat, was given over to the drawing up of traditional craft. Fishermen’s housing was situated immediately behind it along with a masjid and sitting areas, majaalis, some of them existing into the 1970s. The palace development of Sheikh Abdullah is in the centre of the photograph, constructed on slightly rising ground with a number of traditional craft drawn up on the foreshore. This slight promontory is probably the reason that the palace was constructed on that location, around a kilometre and a half from the centre of Doha.

This aerial photograph, probably taken in the 1950s and looking almost due west, illustrates something of the density of development on this eastern edge of Doha at feriq al-Salata with, particularly, an interesting urban feature. The photograph appears to have been taken a little later than that above as there is more development apparent and, comparing the two, shows what might be considered at first sight to be a large masjid which is not seen in the photograph above.

In the detail of the main photograph, the two-storey building in the centre of Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim’s residential development can be seen towards the top right corner of the photograph and that compound appears to be significantly smaller than the one prominent in this detail, and of a different character.

However, it is not definite that the significant development – which appears as a colonnaded structure on two sides of a large courtyard – is a masjid as it seems not to be pointing in the right direction and lacks a musalla and manara. If anything it appears to be a large storage area. A small bay for access to the east bay has been created and there is what appears to be a majlis building incorporated into the south-east corner of the development along with other structures along the south wall. It is not clear what functions are associated with the structures between the courtyard and bay.

This next photograph is said to have been taken in the late 1960s when a lot of the development in and around the furuwq of al-Salata and al-Hitmi still remained, part of the latter being seen in the lower part of the photograph. By 1972, this part of Doha witnessed slow demolition of what was mostly residential development and the beginnings of the creation of the Corniche. A bund was created for the dual carriage road system and the lorries of the Taxi Association began the filling process to create a clear, filled land in this area. One notable element in this photograph is that the power station at Ras abu Aboud can be seen top left of the image.

This enlargement taken from the top left corner of the above image shows something of the development of the power station at Ras Abu Aboud which was inaugurated in 1963 at a cost of a billion Qatar Riyals with, in 1970, a capacity of 60MW.

These next illustrations are here to show something of the setting of the development at feriq al-Salata associated with Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim al-Thani. All four illustrations are from 1952. Note how the settlements lead east along the coast from Doha with the furuwq of al-Salata, al-Hitmi and al-Khalaifat. It should be noted that some members of the al-Thani families lived within these furuwq, presumably due to the location of Sheikh Abdullah.

It seems not to be known why this development was located at feriq al-Salata. Members of the al-Thani qabila lived in a variety of places on the peninsula prior to the turn of the twentieth century. Many of them lived in the north of the peninsula but it is likely that with the increasing importance of al-Bida and Doha and, perhaps, Wakra, it might have seemed logical to move to the centre of international activities which was becoming centred at Doha. The peninsula was surrounded on the west by low waters and the north had significant historical difficulties associated with Zubarah and Bahrain. The east coast enjoyed deeper water and, at Doha, was the location selected by many of the merchants to base their commercial activities and, perhaps as a consequence, by the Ottomans who made it their main policing station.

The site at feriq al-Salata was selected as being immediately adjacent to the sea in the east bay of Doha and was situated at the edge of the feriq occupied, particularly in the north peninsula, by the al-Sulaiti qabila. It can be seen in the central map that it is immediately north of feriq al-Hitmi, the area occupied by that family both of them associated with fishing, pearling and maritime activities. South of its south-east corner was a small masjid which would have catered both for the needs of Sheikh Abdullah as well as those living near him. Interestingly, the land is relatively low at this point and a significant distance from the centre of Doha to its west. Later, of course, the development was abandoned and the seat of the al-Thani moved to the west of the centre of Doha, onto the higher, more commanding and strategically important site where it now stands.

These first four photographs, all taken around 1971, illustrate something of the state of repair of the the buildings constituting Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim’s development in feriq al-Salata at that time. At the beginnings of the 1970s the Government determined they would create what would be named the ‘Qatar National Museum’, so preserving the original development – or incorporating as much of the original buildings as practicable – and changing the character of the complex from one which reflected the family’s domestic and national organisational requirements, to one suited to the organisation, collation and display of artefacts of national interest and importance, while catering for access by the public for their education and enjoyment.

The original grouping of buildings was revised to incorporate a new structure on its north side which would house offices and the artefacts illustrating something of the history of the country, a number of buildings and walls were taken down and the more important buildings repaired or reconstructed as near as possible to their original form and detailing, and with the introduction of electricity, an issue which engendered considerable debate.

This lower photograph, taken of the end wall inside one of the more important rooms of the complex, is perhaps atypical in the greater extent of the damage caused by vandalism. Sadly, much of the traditional naqsh in this and other buildings throughout the peninsula has been lost this way, taking with it our understanding of the character and range of patterns used. Interestingly, the pattern of decoration of the external face of the wall can be seen through the broken naqsh panels.

With the exception of the photographs above, the next group of photographs was taken from two sources, one of them an old government publication on the Qatar National Museum. They date back to the 1930s and illustrate something of the old complex of Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim bin Muhammad al-Thani. Generally referred to as the ‘Old Amiri Palace’ the development was refurbished, mostly accurately and sympathetically, but with the addition of a new building and surrounding wall for security, to serve as the Qatar National Museum in the early 1970s. The site, and the buildings within it, are located with the long axis of the site approximately in line with the holy city of Mecca – a little south of west – and most probably a deliberate decision.

Sheikh Abdullah established the development for his family around the beginning of the twentieth century some distance to the east of the centre of the small conurbation which was Doha. The museum authorities now put the date at 1906. The development was associated with the east bay of what is now Doha. This period of Qatari history had much to do with the competing British and Turkish interests in the Gulf, one of the routes to the Far East, particularly the Indian sub-continent and China. The Turks established themselves in the peninsula with a presence both at al-Bida, north of Doha, but also on the high ground to the south-west of the Doha suq and residential development. The ground between the suq and their qal’at al askar was given over to a maqbara, I suspect a way of keeping relatively clear ground in front of their fortified position.

Something of the north gate house of the residential compound is illustrated in tis next group of four photographs, the first three probably taken around the same time, the first colour photograph having been made in the late 1960s looking down from the central two-storey structure in the middle of the compound. While the palace complex was essentially a residential development, the history of the times suggests that it was necessary to provide a significant degree of protection in mind. The fourth photograph was taken in March 1972.

The gate house structure shows a form of control over anybody entering, constraining the passage in depth – the structure being in the proportions of 2:1 on plan – rather than allowing entrance straight into the compound once through the external gate. The lowest of these three photographs shows the side of the public majlis situated in the north-east corner of the compound.

These photographs illustrate a little of the character of the region at that time, with influences of both the Najd hinterland as well as that of the Gulf littoral where the influence of sea breezes and environmental considerations are reflected in the structure, character and detailing of architectural designs – the development having been designed by the Bahraini master builder, Abdullah bin Ali al-Mail. In particular, this form of architecture integrates structure, environmental and decorative treatments to a considerable extent. Despite the Bahraini influence the character is, however, Qatari, with slightly finer elements used in their construction compared with the heavier styles of the hinterland.

This photograph also shows the north gate to the compound, this time viewed over the building knowns as the little majlis, which also was the coffee reception hall, an important element relating to hospitality and the public majlis. To the right of the photograph is the public apartment associated with the north gate house. The four elements of the north gate house, the east gate house, the coffee majlis and the public majlis constituted the main elements of the compound associated with the public functions of Sheikh Abdullah.

There were three entrances to the residential complex of Sheikh Abdullah, I believe, these being on the north, east and west sides of the surrounding wall. The subsequent development of the complex into the Doha National Museum must have amended this to create an entrance on the south side, while omitting the west entrance.

The first two photographs show the east entrance from within the compound, this opening in fact facing north-east, looking at it from the south, the gateway facing directly onto the central two-storey structure in the centre of the compound.

Given the importance of this gateway, it may seem a little surprising that it bears only minimal decoration with a small number of carved roundels and lineal decoration outlining the arch. The second photograph gives an indication of the carving of the architrave and six rosettes, while within the gateway can be seen a naqsh panel, unusually a triangular framework with a central rosette. The third photograph is a general illustration of the entrance from outside the compound, facing north-east to the sea.

It should also be borne in mind that Sheikh Abdullah, as the Ruler of the country, was involved in affairs of State, commercial dealings as well as social and cultural issues. In this he brought to this development many of the social characteristics of the badu, creating a complex that, within a wahhabi tradition, would have been surprisingly open with women having considerable freedom within this complex.

Around 1923 Sheikh Abdullah left this development and moved to the other side of Doha where he developed a larger palace complex on the high ground overlooking Doha’s suq to its east and shown on the previous page. This group of photographs illustrate how the group was allowed to deteriorate. The first and third photographs were taken around ten or fifteen years after he left, the lower three most probably in the late 1940s. That above shows the western entrance structure to the compound and was located in the west wall adjacent to the majlis which was in the north-west corner of the complex.

This sepia photograph, an enlargement of a small image, is an aerial photograph taken from the north, approximately the reverse angle of the photograph above it. The photo shows the northern corner of the complex with the north and east gate structures clearly visible. By the time this photograph was taken, it is interesting to note that there is development relatively close to the eastern wall of the compound, presumably because Sheikh Abdullah had moved to the new development west of Doha. The photograph also illustrates the character of the complex with single-storey buildings contained within a surrounding wall and a tall, two-storey building at its centre where he and his family lived, other buildings being lived in by the families of Shaikhs Hamad and Ali, and supporting the life and work of Shaikh Abdullah.

Taken from the reverse angle from that of the sepia image above, this next photograph appears to have been taken a little later by the evidence of the state of the buildings within the complex. It shows that the beginnings of a fill operation have started on the littoral. This was the start of the decision to clean up the foreshore which displayed a natural mixture of sand, rock and coral and where boats were traditionally beached. With time the area where the sea is in this photograph was filled in and the Corniche started. This exercise beginning in the early 1970s.

Sheikh Abdullah developed his complex as a discrete compound, partly fortified with high walls and watch towers as was the custom in the region. In the centre were his family’s living quarters and, on the north-west corner a majlis or meeting room where he was able to carry out affairs of state as well as his personal business. In those days there was about a mile between the centre of the suq and Sheikh Abdullah’s development, situated at the north end of feriq al-Salata, the land traditionally belonging to the Sulaiti qabila. With time the development was enlarged to provide houses for his two sons, Sheikh Ali and Sheikh Hamad. This development served not only as his family’s home but, in the traditions of the area, as the centre of his work as governor of the peninsula, the Turks having left in 1916 and the British taking their place.

These three photographs show something of the palace complex of Sheikh Abdullah as it was in 1960 over some of its surrounding buildings in feriq al-Salata. The views, looking approximately north and north-west respectively, show the haphazard urbanisation to the south of the complex as well as its relationship with the sea. Many of the family who inhabited this feriq – as well as the feriq al-Hitmi, adjacent to and south of the complex – were associated with the fishing and pearling industries. By this time Sheikh Abdullah had moved to the other side of Doha and his complex had fallen into disrepair. Apparently, much of the surrounding area has also been abandoned by the time this photograph was taken. The irregular configuration of the coastline is evident, a masjid can be seen on the cost behind the complex.

This image was developed from a video taken in the 1960s and shows an oblique view of the complex, particulalry illustrating the masjid adjacent to the east corner of the complex – at the centre left edge of this photograph. A partial reverse view of the masjid can be seen a little way above. It is noticeable that in this image the masjid appears to be painted, suggesting that it was still in use for those living nearby in feriq al-Salata at this time, there being a larger masjid a little way to the west, perhaps the local Friday masjid.

This photograph is taken looking approximately in the same direction as that above, gives a better idea of the location of Sheikh Abdullah’s palace complex in context not just of feriq al-Salata and feriq al-Hitmi, but also with respect to Doha which was developing to its west. The area in which the Port was beginning its development can be seen, its location being fixed by this point being relatively close to deep water – although dredging still had to be carried out to make a safe channel to the extended port. I don’t know what the large area in the right foreground was. If anybody does, I’d be grateful if they would let me know. It was taken in the 1960s.

Members of the family of Sheikh Abdullah also had their own quarters and lived within the compound, there also being a masjid outside and to the south of the south-east corner of the walls which would have served their religious needs as well as of those who were living around the complex. This first photograph is of the west, external facing, façade of the living quarters of Sheikh Ali bin Abdullah. Situated on the west side of the complex, the tower formed, in effect, the north-west corner of the overall compound. Note the considerably sized terrace at first floor level which would have been used particularly on summer nights when it was more comfortable to sleep on the roofs rather than in the hot interiors of the buildings. The lower photograph looks at at the same corner, but from the north-east.

The central building in Sheikh Abdullah’s complex was a two storey formal structure, photographed here as it was in 1967 in the top photograph and, perhaps, in the same year for the lower photograph. The two photographs show the south and west faces of the building respectively. This was the family residence of Sheikh Abdullah, supplemented by a group of rooms arranged around the external wall of the complex and to the south of this building.

Constructed for Sheikh Abdullah in 1918 by the Bahraini master builder, Abdullah bin Ali al-Mail, its architecture based on contemporary modern buildings in Bahrain. Its design importance lies in its central location, a building of height to be experienced in the round, as well as in the logical disposition of its rooms around a central space on two levels, the lower having rooms or covered spaces, the upper constituting an almost continuous gallery. Its location within the compound together with its height will have allowed it to take advantage of the littoral sea breezes, in a similar manner to which the public, single-storied majlis, located in the north corner of the complex, was able to provide to those sitting within it.

This next group of photographs might not be considered to be related to the general subject of this page, the old constructions of the peninsula, but were taken in 1975. The purpose of placing them here is the obvious one – that they can be compared directly with the earlier photographs on this page.

The images – with the exception of the second one – were taken just after the restoration of Sheikh Abdullah’s compound with its reinvention as an exhibit within the Qatar National Museum, which opened in 1975. In that design the opportunity was taken to introduce levels, water and planting to create what was intended to be a more modern, landscaped setting for the old buildings. There are photographs illustrating something of that development on another page.

By contrast, this second photograph was taken in April 2019 and shows the building in its relationship within the compound associated with the new Qatar National Museum. The photograph was taken from a little closer than that above which accounts for the slightly different perspective and proportions.

It is evident that an attempt has been made to return the building to what is likely to have been its original state with regard to its surrounds than when redeveloped for the first version of the Qatar National Museum. The landscaping of that first intervention has been stripped back and the ground cover is now more likely to be similar to that which was originally laid within the compound of the old development. What that was is difficult to recall. It may have been a mixture of the compacted natural soils together with shell sand which was a popular finish in important areas or occasions.

Unlike many of the smaller buildings on the site, the central structure of the development lasted relatively well from its construction to its reconstruction almost sixty years later. Designed on a grid of six by four bays, this allowed the central majlis to be two by four bays in its proportion. No amendments were made to the basic form of the building other than the addition of an enclosure at the top of the stairs giving access to the roof.

It has been explained elsewhere that the ceilings of rooms were generally left with their essential construction exposed, some care being given to the interweaving of the visible elements, with some of the canework being painted with the primary colours then commercially available. This was particularly true for the hassira and basjeel elements of the ceiling, and gave rise to the typical linear or criss-crossed patterns found above the structural shandal beams, some examples of which can be seen on another page.

Contrasting with those examples, these two reconstructed ceilings were photographed in, respectively, the ground and first floor rooms of the central structure in Sheikh Abdullah’s complex at feriq al-Salata. As such they replicated what had been there previously in terms of their structural vocabulary, with trimmed boards used to hide the ceiling construction and being subsequently decorated with paint. More importantly they illustrate the top end of the design market in those days as the flat timbers used to close in the ceiling structure were expensive.

Some levelling through of the structural, but usually irregular, shandal beams was necessary in order to obtain a level ceiling, with the ceiling beams running the length of the space at right angles to the shandal beams that spanned the shorter distance between the long walls of the space. The ceiling boards were finished with gloss coats of paint and then decorative patterns were applied.

As can be seen, the patterns are not those you might anticipate in the peninsula, that in the first floor ceiling appearing to be from a completely different mindset.

At first glance the geometry behind the three main rosettes in the ground floor ceiling appear to be similar to the simple naqsh panels seen within the building and others in and around the complex – yet, they are not. None of them is regular and, while the centre of each is divided into ten, the next circles have seventeen parts, and the outer geometry twenty. It is difficult understanding why this should be so. There is a little more written about these geometries on one of the geometry pages. The triangles in the corner of the ceiling have four circles, the main one having seven divisions, two of the others have four and the last has six divisions.

Contrasting with this, the first floor ceiling has little in the way of a coordinating geometry but appears to have been designed by somebody with no understanding of the design history of the peninsula. Both these ceilings were completed in the early 1970s.

Compared with much of the developments refurbished later, the exterior was kept free of naqsh embellishment, a decision which enables the building to retain much of its feeling of strength in its massing. The columns with their screened bases and arches are visually strong and contrast strongly with the more delicate inner wall with its windowed openings and naqsh panels as can be seen in this view down the long side of the first floor verandah.

Regrettably, though perhaps understandably, most of the original naqsh panels were destroyed through vandalism. Even more sadly to me, this meant that the geometric patterns of the panels also disappeared with the consequence that the knowledge of how they were set out being lost to us. This first photograph shows one of the ends of the main room and illustrates the extent of the damage.

When the decision was taken at the turn of the 1970s to create the Qatar National Museum on the site of Sheikh Abdullah’s compound, the new buildings housing the museum and its artefacts were inserted as an intervention on the west side of the grouping where it was considered that the least change to the existing grouping would be made. Although the original main two-storey structure was standing in the centre of the complex, much of it was stripped back in order to safeguard the reconstruction. In the first of these two photographs, both taken in March 1972, the original juss and hasa can be seen to be reinforced by the use of cement on the lower levels of the main structure. The lower photograph illustrates work on the development mid-way along the south wall of the complex.

Not only was cement used in the construction of the building but it was also part of the mixure used for the naqsh panels decorating the walls of the two main rooms of the building. Here, in a photograph taken in 1972, workmen are still engaged in the process of modelling the walls while naqsh panels have already been incorporated below their work. Notice that the corner of the ceiling has yet to be added.

Here is a view of part of the finished room taken just prior to its formal opening in 1975. This is, I was told, an honest reconstruction of its original form and decoration – with the exception of the fluorescent strip lights visible at the high level. The issue of introducing electrics in both the forms of lighting and air-conditioning into traditional buildings was a problem for many of the builders who, generally, felt it to be anachronistic. The issue is considered elsewhere.

This photograph shows the remains of the public majlis of the complex, the formal meeting room in which the men of the family would meet, discuss and make decisions on a daily basis. It was the public face of the Sheikh Abdullah. It appears to be relatively low due to the construction above the panels being missing. It was situated in the north-west corner of the complex, this photograph having been taken from inside the complex to the north-west. It is the nearest building in the square sepia photograph a little way above, and can be glimpsed in the photograph above that one over the entrance structure.

Seen a few years later, at the end of the 1960s, the east bay and early form of Doha’s port can be seen above and through the public majlis in these two views. The port development effectively defined Doha’s east and west bays. The close proximity and relationship of this north end of Sheikh Abdullah’s complex with the sea is particularly noticeable, and those using the majlis with its shutters open would have been able to enjoy both the view and the littoral breezes coming off the water. Regrettably, as was the case with many of the old, abandoned buildings, a significant amount of damage was done to the naqsh plaster decoration inside the rooms. This photograph of an interior corner of the majlis shows how the panels were placed in pairs within the structure of the building.

The form of the structure is plain to see and formed the basis of most buildings in Qatar. It is of trabeated, or column and beam construction, the columns being provided by hasa, desert stones set in a juss limestone mortar with horizontal timber beams between them. Elsewhere i have written about this in more detail. Decoration has introduced non-structural round-headed and ogee arches, but these are purely decorative and act as relief and contrast to the rectilinear construction. They make no structural contribution to the structure.

This pair of photographs were taken in the 1960s, I believe at al-Salata, and show a little more of the character of the development to the east of Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim’s complex, adjacent to the sea. The first looks along the coast towards a masjid that sat near the sea to the south-east of Sheikh Abdullah’s compound. The local craft have been pulled up onto the beach for protection and, perhaps, maintenance. The lower photograph looks inland from the sea and illustrates a typical street, notable for its width. In the foreground is a craft I believe to be a shuw’i, similar in many respect to that illustrated here, but with a noticeably different prow. The houses are simple structures lived in by those making a living from the sea and, in the distance, a pitched barasti roof can be seen protecting a building.

Finally, here is a photograph of an old masjid at feriq al-Salata. It has the characteristic features of the old masaajid of the peninsula with its short, stubby manara with its heavily battered sides and a six-divisioned opening at its flat-domed head. The musalla has five divisions created with simple columns and a covered area for ritual wudhuw’ has been provided opposite the manara. A simple screen has been constructed at the facing, east, end of the complex, with pyramidical caps to short columns providing stability to the screen.

The central area of Doha

This first image is said to be a view over buildings of Doha, taken in the 1940s. It is not possible to know which part of Doha this was, but it is interesting to see that, on the left hand side of the picture, there is the remains of a single storeyed structure which had a pitched roof. Behind that simple structure is the roof of a large building, punctuated by a number of maraazim. The buildings on the right of the photograph appear to be of a good standard of design, and might be similar to those at Wakra. Their orientation suggests the sea would be to the right.

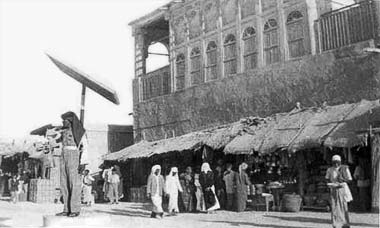

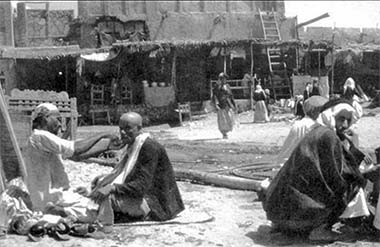

Previously I noted here that there seem to be few photographs illustrating the early days of the central area of Doha, particularly suq waqf as it is now commonly termed. However, I have now found three that were taken very early on and which illustrate something of the character it had in its early days. Both of these black and white images have been worked on in order to make them a little more comprehendable, and there are links to the originals found on a correspondent’s pages. It is not possible for me to tell which of the two images came first, but the second is noted as having been taken in 1951.

The first image is titled ‘suq sha’abi’, which seems to mean either ‘The popular or people’s suq’, which suggests that it is the main suq that people use. I can’t recognise anything resembling suq waqf, old Doha’s central suq, though I believe that is what it shows. There seem to be a lot of women in the photograph which, in the early seventies, was a noticeable feature. When the photograph was taken I can’t say, but the second image is titled suq waqf, 1951, and it may be possible they were taken around the same time.

The second image was taken looking south from near the top of the suq and shows the traffic policeman standing on his raised platform to direct traffic. The photograph shows no shading device over him suggesting it was not taken in the summer months. It can be compared with the two images a little way below.

The third image appears to have been taken from a similar position as was the first, though perhaps closer to the stalls in the suq. This image is said to have been taken in the 1940s and, therefore, would precede that above it. It can also be seen that the buildings in the background are of different widths suggesting that trhe camera, or processing, has widened or narrowed one of the images. Looking at them closely I’m unable to tell which it might be, though my guess would be that the second seems a little wider, and the first a little narrower, judging by the widths of the ventilation openings.

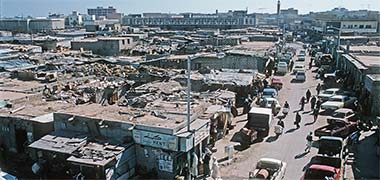

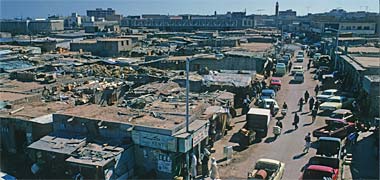

This photograph is a relatively early colour photograph and was developed from an image taken from a Ministry of Information funded book, Qatar, at the entrance to the suq. It is said to have been taken in 1970, illustrating the north end of the suq and looking north. The original photograph was probably taken from the Bismillah Hotel. The photograph two below this one was taken in February 1974 from a point further north than the first photograph. Note the differences.

Although shops were expanding into the area to the right, east, of the image above, the main part of the suq was on the left with the shops in view mainly selling the tools increasingly in demand by the construction industry, though only for small scale works. Some larger pieces of equipment were sold to the west of this part of the suq. Canvas awnings gave some protection from the eastern sun. Backing onto these shops in the covered part of the suq were shops selling lengths of cloth and clothes, both for men and women, and including tailors making up thiyaab both for Qataris and non-Qatari customers. The road is unmade but there is a raised concrete pavement on the left which offered a small degree of protection when the road flooded, the road having been laid along the path of the wadi which led into the sea immediately north of this view and subject to flooding from time to time. There is a brief note on the development of this part of the infrastructure on another page. While the second image is an older photograph dating from the 1960s, it shows the Bismilla hotel at the bend of the road going through the suq having hardly changed at the beginning of the 1970s as the pace of development increased.

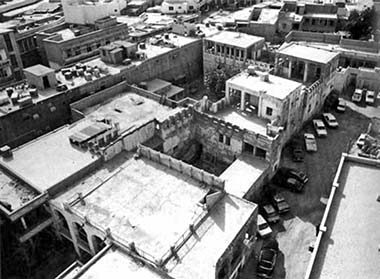

The viewpoint of the this photograph is similar to the third in this series, but from its vantage point I was able to look both north and east. It looks down on the small parking area where the taxis congregated. In those days the taxis were virtually all Peugeot 404s, their drivers being members of the Taxi Association which also governed lorries and trucks. This was a vital part of the economy and supported other related industries. Note how the buildings on the left side of the road have changed when compared with the first photograph of this note.

In those days people still carried out a lot of their shopping on a daily basis in the suq, and the majority of shoppers were men. Many of the shoppers required the taxis to take them and their loads home. Because of this it was relatively common to see taxis overloaded with many passengers or with unusual loads, large cases, tools, jat and goats being regular sights. The second of these three photographs was stitched together from two photographs and looks over what was termed the ‘second hand suq’. In the third photograph, the two-storey modern building was, I believe, ‘suq Faleh’ after its owner. Situated some way from the main part of the shopping area it did not receive the same foot-fall of the main suq and I recall it being virtually empty every time I visited it. The two-storey building top left on the edge of the third photograph was the Justice building.

The old suq was an extension to the east of the main suq and was also referred to as the ‘Iranian suq’. Characterised by its labyrinthine layout and construction of temporary materials it was dramatically affected whenever the rains came as the covers were not waterproof and there was no drainage. All kinds of items were sold there, both imported material similar to the articles sold in the main suq, but also animals as well as second-hand items for which there was a market, most probably with the growing expatriate community.

It is probable that the next three photographs of a traffic policeman on duty in the suq were taken on or about the same time. Even though traffic was not as heavy as it is now, the need to have a form of control was introduced in the middle of the last century and was demonstrated by a small number of traffic police located in the suq on small raised stands that gave them some form of protection as well as solar shading.

This first photograph was taken of the north end of Musheirib street in either 1956 or 1957, depending upon which source you believe. Oddly enough, the sun shade appears to be slanting the wrong way and can’t have been that much help to the policeman standing there on duty. I can recall policemen on traffic duty in the early nineteen seventies but can’t remember when the system stopped. Recently this has been reintroduced, but I think it has to do with decisions on tourism relating to the centre of Doha and the reconstruction of the suq. In the background, the white building on the right is the Courts building.

The second black and white photograph shows the junction – leading west and left out of picture past the central maqbara – further south in the suq, with a merchant’s property of significant scale demonstrating the relationship of road to the retail element of the building. The heights of the building’s storeys was a feature of these old buildings and was designed to maximise the amount of cool air that could be contained within the internal spaces during the day and night cycle.

There is a little more to describe this on one of the Gulf architecture pages. I don’t know, but believe that the photographs are likely to have been taken in the 1950s.

The third image illustrates the interest of passers-by in all activities out of the usual, in this case, somebody taking photographs.

The three photographs above suggest that traffic was a hazard in the days of its introduction and increasing use, though this would not be high by modern standards. This fourth, colour, photograph was taken in February 1972, and shows the same Police stand, this time unoccupied, and similar goods to the previous photograph still being sold in the shops behind. Note that, fifteen or twenty years later, there appears to be a similar casual attitude to walking on the road even though there is now a pavement constructed.

The next two photographs were found on an Arabic site which has a number of old images on it taken within the Gulf and Iraq, but just states that the photographs were taken in Doha, with neither commentary nor date. It is possible only to hazard a guess at the date of the first, perhaps the 1950s, and it is unlikely to have been taken in the same year as the second. Certainly the first of them looks considerably older than the second and suggests an earlier time.

This image is stated to be of shops in the 1960s and appears to be one of the minor passages leading down the wadi Musheirib to the central suq – suq waqf. The image is important as it shows the simple construction of the single storey units with their projecting maraazim and shandal of different lengths, the standard construction of their folding timber doors, the use of external space to place some of their bulkier goods, in this case, refrigerators, and something of how the shops were used as informal majaalis for friends and customers. Also of interest are the competing shop signs, one of which advertises a product. Finally, note the simple canvas awnings used to give shade as well as a degree of protection from rain.

The first photograph captures a number of the elements of the suq of the early post-war days, perhaps even pre-war. The unmade pavement, a pair of pack-donkeys and the shuttered shops raised from the ground to avoid flooding were all part of the street scene in the centre of Doha. Of course, this might be an image of one of the minor roads leading to suq Waqf or Musheirib, but the density of people suggests otherwise.

The second photograph looks south in the centre of the suq Waqf on what was the extension of wadi Musheirib. There are a number of cars moving around Doha by this time, with parking diagonally both sides of the main road. The area out of picture to the left of the photograph was where taxis and porters waited for customers, and the covered suq is on the right. The photograph may have been taken in 1955.

Because of the problems caused by rains bringing floodwater into the centre of Doha, a dam was constructed in the 1960s outside the ‘C’ Ring Road containing and diverting rain waters from their movement through the suq on its way to the sea. However, heavy rains still occurred and, from time to time, the dam was unable to contain the floodwaters. Here is a photograph, taken in the 1980s and looking south, of the wadi Musheirib under water. The corner of the Bismillah hotel, said to be the first in Doha, can just be glimpsed on the left of the photograph. The covered suq is on the right and, being unpaved, would have been severely affected by the rains.

This photograph appears to have been taken in the nineteen sixties by the look of the women’s style of dress, and shows a part of the old suq in Doha on Wadi Musheirib and the character of the stalls facing the old street. It illustrates the relatively dilapidated character of the suq in those days. Incidentally, the women’s dresses were considered to be quite improper at the time but, regrettably, this was relatively common…

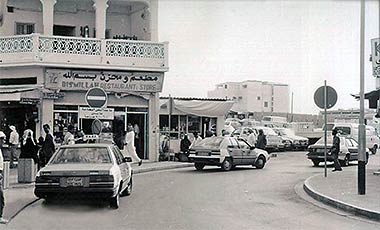

A little further down the street and, by way of contrast, these two photographs are of the Bismillah hotel and restaurant, a new type of building to the country at that time. The photographs were taken from approximately north-east and south respectively, but the first I believe to date from the 1950s, the second from the 1980s.

The building was situated at the bend of the wadi running through suq Waqf and, as such, occupied an important position both from an urban design as well as a commercial point of view. It appears to have been one of the first of the concrete buildings being established in the country.

The trabeated construction is evident, and the detailing has much to do with that of the Indian sub-continent. Open ventilation can be seen and the shaded verandah will also have assisted in keeping the building cool, something which is important because concrete buildings can be extremely uncomfortable due to the retention of heat in the concrete. The introduction of electricity enabled restaurants such as this to install ceiling mounted fans which certainly helped cool the spaces within them.

One of the major commercial companies in Qatar was that of Kassem and Abdulla, sons of Darwish Fakhroo. Their headquarters were situated at the north end of Doha’s suq, opposite and east of the police station and directly accessible to the sea and the jetty. This black and white photograph, taken in 1954, shows their first offices, the structure being a simple development of the beam and column construction of traditional architecture, complete with danjal connecting the columns to provide them with additional rigidity and functional maraazim positioned over the columns. The 1950s offices can be compared with the more imposing structure the Darwish organisation built later, this colour photograph of it being taken looking approximately south-east at its main entrance. The ground floor was mainly taken up with a showroom of large pieces of equipment with most of the offices on the floor above. It reflected the growing confidence of the commercial operations in Qatar, other companies developing offices on a similar scale.

This image, developed from an old video taken in the early 1960s, was taken some time before the image of the Darwish office building directly above. It looks west and shows the office building on the left with a part of the suq fruit and vegetable market to its side. The road runnng from the viewer to and past the office building, Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim Street, fronts the original seashore prior to the Corniche being constructed in the 1970s approximately two hundred yards further north. The country craft harbour can be seen on the right and the Diwan al-Amiri sits on the horizon.

The Darwish family was not the only one with its companies doing business in Qatar though, for decades they were the main one, engaging in a variety of activities associated with the rapidly developing State. One of the other major families that traded in competition with Darwish was the al-Mana family with its similar variety of organisations. In the early days, the 1930s and 1940s they, like Darwish, had a development opening directly onto the West Bay where their goods could be off-loaded from boats and moved directly into their warehousing at the rear, south, within their development. When the road now known as Abdullah bin Jassim Street was established, it was located at what was the littoral edge of the Bay. The road fronted the Darwish buildings illustrated above as well as the al-Mana building, shown here with its attractive balcony, the gateway being that giving access to their living accommodation and warehousing. A small retail outlet was on the right where al-Mana represented, as the sign above the door noted, their Consumer Products Division. Among other important companies, this was the early face of Apple in Qatar.

Although there were at least two banks established prior to 1970 – there are notes on them on another page – Abdullah bin Jassim street witnessed the swift establishment of three or four others.

On the north side of the street and adjoining each other were the banks of al-Mashreq, of which there is another image here and the British Bank of the Middle East, of which there is another image here and, on the south side, the Chartered Bank and Qatar National Bank of which there is another image here, taken in 1972. It was rumoured that Grindlays bank would locate here as well but, in the event, it was established on the Rayyan Road.

Further west, and on the south side of Abdullah bin Jassim street was the Ministry of Municipal Affairs building, also known as the Doha Municipality or baladiya building, the aerial photograph here having being taken in 1972 and the second, lower, image of it being made from an old video recording made some time in the early 1960s.

There is another similar image of this second photograph on the other page recording old photographs of Qatar, which notes a little more of its history, and there is a different old view here.

The building was designed by a British company under the direction of what was to become the Ministry of Public Works, one of a number of early constructions required as the country began to develop with the post-war proceeds from oil.

Further west, and on the south side of Abdullah bin Jassim street was the Ministry of Municipal Affairs building, also known as the Doha Municipality or baladiya building, the aerial photograph here having being taken in 1972 and the second, lower, image of it being made from an old video recording made some time in the early 1960s.

There is another similar image of this second photograph on the other page recording old photographs of Qatar, which notes a little more of its history, and there is a different old view here.

The building was designed by a British company under the direction of what was to become the Ministry of Public Works, one of a number of early constructions required as the country began to develop with the post-war proceeds from oil.

Suq Waqf street was the main road through Doha’s central shopping area. This photograph was taken in 1955 or 1956 and looks north-east along it, the road turning north at the end, towards the West Bay. The suq ’s mosque can be seen centre left. Outside the mosque sat people mending shoes and selling household necessities such as traditional tooth brushes, along with scribes and their typewriters writing letters and legal documents.

This is a view north of Suq Waqf street taken in March 1972. If you look carefully you can see that the building on the left of this photograph is the same building as the one that appears over the oncoming car in the black and white image above. There are two notable features here. The first is that the shops have their ground floor levels raised around half a metre about road level due to the possibility of flooding along the wadi sail, a continuing concern into the 1980s. The second feature to note is the large amount of maraazim on the older building.

The north end of the Doha’s suq ended, effectively, with the Central Police Station on the west side and the Darwish company’s main offices on the east, both of them two storey buildings and visible in the first of these two photographs. By March 1972 when this photograph was taken the suq was a mixture of single and double storey structures, though only the ground floors being used for retail purposes. In the first photograph the open area on the right was used mainly by taxis, the main method by which customers with purchases in the suq were able to take their purchases home. It was common to see a number of unusual goods in the boots and back seats of the ubiquitous Peugeot 404s plying the streets. The second photograph is a detail of the first. The Central Police Station is on the left – all government buildings flew the national flag – the first road running across the end of the suq is now called Abdullah bin Jassim Street, and the Corniche is visible with the old port, or traditional craft jetty behind it.

These three photographs, again from March 1972, show details of the west side of suq wakf and were taken from the burj of the central masjid. The first gives a good idea of the character of the buildings that formed this part of the suq with single storey structures on both sides of the pedestrian route that ran parallel, and west, of the road. The first photograph shows the beginnings of taller development as a mezzanine level had been constructed within the building on the left, for storage.

The second photograph illustrates the two-storey development that was directly adjacent to and left of the buildings in the first photograph. It is difficult to know what was intended but the second floor contained both storage as well as, in some places, accommodation for expatriate staff operating the shops and providing an additional degree of protection to the goods in addition to those formally employed for that purpose.

These next two photographs, taken on an afternoon in August 1972, show a little more of the character of the shops that fronted the main road through the suq. The shops each had double folding wooden shutters to secure them and, generally, they were not enclosed or air-conditioned, improvements that slowly moved in during the 1970s. Note the relative lack of signs as advertising was not yet thought to be necessary, although later it became customary to add a sign with the owner’s name and his commercial registry number, usually given as ‘General Merchant and Contractor’.

The second photograph gives an indication of the numbers and type of people shopping in the late afternoon in summer. Most noticeable is the wide pavement. You can see that there is a large concrete addition on the outside of the pavement, this being the cover to the large drainage system that was taken along the wadi and through the suq to disgorge to the sea beside the traditional dhow harbour to the north of the suq.

Turning and looking south, from more or less the same standpoint as that used in the photograph above, this was the view in February 1974 and shows the building that can be seen in the old photograph above. The corner of the Bismillah restaurant can be seen on the junction just in front of it. The cars in the photograph are being diverted to the left to avoid the excavation works being carried out to repair the drainage system at the junction.

Round the corner, right, from this part of the suq was the central maqbara or graveyard. Opposite to it was that part of the suq that sold gold and jewellery and, further north, an area of workshops. These two photographs, both taken in April 1972, show the typical organisation of the shops and workshops in this part of the suq, with heavy double-fold doors secured by padlocks when the owner was absent. This particular part of the suq appeared to fabricate items to order as well as having a small supply of items relating to cooking outdoors for sale. This was also the area that sold large items such as suitcases and trunks, particularly metal. The lower photograph shows that the workshop appears to have specialised in kerosene lamps. The wall of the maqbara can be seen in the distance, the intervening land being used as a car park. This area, including the maqbara, is now all taken by car parking. The lowest of these three photographs shows the south-east corner of the maqbara viewed from the main road running through the suq. The covered suq starts on the right of the photograph, the Turkish fort hidden by the buildings on the left and, at the end of those buildings was the Arab Bank roundabout with the jewellery shop of al-Fardan.

North of the area in the photo above, and to the west of suq Waqf was the chief area in which the merchant families established their presence along Doha’s old littoral. This helped them supervise the movement of goods directly from the boats standing out in the bay, the smaller craft shuttling between them and the shore. This enabled many of the merchants to build their residences in this area, these buildings also incorporating storage for their goods. The Darwish, al-Mana and other merchant families developed in this area of Doha and I believe that the two buildings shown here were located on the western edge of the central commercial area and belonged to two of these families, though I can’t recall which. The image, made in 1972 shows that the building was suffering structurally at that time. I don’t know when it would have been brought down.

The first building, illustrated above, has an impressive scale, both in height as well as in the length of its walls, the building being essentially two storey with a room on the second floor roof and a badgheer improving ventilation to those using the room as well as the roof. By contrast, the lower building is smaller, being single storey but with two rooms added at first floor level – with the proportions of five to three bays on plan – and probably used in conjunction with each other. Many of these buildings started with their rooms being used by the owning families, but the upper stories being eventually given over to storage of goods. I don’t know the date of this photograph but would guess it to be contemporaneous with that above. Note that the buildings illustrate two different styles of local architecture demonstrated both in their massing as well as their vocabulary.