a collection of notes on areas of personal interest

- Introduction

- Arabic / Islamic design

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 01

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 02

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 03

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 04

- Islamic architecture

- Islamic urban design 01

- Islamic urban design 02

- Islamic urban design 03

- Islamic urban design 04

- Islamic urban design 05

- Arabic / Islamic gardens

- Gulf architecture 01

- Gulf architecture 02

- Gulf architecture 03

- Gulf architecture 04

- Gulf architecture 05

- Gulf architecture 06

- Gulf architecture 07

- Gulf architecture 08

- Infrastructure development

- The building industry

- Environmental control

- Perception

- The household on its lot

- A new approach – conceptual

- A new approach – principles

- A new approach – details

- Al Salata al jadida

- Public housing

- Expatriate housing study

- Apartment housing

- Pressures for change

- The State’s administration

- Society 01

- Society 02

- Society 03

- Society 04

- Society 05

- Society 06

- History of the peninsula

- Geography

- Planning 01

- Planning 02

- Population

- Traditional boats

- Boat types

- Old Qatar 01

- Old Qatar 02

- Security

- Protection

- Design brief

- Design elements

- Building regulations

- Glossary

- Glossary addendum

- References

- References addendum

- Links to other sites

Work

It is instructive to look at the Government figures relating to the workforce in Qatar in order to obtain something of an understanding of the predominance of expatriate workers there are in the country. But a distinction has to be made about the economic realities requiring the importation of significant numbers of workers in the construction and service sectors of the economy, and attitudes to working within the national community where there are significant cultural differences due to a number of historical factors.

In terms of a job, work is an ambition of most Qataris, though this conflicts with traditional attitudes of the badu. An aversion to work has been commented on by authorities in Oman, Bahrein and Kuwait and is considered to be a serious obstacle to the integration of nationals into a modern State. There are two reasons normally given by those who wish to work. Firstly, and in this order,

- they believe they are assisting the State in its development and repaying the Ruler for his help in improving their lot and,

- secondly, they must obtain the means to provide for their family.

Usually, this meant obtaining a job with the Government as there was little commercial activity in Qatar, and insufficient opportunity for an ordinary Qatari – unless he or his family were independently wealthy – to obtain the necessary funding with which to obtain on the open market a plot of land upon which to build a house. Although there is significant commercial activity now, there is still a problem buying land as it has dramatically increased in price.

In the West it is a commonplace attitude that the Arabs of the Gulf are rich. Both Westerners and northern Arabs believe this and it has been at the heart of much of the dislike felt by both groups towards Gulf Arabs. The reasons are essentially historical but many commentators have noted the continuing trends and mechanisms that perpetuate this unhelpful attitude. The invasion of Kuwait by Iraq was argued to be partly a consequence of the refusal of Kuwait to support its Arab shaqiqa to the extent to which the latter would like to be come accustomed.

Gulf Arabs have always been aware of the jealousies within these areas, and the extent to which they are disliked because of their wealth. In a political sense, budgets are found to assist poorer Muslim and other States but, in a personal sense there is a keen but hidden antipathy towards the more aggressive Arab States and the dangers they represent. In their awareness of this, some members of the Kuwaiti ruling family stated that they would institute a more egalitarian or democratic State when they returned to their country. This they are moving towards, as is Qatar following a series of novel initiatives made by the Ruler, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa and his wife, Sheikha Mosa.

This issue is also associated with the arguments for a more visible female profile in the society, and it is possible that these attitudes are now moving out from Qatar to encompass and encourage other nationals of the Gulf States. In this it might be thought that political and ameliorative policies are amalgamating at the expense of those Islamic ideologies discussed elsewhere. It is difficult to guess how progress will be made, and its extent. Women did not win any seats in the Kuwaiti elections of mid-2006, though the elections did see reformists making strong gains.

In the nineteen eighties and nineties there were, in Qatar, a number of financial problems associated with the inherent stability of the United States Dollar and its value in relation to other currencies, and the price of oil. The effect of this was that Government attempted to restrict the spending of funds. In turn, this created a situation in where there was little productive work. This applied to both the public and private sectors, particularly the latter which is heavily dependent upon Government for its funding.

Because of the lack of productive work there was a tendency for staff to have a casual attitude to the responsibilities for which they were paid, and this was reinforced by the lack of training towards work as a function of society. It was not thought to be necessary to work full time in order to carry out one’s job.

An important and complicating factor has been the understandable policy of expatriates to try to ensure they remain in work, and that their compatriots also do. To this end it is possible to identify a number of policies enacted by expatriates to relieve Qataris of the burden of their work. All is carried out in the spirit of genuine assistance and may – and often does – result in the expatriate working harder; but the result is the same: the Qatari will have less to do, the work will be carried out and everybody is relatively happy.

Times have now changed as there is certainly considerable work around. Many Qataris have left public service in order to take their position in family firms or to start business themselves. Some still work in the public sector but operate businesses through managers. This requires them to operate both public service and private work coevally, a balancing act which, when observed, seems to work quite naturally, but tends to frustrate expatriate businessmen who are unable to understand and work within the system.

Some nationals, as a matter of course, will often tell you how hard they are working, but this more usually supports the argument that they are not, and that they are aware of it. Having said that, it is possible to observe them working hard but not in a manner familiar to Western professionals. Those nationals who have studied abroad are particularly aware of this, but it is possible that the system in education where students have everything provided for them – which would not be the case in the West – also is harming younger Qataris. There appears to be a serious problem with young men not being able to develop responsibilities in the professionally related activities that can be argued to begin at the level of their tertiary education.

Arguments have been made to encourage young Qataris to obtain not just university degrees but professional associations in the West. To some extent this has worked in the medical profession, but not really elsewhere. It was suggested, for instance, that all nationals obtaining a professional degree should then work in a related office or offices abroad with a view to both learning the practicalities of office work as well as obtaining a foreign professional qualification. It was seen that there would have been a bonus in forging relationships with those professional offices.

The reason for this not working is that nationals can’t really afford to spend time out of their country, away from their families and the fast pace of development within Qatar. To a large extent this reflects the way the majlis works, the mainly informal system by which intelligence is passed within the community. The work model, then, is very different from that obtaining generally in the West, though it not perceived as such either by nationals or expatriates.

Westerners are generally unable to perceive evidence of a work ethic with which they are familiar; where productive effort is seen to be good in its own right or necessary for self development – the traditional Christian work ethic. They are not used to loose time keeping, meetings being dropped, people bursting in on meetings, more than one meeting being held at the same time, being introduced to strangers and having no idea of their status and relationships, promises being made and apparently being reneged on and, nowadays, the continual use of one, two or three mobiles interrupting the flow of conversation and business. There are many other complaints I have heard, but this latter is interesting as it reflects so well the manner in which the earlier mentioned majlis system operates.

In the early days of the State’s development telephones were an important element in facilitating the exchange of information so necessary to running private and public affairs. Meetings were interrupted by calls coming in and being made and most nationals had a large number of telephones ranged across their desks that were constantly in use. There was quite an important hierarchy for this arrangement which I have mentioned elsewhere. But now the mobile has taken over from telephones, not just as it has in the West, but to a far greater extent. The accompanying photograph, taken from a local newspaper in August 2008, notes penetration of the mobile market of 150%.

The foregoing may seem to be a detail but the note is there to illustrate one of the mechanisms illustrating how both work and personal affairs have developed. Mobiles may appear to disrupt meetings more than was the case with fixed telephones or the apparent lack of privacy, but it is just a development of the traditional manner in which society operates. Its significance is that it is now possible to speak to people all the time, wherever you are, and this opportunity is taken to an extent more than in the West.

Whatever the mechanisms for work, and the degree to which it is effective in Western terms, there is a very strong attitude among nationals who feel that they should repay the State and attempt to assist its development. There is a level of loyalty to the State that has disappeared from many other countries and that most Westerners may find unusual if not a little uncomfortable when they first experience it in Qatar. This is similar to the loyalty that is felt towards family and qabila and, in that sense, is an extension of that loyalty.

Because of this feeling, many nationals genuinely wish to benefit the State and are happy to work for the public service, but the mechanism they use to progress their service is to combine it with private business as there, too, they have a loyalty impelling them to support their family in both the specific and wider sense.

But management is still learning its skills within the State and many who work either do not have the goals properly defined for them, are unable to define goals themselves, or are rendered ineffective by the lack of integrated back-up. Management studies have been organised at the top of middle management level for Qataris only, but it appears to be having little practical effect. One of the reasons for this could be due to the fact that managers still require loyalty to themselves above loyalty to the organisation, and this is often the manner in which staff are selected and placed in their jobs within Government as well as within private commercial organisations. Loyalty to an individual conflicts with the need for an organisation to operate as a professional system, and this stems from the traditional way in which business has been carried out in the region.

It can also be argued that government, in facilitating placement of Qataris in the workplace by their additional support – such as the provision of drivers to take them to work, pay and holiday differentials, relaxation of supervision, and so on – establish a hierarchical system at odds with the requirements of efficient and effective commercial and administrative organisations.

The lower levels of management are almost exclusively the preserve of non-Qataris who maintain the records and correspondence and carry out all the necessary traditional support tasks. Although some new systems are being introduced, there are three essential difficulties:

- generally the skills being used are those learned under systems developed from, or directed by, colonial administrations and which, in many cases, continue unchanged,

- where new systems are introduced there is minimal skills development with existing staff, and

- as has been mentioned above, many of the expatriates have a direct interest in ensuring their continuing role within the country regardless of the efficiency of their own operations.

Taking this natural resistance into account, new management skills and techniques are proving difficult to introduce into Government departments. There is little in the way of change management operating to alleviate this resistance to the development of efficient organisations, and new systems, while appearing to improve management, are neither developing well nor integrating with those of other organisations. In fact, this is also applicable to the organisations themselves.

A complicating factor is that very few graduates seem to want to work within their field of expertise but seek other areas which, when they are rebuffed, tend to make them unhappy in their directed field. For the better students who are able to gain academic places abroad this is perhaps due to their being required by the Ministry of Education to stay within the initially selected field of study despite an increasing awareness of the wider fields available to students in the West. For the students who graduate from Qatar University it is perhaps due to the limited variety of disciplines available to them and the lower standard of the course compared with, particularly, the American courses from which the majority of Qataris permitted to study abroad graduated.

As the University is relatively new, being founded in the early nineteen eighties, it is perhaps not surprising that there is a disbalance between the output of the secondary schools and the requirements of government where the majority of Qataris will be found a place.

It seems to be evident that the work force is generally not crafted to suit the tasks it has to perform, and that the tasks themselves are ill-defined and unbalanced with poorly expressed and imprecise objectives and goals.

This problem is not restricted to Qatar but has been commented on in other Gulf States as well as in Saudi Arabia. In the latter country, blame has been attached to a combination of the failings of the educational system and an over-dependence on a foreign workforce. Although there is change, it is slow and it comes at the expense of growing impatience in the young.

Achievement is not measured in terms of accomplished objectives or goals. It is ambiguous and appears to be related to lack of perspective within all organisations as well as to the failure of the educational process to deal with the concepts of work, job satisfaction and progress. It is sad to note the numbers of Qataris who do not understand, or carry out satisfactorily, their jobs and who are unhappy at work. Achievement is more accurately related to the individual’s placement in society, and this depends in many respects on the operation of the socio-political workings embodied in the qabila system.

Women in the workplace

Increasingly, change is being introduced to the workforce market. Qatari women are now working in the private sector as well as for government, and not just in offices where they might not be seen, but in front line positions. Traditionally women were to be found in the Ministries of Labour and Social Affairs, Education, the Interior and Health, but they are now to be seen more openly, working in areas such as Immigration and other departments where there is a need to meet the public. For instance, government departments now have booths within shopping malls where female employees are available to meet householders who are unable to visit government departments during normal hours. While making a small beginning to resolve the problem of the disbalance between nationals and expatriates, the increasing exposure of women has introduced or exacerbated a number of other problems.

The issues relating to the education of women are some of the most significant in the Muslim world. These are religious and socio-political in nature, and their potential as agents for change is recognised as such both by those not wishing to see women move out of their traditional roles as well as those who want to see change. Much of the reason for this seems to originate from Islamic initiatives within the Western world where a degree of emancipation is thought to be a prerogative for developing a modern society. But there has also been a tradition in, generally, northern Arab states for women to take a similar role to men. But there has been, and continues to be, resistance.

In addition to religious rationale, colonialism is thought to be one of the reasons that women were not educated as were men due to the colonising powers having no interest in moving women out of illiteracy, this replicating, but to a greater extent, attitudes in their own countries. The nineteenth century witnessed education of women in some of the northern Arab states, but not in the Gulf until the latter part of the twentieth century.

While many see the increasing visibility of women in public as reflecting changing moraes, there are those who believe that there is less progress to gender inequality in this part of the Arab world than is being made elsewhere. Religion and education may be forces for change but some suggest that it is oil and its development behind an inequality of gender balance and the increasing stresses this creates within society. This argument suggests that women being unable to access the labour market results in higher fertility rates, poorer education and a diminished influence within the family. This, in turn, leads to a lessened ability to exchange information, develop political focus and gain representation in government; all these being areas where political and social emancipation is developed – outside the home. However, this appears not to be the case in Qatar where the initiatives resulting from the improved access to education for women appears to be having the opposite effect.

A look at the programmes of the University, the guest lecturers, the conferences, the exhibitions and the stated goals is interesting. It is in education and the importation of teaching staff and their programmes, particularly in tertiary education, that the initiatives relating to changing society can best be identified. These appear to mirror programmes in the Western world while making little allowance for cultural change.

The education of women to tertiary standards is a policy that is being directed from the highest levels. H.H. Sheikha Moza, has stated the goal to be:

…educating the whole nation. It’s upgrading…the education system, social system and political system. It is bringing a different environment, a different culture, to this nation.

It is not difficult to appreciate how ambitious this is, and how it might seem to other Gulf states. In fact she goes on to say that

Geographical lines and borders, they have no power at all. Not any more at least. They just reflect the sovereignty of the states. But I don’t think that there is sovereignty over people’s minds. What’s happening here in Qatar could affect the rest of the region. This is a possibility we shouldn’t deny.

Referring to Qatari women she goes on to state:

I hope that these changes will affect them in very positive way. [They] have potential. In the proper environment, they can reach their full potential. And this is what we are trying to do here. We are trying to create the right environment, because we don’t believe [Qatari women] are any less than anyone else in the world.

In many ways Qatar is in the vanguard of the Gulf, an issue which is receiving mixed comments as it promises to disturb many of the socio-political moraes of the region. The university system has expanded dramatically and caters for a large proportion of the women in the country. This has created a socio-cultural phenomenon which did not exist a generation ago; the university has become a social entity, a form of separate ecosystem. I shall make notes about this elsewhere but its relevance here is in establishing expectations.

Curiously to casual observers, the proportion of women entering tertiary education is greater than men in Qatar – 57%, in fact, and this proportion is similar in Bahrein and Kuwait. The reason appears to be twofold. Firstly, it is easier for men to move abroad to study, both practically and with the provision of a government grant. Secondly, and conversely, there are practical socio-cultural difficulties for women moving abroad to study as well as family pressures attempting to have them remain in Qatar and marry.

The point of this, and with relevance to the workforce, the university system is producing a cadre of well-educated, confident young women who are competent, believe in themselves and, in many cases, wish to take their place in the workplace. The difficulty is that there are not the opportunities that many of them would like due to a combination of the traditional practice of separation of the sexes, and the matching of education to employment opportunities. In addition there continues to be resistance within some families to women working or, perhaps more accurately, for them working in certain areas or positions. Just as important are the conflicts arising in the hierarchical placement with regard to men.

In addition, the focus on tertiary education – for both men and women – has meant that vocational and technical education initiatives have not progressed. This exacerbates the problems of opportunities for women in the workplace.

Traditionally, women have seen their most likely employment in areas within the field of medicine, particularly gynaecology, pharmacology and dentistry, along with education where there is an obvious need for female teachers, the law and the arts though acting has been traditionally frowned upon. The media generally are likely to attract women to them, and the fact that Qatar is the home of Al Jazeera, makes this field more attractive to them. Areas such as science and engineering are still very much the preserve of men as they are in the West.

Increasing emancipation sees more women in public wearing, for the most part, the hijab. The various uniforms worn by women in the workplace use a form of this for head covering, usually matched in colour with the rest of the dress.

The increased incidence of women in the workplace has meant the employing of additional transport. Qatari women tend to be taken to and from work by a chauffeur, very few of them using the small buses operated by some organisations. This has brought about additional traffic loading of the road system, contributing to the problems that are experienced every day by nationals and expatriates alike. However, with the advent of mobile ’phones, the irritation of long journeys can, to some extent, be ameliorated.

more to be written…

Expatriates

The majority of the population are expatriates who have come to work in Qatar in increasing numbers since the nineteen thirties. The majority of them appear to be non-Arab speaking foreigners but, due to the location of the peninsula, a number of them came from the Arabian hinterland or farther, and some have even become nationalised, though this is not easy to achieve as issues relating to nationality are significant, and discussed a little further here. However, it is true to say that many, if not the majority, are not natural Arab speakers and are in Qatar out of economic necessity. Within Qatar they have formed communities and alliances and, as far as they are able, they continue the habits and practices of their natural communities. They are employed in all areas of the economy, particularly those of management, the professions and, perhaps in the greatest number, labour.

Many come to the Gulf to work, but it is not always the easy life they might have assumed before coming. Perhaps that is an exaggeration as not all believe it to be an easy way of making a living. For many the Gulf represents one of the few places where a job can be readily found, but where they find the work can be extremely onerous. For many of them, it is either that or nothing, and this attraction is what draws a lot of people, particularly from the Indian sub-continent where there is an active infrastructure locating and encouraging workers to move abroad for the benefits they might bring to their families – and the middlemen, of course.

If the main reason to come to the Gulf is to make money – perhaps in different proportions, to repatriate the funds in order to feed families at home, provide for a pension and to enjoy a better life style – then many are disappointed. It is not always easy to live comfortably as there can be more elements affecting life for expatriates than there are likely to be in their home countries, and which they are unable to control or in which they may have their say. But where they have prior knowledge and have been able to make an informed decision, it is still a method of benefitting their family at home.

Many, if not the majority of the expatriates who come to join the workforce in Qatar come as groups or are related either by family or geography to others in the group or to the groups they will be joining. In fact, many of the middlemen who provide expatriate labour, find them within towns and villages in their home country and arrange for them to be brought to Qatar in recognisable groups. There are often middlemen involved both in Qatar and in the foreign countries. Not only does this system facilitate searches for workers, it empowers and to some extent eases their transition into a foreign working environment.

Although this is largely no longer the case, these groups of workers used to come into the country and be housed in the abandoned buildings of Doha’s inner ring. Nowadays, much of the accommodation is provided in the form of new-build constructions which do not have the character or many of the benefits of the older housing – particularly the courtyard houses, an example of which is shown here. It is interesting to see how the Pakistanis living here have decorated and equipped their home with a water cooler and refrigerator on the right, small national flags to remind them of home, and significant geometric patterns, a vase with flowers, printed phrases from the Holy Quran and a written exclamation for awe – maa shaa’ allah. Around the courtyard are a collection of unmatched furniture enabling them to sit companionably when not working. There are more images of this type of housing on the page looking at external majaalis.

These expatriate groups would employ one or two of their group to provide tailoring and cooking for the whole group. Familiar cuisine and the ability to turn out well on Fridays are certainly two of the prerequisites that should keep workers happy. In this photograph a group of expatriates sit and stand comfortably on a roof inside the inner ring of Doha while, on the left, one of the men appears to be having his hair cut. This will be a group working together during the day and deriving a degree of relaxation from their shared and common bonds which, to some extent, will take their minds off their need to be in a foreign country in order to make the money to support their families at home.

With the expatriates come many of their socio-cultural habits which may seem strange at first glance. It was noticeable in the 1970s that many of the Pathans who obtained bicycles decorated them in a similar manner to vehicles in their home country. These two photographs, taken from a number made in the early nineteen-seventies, show two different approaches to the use of mirrors. In the first the mirrors have been used to frame photographs of female Hindi film stars. Plastic flowers, tassels, a decorated seat, frame and mudguard add to the customising to create a very individual bicycle. In the lower photograph, there are certainly mirrors which I had thought on first sight to be more than necessary for all-round viewing but, on closer inspection found them all to reflect the rider. On other bicycles I have seen a combination of film stars and mirrors, again the latter reflecting the rider.

The ability to live together in national groups is an obvious benefit to expatriate workers. There is a degree of comfort and support which helps these workers adjust to the pressures of living in a foreign country. But it is not easy. It used to be possible to see how many of the groups showed allegiance not just to their own countries, but also to Qatar with the display of flags in the form of the Qatar flag, but green instead of maroon.

Generally this section of the notes refers to manual labour, but times have changed and there are significantly larger numbers of expatriates in Qatar now, and in all classes. Management and professional classes are heavily expatriate, and each creates their own socio-cultural grouping replicating in many of their aspects, their home environments. This produces a number of facilities which were originally alien to the peninsula but which have become fixtures there using customised spaces and schedules for their enjoyment. Some of these have been adopted by nationals, but in many aspects there are difficulties created by these imported activities, many of them conflicting with the traditions and customs of the peninsula.

more to be written…

But inflation is a problem all over the world. It affects expatriates disproportionately as they are usually tied to relatively short fixed term contracts and have little or no negotiating power. This is certainly true for labourers but is also true for other groups. This headline might obtain at any time but in August 2008, the rising cost of living in Qatar saw the newspaper article illustrated here. The article stated that the average monthly expenditure of an expatriate family has gone up by over 46% to Qrs.13,329 between 2001 and 2007. The proportion of this relating to housing had risen over that period from 21% of that sum to 30.8%. I have to admit that averaging figures for expatriates is an extremely tenuous exercise as they do not form a similar profile to the nationals in terms of age and sex distribution, but it is interesting figure nevertheless.

more to be written…

Pressures

There are many pressures on expatriates. Some are obvious and would be known before they move to the Gulf, some found only after arrival, and others of which they might never be aware. The majority of people who travel to the Gulf do so with the intent of working. There is, at present, a relatively small number of tourists but they have little to do with other expatriates other than if they are brought out by relations, or those they come into contact with as part of the tourism system. It is unlikely that they feel any of the pressures of the expatriates living and working in the Gulf; but articles such as this contrast certain aspects of the socio-cultural environment for tourists with their experiences in other countries.

The first issue to note is the extent to which expatriate communities have their own socio-cultural systems to help and protect themselves in a variety of ways. These range from the briefing, exchange of information and assistance to the more psychological needs of those living outside their comfort zones.

One of the greatest problems perceived by expatriates is their unequal status compared with nationals. This is an issue all over the world, often considered to operate against nationals’ interests but, in the Gulf, definitely thought by expatriates to operate against them on a number of different levels. For instance, the announcement of fines for wasting water has raised a number of comments, essentially complaining that it would affect only expatriates as the Kahramaa inspectors, who are expatriates, will not risk their jobs by attempting to impose fines on nationals. Whether that is true or not, that is the perception: and perception tends to be more dominant in the mind than fact.

Behaviour of expatriates

A general understanding exists within the different expatriate communities that there should be no misbehaviour in Qatar. Due to the manner of their employment and their need to earn funds to send home, most expatriates will try to behave in accordance with the requirements not only of their national and employment community, but also within the state’s laws and practices.

Companies have strict rules governing the behaviour of their staff, some maintaining their own security officers to enforce this. Embassies issue suggestions about behaviour in general, perhaps concentrating on behaviour in public, but usually reminding their nationals of the possible penalties for infringement, while bearing in mind the consequences of individals’ behaviour on the status of their mission. But there is little or no policing by embassies of their nationals in Qatar, even though some would like to.

There is a common flouting of both laws and social codes by many expatriates, the latter a practice that can be readily observed almost anywhere in the country. There are certainly areas where ignorance creates problems, this being exacerbated when Qatari nationals have expectations that are different from the behaviours normal to expatriates in their various home countries. For instance, women’s dress is one such area where there is considered to be a lack of courtesy to the resident population. It is not unknown for nationals to make their feelings known openly and, certainly, it is discussed between nationals as an irritating issue.

However, there are other areas where there are habits or practices in the West that are not really understood, or which are now considered to be potentially dangerous to countries in the Arabian peninsula. Abu Dhabi, for instance has shown concern by arresting plane spotters recording the identification numbers of aircraft, and of an architect who was photographing buildings.

Plane and train spotting are well-known activities in the West, even if thought by some to be a mildly eccentric pastime. But the practice is a logical consequence for those who have developed a keen interest in the evolving design of aircraft and, perhaps, of the movements of aircraft around the world when it is felt necessary to record the flights’ registration numbers. Most airports in the West have people watching and recording planes and their movement in and out of the airport, some airports making provision for spotters.

Photography is now practised by many as everybody seems to carry mobile phones with a photographing capability. And social media sites such as Flickr have thousands of photographs of aircraft at or near Gulf airports.

It is also a feature of the Gulf states that their architectural structures are notable, some of them being in the forefront of architectural design. Again, thousands of photographs are taken of these new structures as a record of visits or as designs worthy of research and comment.

But it is not surprising that there should be concern by security authorities for the recording of buildings that they might believe to be at risk from terrorist attack. This is a subject that is widely written about with many experts believing that those who wish to focus on specific buildings or activities for criminal or terrorist purposes will do so, and will ensure they are not caught in the act. Unfortunately it is becoming more usual for photographers to be prevented from taking photographs openly in public as well as in private areas such as malls, ‘security’ being the answer given to those questioning the private guards.

Here there is an obvious conflict between the perceived needs of the security authorities and those promoting tourism. Each country wants to keep itself safe from attack, but at the same time is actively exploiting its new vision, encouraging people to visit and enjoy themselves. For those visiting these newly developed states there is an immediate wish to record their visits, and photography is the most immediate response, again witness social media.

more to be written on weather, exit visas, religion, cultural, moral, isolated communities, relationship between expatriates and tourists…

Tourists and tourism

The most marked impact on tourists and newcomers when they first arrive in Doha is said to be, firstly, the surprising extent and pace of the construction activities around, particularly, Doha and, secondly, the contrast between new development and the remaining or reconstructed physical past. Perhaps the most extreme example of the latter is the dramatic view of the new building developments in the New District of Doha, particularly at night, where the lights within and on the new buildings suggest an interesting focus for the area and an attraction to visitors.

However, this attraction contrasts with the lack of interest there is for tourists within the New District when compared with the activities tourists might anticipate and experience in areas of similar visual density, such as New York or Singapore. The feeling of visitors who investigate the New District is that it is one for show or display, there being restricted pedestrian access and few activities or foci of suitable interest other than the buildings themselves, particularly at night. In this photograph the buildings are seen as a attractive backdrop across the West Bay viewed from an area of touristic relaxation, perhaps inviting investigation.

Not only is tourism a difficult activity to direct and control, it is also one that is hard to define when seen as an element of, or adjunct to education and cultural activities. The state recognises this and notes the difficulties in modernising while preserving the country’s culture and Arab identity. As such it is an important strand in their view of the future, this being an important objective of the national vision for 2030.

References are made in a number of official documents to the need to produce and implement a strategy that

is an integrated effort to ensure the country’s sustainable development by reducing its reliance on its hydrocarbon resources, while also placing it on the world tourism map and helping promote and perpetuate its people’s culture, values, and traditions.

While the efforts to integrate a nascent tourism industry into a rapidly developing state are admirable, it is not easy as there are obvious areas of conflict between the requirements of the industry and with those of other agencies, as well as cultural and educational difficulties that militate against the assimilation of culture, values and traditions into the requirements of the tourist industry.

Tourists nowadays are selective in their choices of destination. While there are few places or events that are not accessible to the potential tourist, they compete in their areas of interest and, of course, cost with most people wanting to obtain value for their holiday. Qatar’s tourism website suggests, in its ‘things to do’ list that

you can play world-class golf, cycle along hundreds of miles of desert off-road, take road-trips to beaches, hunt for fossils or get lost in the moment of a brilliantly crafted scene of desert dunes at the inland Sea

and specifically promotes the Museum of Islamic Art, Katara Cultural Village, Fort Zubara and desert camping and dune bashing. Whether the latter is consistent with the stated intent of safeguarding the environment may be debatable, and other countries have very similar opportunities for tourists. The United Arab Emirates, for instance, vies with Qatar in the activities available to tourists.

But the needs of tourists are also debatable, many requiring only a small degree of authenticity while demanding access to the more familiar aspects of Western taste and culture. In this way, the authentic experience can be substantially diminished such as it is argued to be in suq Waqf. While the re-built suq has an architectural similarity to the original that preceded it, the activities are different. There are now a significant number of commercial additions – restaurants, art galleries, gift shops and the like – that did not exist in the original suq and create a different, more sanitised feel. For instance, shops that sold traditional fragrances now also must sell modern perfumes, while artefacts are now produced specifically to cater for the tourist market. Contrasting with the ‘authentic’ suq are the glimpses seen immediately adjacent to it of the new constructions of the state, significantly different in concept, scale, material, character and detailing from traditional architecture of the peninsula.

New developments – and of these there are a number – use pastiche and a foreign design vocabulary to induce in both the tourist and the expatriate workforce, an international flavour to their surroundings, suggesting a degree of safety in this familiarity. For instance, a quasi-Italian vocabulary is notable in many of the residential and commercial developments. But, as is argued elsewhere, this does not promote a feeling of safety within a Qatari or even Arab culture, but in an Italian culture. Moreover, it is illusory. Not only does it alter the physical framework, it diminishes something of the cultural framework within which Qataris live and work, taking from them a significant element of their heritage.

Tourists, and those who travel, are increasingly presented with comfortable, artificial environments promoting safety and security while presenting the bored traveller with retail opportunities. These settings, in accordance with Koolhaas’ views on airports, have an international feel to them while being transient in essence, surrogates for the city where both tourists and locals may wander at will, though not all being able to afford to buy.

more to be written…

Servants

There is an important distinction to be made here for Western readers in understanding what are meant by the term ‘servants’. Further down the page I use the term more in its accepted Western sense, but elsewhere on this and other pages I have written about the way in which families live together and share household duties, some of those members of the family perhaps having more of a service role to an outside observer. The family should be understood to include others who may not be related, who may share this role, but are considered an integral part of the family.

This may be true also of those brought up with the children of the household. These might include some who are brought into the household either as children of people who are servants of the house, or of widows with their dependents, in effect forming a service relationship but, within the wider context of the family, being an intrinsic part of it. Where these children are male, they will enjoy most if not all of the benefits of being a part of the family and, in the higher areas of the society, they will be treated in much the same way as if they were the children and, later, the adults they live with.

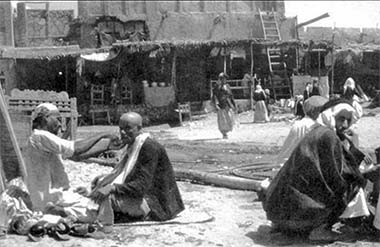

There are a number of memories I have that typify the concept of servants and the relationships to be found within families, particularly the larger families. This photograph is typical of one of the common sights I can recall: three men sit comfortably outside the entrance gate to a compound, passing the time of day. One of them is a Qatari, the other two perhaps gardeners, cooks, gate-keepers or guards. In essence it doesn’t matter really what they are, but what they represent, and that is a group who have a relationship with the compound and the people who live in it, and those who visit as guests. In a sense you are looking at a majlis, albeit in an informal and small form, but that is how information was traditionally passed and, of course, still is. Interestingly, behind them can be glimpsed the end of a dikka complete with rug covering, which might be considered to represent the next step up in the majlis chain.

What I have written above is a relatively simplistic view of the family and its servants. I shall attempt to write more on the complexity of these relationships later.

more to be written…

Many Qatari families have had and, increasingly, have servants to help in the running of their households. The reason is that servants are affordable due to the number of men and women seeking work in the Gulf from the Indian sub-continent and other regions to the east of the Gulf. From time to time there is a change in fashion as another country is discovered to have people who are willing to work in the Gulf and possess qualities that commend them. One of the latest has been the import of Nepalese. Honesty, diligence and a modicum of skill are the basic requirements, but the ability to speak Arabic or English is also necessary depending upon what the intended work is. It should also be understood that many expatriate families employ servants.

The selection of expatriates to work in the private sector tends to be based on whether they are to help within the house or only outside. Those working inside nowadays tend to be from India and the Philippines, those outside from Pakistan and Afghanistan where they work as gardeners, gate keepers and drivers. Those inside are mostly women, those outside are always men. However, staff may also work in private offices as well as in the home. In these cases the selection seems to have much to do with the character, capabilities and versatility of the individual. In some cases, such as gardeners, these are shared between a number of households, some of the gardeners also having jobs with government agencies and working in their spare time within the private sector.

Families have always worked together at the various tasks necessary for the smooth running of their households. The extended family has been, in this respect, a natural working unit, all members helping in its business. But, in the past, slaves were brought into the Gulf from Africa where there was nobody capable within the family to carry out that work, or to carry out work that was either difficult or where there would be increased return from a larger workforce.

The increase in servants, while obviously assisting in the running of households, appears to have created a number of problems for Qataris. These difficulties arise not only from the training, education, skills, habits and attitudes of the servants to their work, but also from the attitude of Qataris to having the staff live with them.

There is rising concern within the Gulf that foreign labour should be reduced although, paradoxically, there appears to be a progressive requirement for servants to perform an ever-increasing variety of tasks in and about the house. In Oman, for instance, where the expatriate work force comprises only forty per cent of the total in 1989, the Sultan exhorted his people not to be ashamed to take on menial work in the service of their country as it denied them their roles and opportunities within their society, as well as perpetuating the need for foreign labour. It is difficult to see how this trend is to be reduced in the area of domestic service. In fact, overtly or covertly, there seem to be a number of good reasons why foreigners are preferred, and why this is often extended to a preference for non-Muslims and English speakers.

Non-Qataris can be paid low salaries that are, nevertheless, higher than those that might be obtained in their home countries and, consequently, attractive to them as well as employment agents both in Qatar and their home countries. Where domestic employees are non-Muslims they are not considered a threat to the household’s practice of Islam, and proselytising would be cause for immediate dismissal, or worse. Servants would be foolish to gossip or, if they do, it is likely to be only to their own nationalities, and unlikely to become current within Qatari society. An incidental consequence of this is that a considerable amount is known about the operations of Qataris within expatriate communities.

Domestic servants are also poorly paid, a government labour force sample survey states, revealing that their average pay is a tenth of that of a government worker and that, with no protection from labour laws, their working hours are not protected with their working, on average, fifty-seven hours a week.

Where servants speak English, or another popular language other than Arabic, they will be able to impart that language naturally to the children in their charge, and English is the lingua franca of the Indian sub-continent and nearby regions. An unfortunate consequence of this policy is that the English picked up by Qatari children usually has basic errors in terms of both accent and grammar, and that can’t be eradicated by later, formal teaching.

Many of the servants coming to Qatar are qualified in areas other than those for which they find work in Qatar, but economic circumstance requires that they move to fund their families living in their home countries. This in itself can cause difficulties with attitude to work and can be exacerbated by social contact with friends, relations or other nationals working in the country. Certainly the service population look for opportunities to meet their compatriots and this can cause difficulties between employee and employer. The comparatively low salaries together with delays in payment and poor living conditions combine to induce at first resentment and then an aggrieved attitude towards both employer and country. Additional methods of earning money are sought and this can lead to police action either due to the nature of the alternative method of earning, or to the employee breaking the terms of his or her work permit.

Attitudes to work vary but it is interesting to observe the manner in which servants perceive and carry out their work. Employees seem to have an overwhelming desire to ensure that they are irreplaceable. This tends to be demonstrated particularly in spoiling children, specifically the boys of the household who are treated as being more important than the girls, regardless of age. Constant cosseting, a lot of physical contact, the use of sweets and soft drinks as reward and comfort, make the job of the mother far more difficult, and the child more spoilt. Conversely it makes the servants’ job no safer as they are often treated badly by the children with no recourse to the parents for intercession.

This relationship between servants and children is also notable in that it rarely seems natural for the reasons described earlier, though I admit this might be due in part to my own preconceptions. The relationship follows the pattern of traditional family life when members of the family who had been divorced, or were poor or in other ways needed assistance, became an accepted part of the family. This would also include, in the past, the use of slaves where they, too, become in many ways otherwise indistinguishable elements of the family.

The servants who take on the responsibility of looking after the children have different relationships with them depending on the age of the children. It is nearly always female servants who look after children of both sexes, and this relationship continues with boys until the age of about seven or eight and with girls a little later though it is extremely difficult to put a rule to the practice as it differs from family to family, maturity of the children and their relationship with their parents. With boys I have suggested an age when there is an increasing strong relationship between a boy and his father, with the boy being gradually introduced into men’s society and with his understanding of his role as a man becoming more palpable in his relationships with the members of his family, particularly with his sisters.

In the past, when houses contained just rooms with no notional function servants, like the family, slept wherever circumstance required. Nowadays servants tend to have a room of their own but will often sleep in the bedrooms of the children in their care, or even in the corridor outside. Whether this is an economic necessity, a practice arising from the servants’ need to feel safe in their job, a concern for the children in her charge or requirements of the employers, it is difficult to say; I suspect a bit of each.

This practice is even more marked when the family is travelling. Here, perhaps, it might be thought to be more of an economic imperative, but with disposable income not always being a factor, it is perhaps more of a true guardian’s role in safeguarding young children in a transient environment.

Many of the foreign domestic staff in Qatar are despondent, demonstrating their unhappiness in a number of ways, but the State will continue to attract foreign staff, particularly from south-east Asia and the Indian sub-continent, in order to cater for the various requirements of its nationals. Foreign governments, from time to time, attempt to embargo the use of their nationals as servants abroad, but this rarely lasts more than a few months as the need to maintain political and economic links with the better-off Gulf States continues to propel domestic servants into the Gulf. There is, however, an increasing level of intervention on behalf of nationals who have been mistreated, and at least one embassy attempts to insist on a minimum wage for domestic servants.

The attitudes of servants to rubbish and dirt are interesting. Perhaps due to the manner in which they were brought up they do not perceive these in the same way they are regarded in the West, and it is perhaps a paradox to see how clean the individual is in his daily laundered clothes operating in a less than clean environment. Cleanliness is not equated with hygiene. Thorough cleaning is required by houseowners but rarely effected, and never seems to be volunteered by employees. Dirt is moved out of the way but not taken up and moved off site. Dust is flicked off surfaces where it is visible and falls nearby. Commercial polishes are only used rarely and often are wrong for the job for which they are used. Hard surfaces are washed daily if possible and a lot of water is wasted in this manner.

I have written more on this below, under Serviced population.

Slavery

This has always been a delicate subject to discuss, whether in the Gulf or elsewhere. In Britain the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was passed by Parliament in 1807 and this was followed in 1833 by the Slavery Abolition Act which outlawed slavery in the British colonies. This created the impetus for the British to deal with slavery in the Gulf.

The nineteenth century saw the British nominally as guardians of the Gulf – though this was not a view universally held, even by the British who found that their attempts to stop the illegal trade were continually thwarted by more manoeuverable Arab dhow s and a combination of subterfuge and armed resistance. The trade had come about due to the need to feed the growing date and pearl markets in Europe and the United States, the slaves being brought from the east coast of Africa. But this had been declared illegal in treaties made with Gulf rulers in the mid-nineteenth century and the British were constrained to stop the practice. This proved to be virtually impossible due to two factors:

- firstly, the great demand and the consequent efforts made by slave traders to fulfill the requirements of the nascent industries and,

- secondly, the turbulent state of the British parliament combined with the different agencies involved in running this part of the British Empire – the Admiralty, Colonial and Indian Offices.

It’s perhaps also worth mentioning in the first case that the Gulf was not the only place where indecision and the lack of an informed British public allowed this practice to be perpetuated. Albeit a hundred years earlier, Moroccan pirates captured and enslaved thousands of Europeans and North Americans with the relevant governments doing little to stop the practice or free and return the slaves to their home countries.

In the Gulf slavery continued into the twentieth century, though not to the extent commonly believed in the West. Writing in the nineteenth century, Colonel Pelly had noted that there were only two industries in the Gulf, slaving and pearling and, in 1924, the British Resident in Bahrein wrote that there were still slaves being introduced to Qatar with a tax of eighty Rupees per head. In line with their policies, the British continued to resist the practice and manumitted slaves wherever possible. The difficulty with this was that there were few places where manumission could be effected, the nearest to Qatar being Bahrein. In certain cases slaves were manumitted by their owners but, chiefly, slaves had to escape in order to be able to obtain their freedom.

In Qatar the practice continued after the Second World War mainly as there was little done to suppress it. It has to be said that slavery was not particularly onerous in the Gulf by the twentieth century, there being a number of cases where slaves were manumitted but continued to live and work with their previous owner. Slaves were seen as part of the family and intermarriage was not uncommon. Certainly this was the case when seen by outsiders and, to a large extent, slaves shared the benefits and disbenefits of their families quite naturally. The last years of informal slavery can be seen to have been benign.

Talking with Qataris about this element of society can be difficult, but it is often what was not said that was interesting and informative. What is noticeable is that freed slaves can be seen in certain areas of society such as the security forces, music and dance, these latter two areas being discussed elsewhere.

Diving and pearls

Pearls have been at the heart of Qatar’s existence for centuries. It is difficult to underestimate their importance not just as a commodity, but as a driver and regulator of the lives of the people living in the peninsula. Its situation mid-way along the Gulf, and the wide distribution of pearling banks around its littoral, made Qatar an extremely important element of the Gulf pearl economy. This image is one of a number of photographs issued by the Ministry of Information in the 1970s publicising the State and its history.

Once the slave trade was forbidden and piracy stamped out, pearls became the chief industry of the peninsula, and the main source of its wealth or, rather, the wealth of its pearl merchants and their business partners. This seconds photograph shows pearls that have attached themselves to the shells in which they were found and, as such, are unusable. From the photograph below it is possible to see something of the range of colours in which they occur, but in this photograph the two pearls which have agglomerated can be seen to be distinctly different in colour.

The richest pearl banks were located off Ras Rakan, the north tip of the peninsula, so Qatari merchants were in a good position, literally, in order to be able to obtain significant value from this industry. It was crucial to those living on the peninsula and created a significant attraction and benefit to those settling there. This sketch illustrates the position of the main pearling banks. It is evident that Qatar’s long north and east shore line was close to a large number of the pearl banks compared with those north of the eastern Gulf Emirates.

Natural pearls are some of the most beautiful natural objects to be found. They have both a tactile as well as a visual quality to them. It is no surprise that those who won them appear to know every one that passes through their hands, together with the detailed story behind each. As such they were appreciated not just for their value, but for their individual character and beauty as well as their history, some of the merchants are reluctant to sell pearls that have significant meaning to them. In a sense a significant element of the history of the peninsula can be described in pearl collections such as these. In the lower photograph, taken from a film made in 1966, a group of merchants are looking through their collections, some of the pearls being held in sizing sieves similar to those in the upper photograph.

You can see in the pearls shown in the first photograph something of the range of colour and shape that characterise the pearls found in the Gulf around Qatar and the other Gulf States. Sadly for those associated with the trade, there was a severe downturn in Qatar’s pearl market around 1907, followed by the 1927 depression and the Japanese cultured pearl industry taking the market away from the Gulf in the 1930s, creating a more regular pearl, one which could be grown to order. You will see that a number of these pearls shown here are irregularly shaped and unsuited to stringing as a pearl necklace of matched, graded sizes and similar colouring. Known as baroque pearls, they still have considerable beauty with many preferring them to regular, matched pearls. The lower photograph shows a decidedly baroque pearl, still in its shell. I have seen Qatari dresses heavily covered in patterns of baroque pearls sewn onto them, and utilising a variety of shapes and coloured pearls.

This first photograph, taken in 1966, shows a pearling dhow with it oars shipped, the pearlers singing, one of the characteristic folkloric activities now being developed both to retain a record of this element of the peninsular history, but also to entertain visitors, guests and the like. Dancing and singing of pearling is a regular feature at many events, private and public. Like the sea shanties sung by sailors on traditional, sailed, ships rhythmic singing developed with the need for the crew to carry out activities together. Commonly this would relate to heaving anchors, setting sails and rowing, but it was also an activity the crew would use to relieve something of the tedium and hardship of pearling. Note in the lower photograph the number of crew – three or four – required to pull each of the heavy sweeps, an operation which is carried out standing. In the lower of these two photographs of crew at the sweeps, there appear to be only two men at each. Due to the height of the deck above water, and the fact that the sweeps are operated from the deck, the sweeps have to be operated at a considerable angle requiring those at the end of the sweep, where the moment against the masaanid al majdthaaf is greatest, to handle the sweep at quite a height.

This is one of a number of official government photographs published in the early 1970s both in a book and as postcards and, I believe, a film shown on television. It shows a pearl diver entering the sea to begin his search for pearl oysters on the sea bed. More commonly, the divers would stay resting in the water by the side of the dhow for a number of dives, dropping to the sea bed from there. The photograph, and those above, also give an indication of the numbers of crew customarily used for pearling dhows.

The crews consisted of divers and oarsmen, but there were also specialists, particularly cooks with animals being carried in order for the crew to be given fresh food to keep them healthy as well as giving them a change from fish. It was not always possible but, where it was, supplies were provided from the shore, and this would also apply to some items that might need providing or mending when this could not be carried out on board. These two photographs show a pair of goats eating on deck and, below them, the dhow–s cooking fire set in a metal tray in order to provide an element of safety, and with a coffee della being taken from it.

The diver would enter the water wearing a nose clip or fatam, and carrying a net basket attached by a line to the dhow. They use the basket to carry the oysters they find. When they have exhausted their breath they use the line to signal to the hauler on deck that they need to return and he will help their ascent, pulling them up and to the boat where the oysters will be collected and the diver return to the sea bed.

The life of a ghais or ghawwass was hard. Customarily he would spend the whole of the pearling season out at sea in order to maximise the number of pearls won from the pearling banks. There were three seasons for pearling, the main one, known as ghaus al-kabir beginning around the second week in May and lasting the whole of summer until around the third week of September when the date season begins. This main season was preceded by a ghaus al-barid which might last around forty days. The main season might be followed almost immediately by radda, a shorter season lasting around three weeks. The fourth season was winter when, rather than taking the boats out, pearls are won by wading in the shallow waters, a practice known as mujannah. Pearls won this way are not of the quality found further out at sea but had the advantage of being untaxed.

The boats remained out on the banks, and the divers worked from dawn to dusk, sometimes to considerable depths and making up to fifty dives a day. There might be a break in order to re-supply the boat or make repairs, but the need for this was dependent upon a number of factors, the owner and naakhuda preferring to keep the boats out to maximise their returns. There was also the possibility of a break in their time at sea if raiders approached their villages when a watchman would raise an alarm and the fleet would return to protect their animals and homes. Those in the villages would retreat to protective towers whose entrances were elevated some distance from the ground. To give some degree of protection against this and, more particularly, piracy, the British navy patrolled the Gulf during the pearling seasons.

The boats were captained and crewed by a variety of men from the littoral villages, the hinterland as well as from Persia, the Indian sub-continent and Africa. In addition to the naakhuda and the main crew of ghais and sa’ib there would also be a cook and, often, a drummer and singer, naham, employed to benefit the crew.

Here are a group of divers in the water, each wearing a fatam or nose clip, and apparently resting before making another dive. They will place the oysters they find in the small nets, or diyin, hung round their necks. The photograph also shows their guide ropes which will be held by a sa’ib on board their boat. It is likely the photograph was posed as divers did not descend together, but went at their own pace, holding their breaths for different times, two minutes being relatively normal.

The second photograph, taken from an official Department of Tourism poster of the 1980s, also posed and shows a diver resting on the surface with the fatam sealing his nose. The fatam was traditionally made from turtle shell or, more recently, from wood. Its particular characteristic is to have a degree of flexibility or spring to grip the nose without breaking.

A number of coir ropes are associated with each ghais who will have two associated with him when in the water. In addition each diver will have a zabeen which has a loop on it in which the diver places his foot as well as a stone weight, hasa, attached of around four to seven kilograms to help him drop to the sea bed. The diver’s partner, the sa’ib pulls this up when the diver has reached the sea bed. When the diver needs to move to the surface, either because he has filled his diyin or has reached the limit of his lung capacity, the sa’ib will bring his diver to the surface by pulling on the second rope or hadaa which is attached to the diver’s waist. The divers also wore ear plugs to assist with the problems of the pressure of the water at depth as well as khabt to protect their hands.

Once the divers brought up the oysters from the sea bed in their net baskets, the sa’ib would place them on deck where they would be left overnight in order to weaken the muscle structure holding them closed. The crew of the boat would set about opening them in the morning using their knives, and removing any pearls found under the supervision of the naakhuda, the master in command of the pearling craft. In addition to finding and saving the pearls, any particularly good examples of mother-of-pearl – the nacre lining – would also be saved for decorative work.

These two photographs were both produced by the Ministry of Information and published in a variety of other forms as well as, later, online. They illustrate something of the conditions on deck with the men working in groups and the discarded shells put aside for later dumping back into the sea.

The naakhuda was the individual responsible to the owner for the pearling operation of his craft and was selected on the basis of his experience, knowledge of the pearling beds together with his maritime skills. As master of the boat he was also responsible for selection of the crew and their behaviour during the season, putting him in a position of considerable power and responsibility. Traditionally he would sit at the stern of the craft in order to be able to keep an eye on all the activities on and off it.

When pearling in the Gulf was controlled by Persians in the eighteenth century, the oyster shells were taken ashore unopened, the opening being subsequently carried out the under supervision of a Persian officer. Generally the opening of oysters was considered to be a matter of trust and theft a matter of shame, not just for the individual but also his kinsmen and tribe.

As master of the pearling boat the naakhuda was also responsible not only for the winning of pearls, but also for ensuring that the crew were able to operate for the period of time they would be at sea. This required that the crew had sufficient provisions for their time at sea and he, or more usually, merchants would make loans to the crew as advances against the eventual sale of the pearls. Because of this the success or failure of the pearling season had an immediate effect on the people of the Gulf. This applied not only to those winning the pearls and their families but also those relying on their value – the government who took taxes and the merchants who traded in the pearls as well as those supplying goods.

The terms of the divers’ service were severe and might require them to spend years tied to their work in order to pay off debts accrued. Profits in the nineteenth century were apportioned with 20% being shared between the owner and captain of each vessel, 30% to be shared by the divers, 20% by the rope holders and 30% going towards provisions. The shares that went to each ghais and sa’ib would only be known at the end of the season when they would attempt to pay off their debts as well as buy necessary goods and presents for their families. Finally, at the end of the season, the crew would have to obtain a release from the naakhuda in the knowledge that they would most likely have to sign on again for the next season.

There is a little more detail established in a folder of documents assembled by British political interests in the early 1930s. Although they especially relate to the Bahrein pearling industry, it is probable that the practices described would also relate to Qatar if not elsewhere in the Gulf. It is notable that some of the terms vary from those I have heard used in Qatar, but whether this is a regional, temporal or dialect issue – or a combination, of course – I can’t say but it is noticeable that there is a requirement that stated nawaakhada with shi’a divers must land them ‘on the 4th Muharram and take them off again on the 11th of that month’. This suggests a strong Bahreini influence with its high proportion of shi’ite population.

According to the documents there were, at that time, four types of diving system used to differentiate the relationships within the pearling operations:

- Under the amil system the sea naakhuda finances his enterprise from the land naakhuda or taajir. Neither the taajir or the naakhuda charge interest on the money used to finance the pearling operation and, in return for putting forward the finances, the taajir has the option of purchasing all the pearls from the operation.

Compared with the eighteenth century Persian system described above, oyster shells were opened and inspected for pearls each night under the supervision of the naakhuda. On returning to land or with the arrival of tawasha boats – usually jalaabeet – carrying buyers, the naakhuda might sell them, with the knowledge of the crew, for the best price he might obtain. Two-thirds of the crew must be present to witness this operation. The document states that some of the pearls might be withheld and sold privately by the naakhuda, suggesting that the operation of selling pearls was open to fraud. - Under the madyan system both the land and sea naakhuda charge interest, with the pearls being sold to anybody. Apparently the taajir often compels the naakhuda to sell to him, though this is wrong.

- With khamas there are no advances made to divers and the pearling is a joint operation which several men being part owners or sharing a diving boat. One of the men must be appointed naakhuda with the responsibility for keeping the accounts. Under this system, the naakhuda receives a half of one fifth of the profits, the remainder going to the divers.

- Under the azal system, three or four men either hire or own a boat, or are contracted to one man, or go independently on the boat of a naakhuda. Capital is necessary for this character of venture, but is said to offer the least opportunity for cheating.

On returning from the pearl beds the pearls were handed over to the merchants who would then go through the collection with the naakhuda in order to make the first assessment of the collection. Using a set of brass sieves, the pearls would be sorted for size and then for colour and shape, the most perfectly spherical being the most valuable, but the baroque – those with irregular shape – also having value, particularly in the local markets.

This was a hard way to make a living, but it was one of the oldest ways to earn funds from the sale of the pearls, usually within the Indian sub-continent. It was the foundation for the wealth of a number of the merchants in the Qatar peninsula. But the lure of the nascent oil industry and the burgeoning Japanese culture pearl market effectively destroyed this way of life.

Regulation of labour

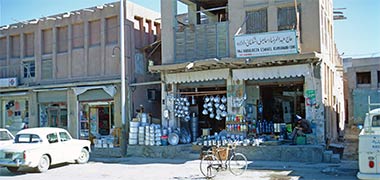

Doha’s central suq had been for decades the major area for the country’s agents to bring their goods to shore and move them to their warehouses. Daily a foreign workforce could be seen moving heavy goods around both to stores as well as to vehicles taking them around the country. Between jobs the workforce would rest by their cars waiting for clients to hire them. But this kind of work was not confined to central Doha but could be seen all over the peninsula.

The introduction of servants and the cessation of slavery happened gradually, coinciding to a large extent with the increasing wealth of the country. Elsewhere I have written a little on the complex way in which the West understands the term ‘slavery’ and the manner in which it was conflated with servants and their integration within families. There were still a number of slaves in the country in the early 1950s but the beginnings of the oil industry and its concomitant construction and operation required an increasing number of workers. This dramatically changed the labour system in the country. The pearl divers, fishermen, farmers and badu herders discovered that there was better paid work in the nascent construction industry. Men commonly earning ten riyals a month could earn between one and four riyals a day working in the petroleum industry. This had a number of effects, two of the more important ones being that:

- firstly, it precipitated the move from the traditional industries of pearling and farming, and

- secondly, encouraged the introduction and development of labour regulations.

While the diminishing character of pearling was mostly the result of external forces, farming was a necessary activity for feeding those living in the peninsula, and the movement and introduction of expatriate labour were necessary initiatives.

There were no labour controls in the 1940s and 1950s. Wages, hours, overtime, holidays, treatment and working conditions varied considerably but the new industry required the establishment of coordinated labour regulations. The first workers in the industry were, by and large, Qataris, with pearl divers moving to assist in the off-shore work while drivers, cooks and roustabouts were employed from the urban and badu Qataris. Qataris and other Gulf Arabs also comprised the unskilled labour force though there was the beginning of migration from the Indian sub-continent to provide, in the first instance, clerks and middle managers under mainly British management, and from Egypt to work on the farms.

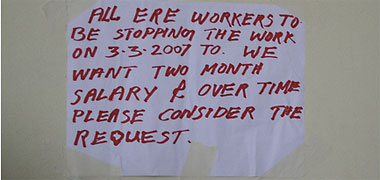

However, the initiatives marking the introduction of the new labour system was not without its problems, there being a number of strikes as workers attempted to improve their conditions. Some strikes were informal but a well-organised one in 1956 focussed not only on the British management but also on the Qatari regime, resulting in clauses being inserted into labour contracts making political activity illegal.