a collection of notes on areas of personal interest

- Introduction

- Arabic / Islamic design

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 01

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 02

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 03

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 04

- Islamic architecture

- Islamic urban design 01

- Islamic urban design 02

- Islamic urban design 03

- Islamic urban design 04

- Islamic urban design 05

- Arabic / Islamic gardens

- Gulf architecture 01

- Gulf architecture 02

- Gulf architecture 03

- Gulf architecture 04

- Gulf architecture 05

- Gulf architecture 06

- Gulf architecture 07

- Gulf architecture 08

- Infrastructure development

- The building industry

- Environmental control

- Perception

- The household on its lot

- A new approach – conceptual

- A new approach – principles

- A new approach – details

- Al Salata al jadida

- Public housing

- Expatriate housing study

- Apartment housing

- Pressures for change

- The State’s administration

- Society 01

- Society 02

- Society 03

- Society 04

- Society 05

- Society 06

- History of the peninsula

- Geography

- Planning 01

- Planning 02

- Population

- Traditional boats

- Boat types

- Old Qatar 01

- Old Qatar 02

- Security

- Protection

- Design brief

- Design elements

- Building regulations

- Glossary

- Glossary addendum

- References

- References addendum

- Links to other sites

Architectural styling

Grand Hamad Avenue has been mentioned earlier: it is a formal, wide insertion into Doha’s urban fabric on which were intended to be located major developments – implying that the buildings was intended to house important users, and that the architecture would reflect this. Here are details of two of the buildings constructed to the masterplan and which are not atypical of those that were built in the late 1980s.

If there can be thought to be a common theme, the buildings demonstrate a mixture of expensive materials, a range of surface treatments in terms of environmental control, arbitrary expression of internal functions and range of forms, and a lack of cohesion. It is difficult to ascribe blame either to the designers of clients, but I think the result is disappointing in that it could have been so much better. Admittedly, that applies to many if not the majority of buildings.

While the two photographs above illustrate a little of the manner in which modern buildings were being detailed on Grand Hamad in the centre of Doha, the New District of Doha bears witness to a wider variety of architectural styles as designers and their clients vie in their efforts to produce iconic buildings. The two towers shown here display something of the flavour of the disparity of styles that are developing in the NDOD.

These two cranked, glazed towers are also notable in their design. Here they are viewed contrasting with another of the styles that has developed in Qatar, this one based on a pastiche of traditionally based details. The cranked towers might be located anywhere in the world with their styling, but many owners require designs from their architects that will be notable, if not memorable. While this requirement may be in conflict with Islamic principles, it has become a feature of designs throughout the Gulf though it is not, of course, restricted to this part of the world.

On the New District of Doha, as well as within the existing town, development has proceeded apace with development stretching further north than was originally anticipated. While many of the new building designs, such as those above, attempt novelty in one form or another, there is a mass of less distinguished or distinguishable buildings that have their designs based on more standard constructional details, many of them based on a combination of plan forms established in the 1960s and 1970s, and two- and three-dimensional detailing developed from notional traditional buildings.

In the illustration above there is a view across new development within the existing Doha that seems interesting from three points of view. Firstly, many of the buildings are dressed in classic architectural detailing, an alien form in the Gulf. Secondly, there is little or no attempt to design for the environmental conditions of the region. But perhaps most interesting is how there is a degree of uniformity in the character of the architecture which supports the notion of anonymity that I’ve suggested in the previous paragraph is intrinsic to true Islamic design principles.

In the preceding paragraph I mentioned the more usual residential developments that made up the mass of new constructions dating from the 1960s and 1970s. You can compare that photograph with this, taken around 1985 and looking north-west from Umm al-Guwaylina over the West Bay towards the New District of Doha. In it, something of the design character of the taller buildings that had developed by that time can be seen. Interestingly, the majority of these buildings, with their façades facing south, have balconies providing a degree of solar protection to their windows during the summer months. But, as with the buildings in the photograph above, there is no local character in their detailing, nothing that tells you whereabouts in the world they are located nor is there a suggestion of the environmental conditions in which they were designed.

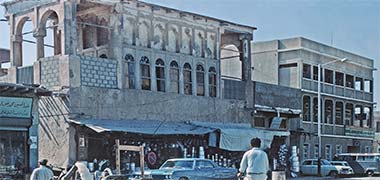

By contrast, this next group of three photographs were taken in 2002 of a building in Rumaillah, within the residential area a little way to the north of the Guest Palace. They show a little of the façade of a single building and its detailing that illustrate something of the history of the urban and architectural designs of the 1960s. The design of the building illustrates something of what has been lost in the more modern designs that have replaced it and other similar family houses, as well as buildings for residential accommodation designed to house expatriates in the early signs of the growing wealth of the State.

This building, and others similar to it, represented an aspirational belief in the development of the peninsula and the ability to fund buildings of reasonable design quality within the constructional capabilities and material availability of the times. I believe the building is dated to the mid-1960s, or perhaps a little earlier. Regrettably it no longer exists as the whole of the area on which it stood has been demolished – apart from the Guest Palace, a Royal family palace and the fort, with the roads being realigned in readiness for the intended redevelopment of the area, essentially related to the extension of the ‘B’ Ring Road into the New District of Doha.

None of the decorative design motifs are native to the peninsula but will have been imported by the artisans who produced them, most probably from the Indian sub-continent. The ogee arches over the windows on the ground and first floor are very typical of this influence, though the figurative decoration might be thought to come from elsewhere. There is a delicacy both in the treatment of the floral work as well as in the edge detailing of the arch and the lower edge of the surrounding band above the windows. The ironwork grille is simple but attractive, regrettably not coinciding well with the horizontal window glazing bars behind it. Despite this the windows have a delicate grace to them and, fronting directly onto the road, illustrate that the building was not constructed for Qataris to live in. Additional interventions to the building show how it has moved down-market in the years since it was built.

The twenty-first century has witnessed increasing criticism of the character of the new architectural buildings that are springing up, not just in Qatar but in other parts of the world. It might be sensible to look at the efforts made in the 1970s and 1980s to introduce not just better construction methods, but also better architecture.

First steps in Qatar

Because buildings such as those above have been admired or castigated by critics, it might be useful to take a brief look at how development in the New District of Doha began as it was here that it was hoped architectural design benefits would be made that would seed and improve the designs of future development. Compare those designs above with these next few projects, designed and built in the 1970s and early 1980s. This first photograph, taken in February 1984, shows the first developments and gives an indication of the heights and, therefore, density, planned for the area. In the centre is an island left to create a focus in the middle of the West Bay. The island is nine hundred metres at its closest to the Corniche, and the bay, from the Diwan al-Amiri to the Hotel is three kilometres.

The process of developing and encouraging higher architectural standards began with the identification of two prestigious projects to be constructed in the area to the north of the existing town – the University of Qatar, which was located deliberately some way to the north of the New District of Doha on existing land and, as a focus at the most visible point of the reclaimed land of the NDOD, the Hotel and Conference Centre, shown here as it appeared in 1985, both projects intended to illustrate a high standard of design and construction.

The Hotel and Conference Centre

The Hotel and Conference Centre, managed by Sheraton, was the first building to be constructed on the New District of Doha, the process beginning with the steel frame in early 1978, with more images being found on another page. The three sided pyramid contains a similarly shaped, twelve storey atrium and was, by its location, intended to be a focal point for views around the bay. There is an argument that, although it is obviously a Western-designed building and has no overt Islamic or Arabic detailing, it can be considered to fit into an Islamic / Arabic context through the geometry of its basic shape, the simplicity of its detailing, the introversion focussing on its central atrium and the use of deep screening to the façade. It may seem a little fanciful, but while the building is certainly made more memorable by its dramatic outline, I believe the argument has considerable merit and may be thought of as a modern version of a traditional caravanserai.

Four years later, the Hotel and Conference Centre development was officially opened on the 22nd of February 1982, that being the day which marked the accession of Sheikh Khalifa bin Hamad al-Thani ten years previously. This composite photograph shows the obverse and reverse sides of the silver medallion which was struck to mark the occasion and presented to guests. It is approximately 50mm in diameter and 4mm deep at the rim and was given in a presentation case which also allowed it to be displayed standing on its rim.

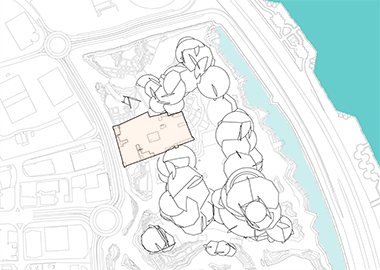

Since its construction there has been considerable development on the New District of Doha and, while the hotel is still the focal point marking the end of the bay when seen from much of the Corniche, this is not the case from the centre of Doha and anywhere to the east of that, where the building sits dwarfed by the extremely tall buildings built and under construction behind it. The aerial photograph above shows the complex with no constructions yet behind it.

Originally, the planning of the New District of Doha envisaged buildings no higher than eleven or twelve stories, an urban design decision that would have enabled the Hotel and Conference Centre to retain much of its character by its prominent location and shape. The only benefit is that its shape, to some extent, continues to enable it to stand out dependent upon lighting conditions in the bay. But, in many aerial conditions, it is sometimes difficult to pick out despite, as the second photograph shows, it being surrounded by considerable space given over to recreation, landscaping and parking. The next photograph shows the elevation of the buildings fronting the New District of Doha in 2010. The Hotel and Conference Centre complex dwarfed by the scale of the tall developments to their west.

This photograph was taken looking approximately east across at the New District of Doha from a point near the Fire Station illustrated in the photograph below. From the latter vantage point the Sheraton Hotel can clearly be seen on the point of the land fill and, particularly, its size can be readily compared with the new tower developments north of it. What is particularly significant is the manner in which the blocks have become an amorphous mass helped, in this case, by the poor visibility. This is one of the characteristics of massed blocks such as can be seen in New York and San Francisco, where famous landmarks are increasingly difficult to identify.

Seen by itself, as it once was, the Hotel and Conference Centre development still show the drama of their siting and design. This photograph illustrates how it is now looked down upon by the taller buildings behind it. The hotel can clearly be seen over the truncated pyramid of the conference centre near the bottom of the photograph, illustrating the importance of its location at the turning point of the West Bay. Behind it is the man-made island in the centre of the bay. The tall building just over the top of the hotel is the old Qatar Monetary Agency building marking the northerly end of Doha’s suq, the tall buildings to its right are situated on Grand Hamad Avenue and show the scale of development south of the suq which can be compared with the much taller development of the New District of Doha.

The images above were placed here mainly to show the state of early development within the West Bay in its early stages, with the emphasis being on the Hotel and Conference Centre development. But the area looks very different nowadays as illustrated in these two images.

The first aerial photograph, a night-time image looking approximately north-east, shows how much development there now is, not only at the tip of the filled area of West Bay, but also to its north where the Pearl development can be seen at the top of the photograph. The Hotel and Conference centre can be glimpsed on the middle of the right edge of the image, the night-time stream of traffic cutting it off from the tower blocks to its west.

The second aerial image, this time taken during the day, looks approximately north-west. What is evident from both photographs is that although the view across the West Bay from Doha shows the Hotel and Conference Centre dwarfed by the more recent tower block developments – as seen in the photograph four images above – there is actually quite a distance between it and the more recent tower blocks to its west.

Qatar National Development Exhibition building

In 1976 it was decided that the significant increase in construction now visible throughout the peninsula should be marked by an exhibition explaining in more detail how the state was developing. The intention was that the exhibition would be a resource accessible by nationals, expatriates and visitors to the state, that it would contain explanations of what strategies and projects were being pursued, and that it would be capable of updating as and when new projects were agreed.

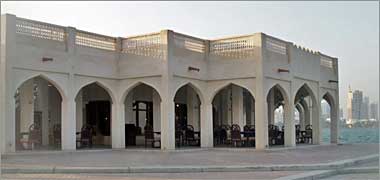

Regrettably the latter aim was not pursued, not by intent, but because the building housing the exhibition was not really suited to its purpose due to the increasingly large number of projects being constructed in the peninsula. The more modern element of the development housing the exhibition was demolished around February 2006, the older, traditional architecture remaining.

Once the decision had been made, and in order to move the project along quickly an unoccupied, old two-storey building immediately south of the Clock Tower and east of the Sheikhs’ masjid and Awqaaf offices was selected as it was seen to have the benefits of being close to the centre of Doha, had a parking area immediately outside, was adjacent to both the Sheikhs’ masjid and the Diwan al-Amiri, and would benefit from being renovated and detailed in the traditional style of architecture of the peninsula. As a part of this process, the building was amended slightly in order both to take it back to its remembered origins as well as improve its form by making it an exemplar of its type. This can be seen if you compare particularly the north-east corner of the building in the two photographs.

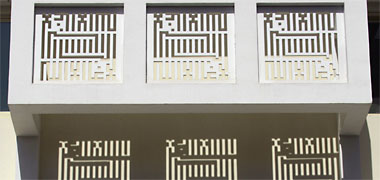

Using a team of craftsmen from the Ministry of Public Works, the building was completely renovated, its structure safeguarded and its surfaces decorated with a decorated naqsh carved plaster treatment, similar to other buildings being renovated in Doha and Rayyan. Housed in the courtyard behind the majlis facing the sea would be the exhibition centre within a contrasting modern structure to reflect the increasing use of the improved construction materials and new techniques being used by the state.

While the reconstruction works were carried out in the traditional manner, employing very similar methods and construction materials to those used in the past – perhaps with the substitution of cement rather than the traditional juss – the exhibition building was deliberately designed as a contrasting modern space because of a requirement for large clear spans to give flexibility in the placing of a variety of drawings and models, as well as for film to be projected.

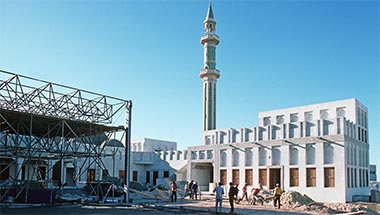

It was decided that the German Mero three-dimensional truss system would be used in order to give this flexibility, with a square plan module being selected. A few years later, a triangular version of the same system was to be used to cover buildings and provide shade at the zoological gardens at al-Shahaniyah in the centre of the peninsula. These two photographs, both taken in January 1976, show work on the two different characters of building in progress.

Note in the two photographs above – both images of the west wing of the new structure which was the first part of the development – that the roof structure, painted dark blue, had below it a separate Mero structure to which the exhibition panels, models and utilities would be fixed and from the top of which access with considerable flexibility could be gained.

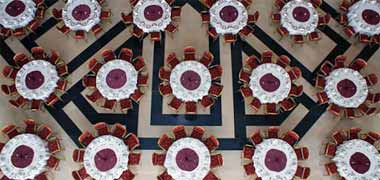

The projects displayed in the exhibition were selected to be seen as elements in a multi-media experience, with aural and visual presentations supporting drawings and models. The view above, taken within the exhibition area and looking up into the ceiling space, shows something of the way in which panels were suspended from the connecting rod structure. It is also possible to see the open cabling trays which were deliberately left exposed to view.

In setting out the background information for the projects, all descriptions, written and spoken, were bilingual with Arabic preceding English. The exhibition was a popular destination for those wishing to know more about the intended progress of developments within the peninsula, as well as experiencing a new approach to the refurbishing of the traditional architecture in the old building.

In the last two photographs above, which were taken within the exhibition hall show, models of the new university can be seen in the first image as well as, in front, a model of the tower that had been planned for the centre of West Bay, but was eventually unbuilt. Left centre are photographs of the Rumaillah hospital, then under construction. On the far left is one of a number of video screens that displayed short films mainly on the physical development of the state.

In 1983 a short film, ‘Qatar – Quest for Excellence’, which won an award at a European film festival, was added to the exhibition as well as being shown on television.

Seen at the bottom of the photograph above, is a model of Doha and the West Bay which was designed and built for the exhibition. It allowed visitors to illuminate the different projects using a button system.

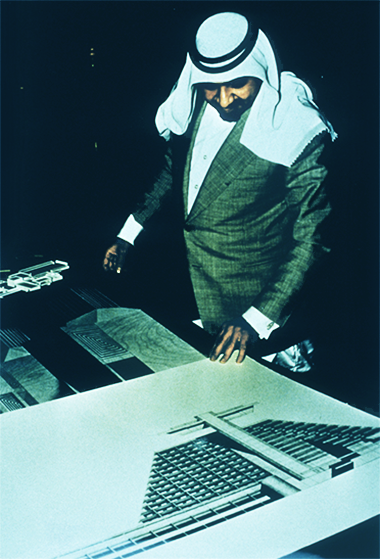

Upper left Sheikh Khalifa can be seen looking at drawings of the projected Hotel and Conference Centre soon to begin construction across West Bay at the far end of the New District of Doha, the image reproduced in the last photograph at a larger scale.

Qatar University

The next group of photographs shown here illustrate something of the character of the plan of the University of Qatar, designed around the same time and located, deliberately, some way to the north of the New District of Doha in order to keep it relatively private.

This first aerial photograph is taken from a government press handout showing the project as it appeared a few months prior to its opening in February 1985. The library is that part of the development nearest the camera with the University’s administrative functions contained in the building on the right. The men’s and women’s colleges are contained – and separated – within the structures running away from the camera.

The general treatment of the architecture of the University details the buildings in such a way that restricts light and views into and out of the building. In the Administrative building, this intent was married with a need to keep as much of the walls clear of opening as practicable, resulting in a building which has considerable bulk and stands in direct contrast to the heavily articulated elements of the faculty structures. On top of the building, some of these elements were used, notionally to bring light into the building but also assisting, with the entrance stairs, in bringing an understanding of scale to it.

Situated on rising ground the University was designed to make an impact on those viewing it from outside as well as moving around its buildings. At this point in time it is difficult to imagine how striking the buildings will have appeared to those on campus, but I’m aware of this effect from personal experience. By night they were even more striking, as this photograph illustrates, and formed a useful backdrop for those on campus, both formally and informally.

Time has now seen the university incorporated within the NDOD by encroaching development from the south, east and west. Designed by the late Egyptian architect, Kamal al-Kafrawi, the design is premised on a geometrical plan form of octagons linked by squares, and with three-dimensional devices on top of the octagons that are based on the traditional abraaj al-hawwa and theoretically provided either light or ventilation, depending upon the manner in which they are deployed and detailed.

This photograph illustrates something of the conceptual design of the development with the abraaj al-hawwa dominating the skyline, and the mushrabiyaat screening the windows, clear elements of the design. The two main walkways are aligned to run approximately south-east to north-west which, while argued to optimise shading of pedestrians, tends to act as a channel for the shamal winds.

This is a detail of the device that was designed to allow light into the building. It is clear that it has a definite Islamic feel in its use of natural ventilation and lighting techniques, massed concrete construction, screening and strong geometrical two- and three-dimensional forms. Having said that, and despite its having been given the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, there is criticism that the abraaj al-hawwa are unable to ventilate a two-storeyed volume, that dust infiltration is a problem and that the octagons are difficult to fit differing teaching units within.

In this photograph, taken in July 1982, some of the basic elements can be seen here being assembled to create a part of the main complex. The concrete columns have been wrapped to protect them from accidental damage, capping units stand on top of them and await the placing of the wind or lighting towers on top of them. The walkway threads between the columns and one of the pre-cast spiral staircases has been placed and awaits its balustrade. The quality of the work in the newly established pre-cast yard was extremely high and contributed to the success of the finished project.

Inside the building, the circulation system is driven through the combined octagonal and square. At ground floor level this has been easily accomplished but, at first floor level it becomes more obvious, the route being articulated as a walkway suspended from the structure and easing its way between the columnar and wall structural elements as shown in this photograph, taken in January 1985.

Taken in February 1985, this photograph shows how decorative coloured glazing panels have been incorporated into some of the distinctive towers, and suggesting something of the quality of light that is able to reach the ground floor from that posisition. But it also shows how fluorescent lighting tubes have been used to provide lighting within a strong decorative pattern in keeping with the architecture of the building.

While these may be valid in differing degrees, the fact is that the scheme represented a significant advance in architectural design within not just the country, but the region, and one that, with the Hotel and Conference Centre stood as exemplars for future projects.

More than that, both projects were also designed using methods that were novel in the country. The University was constructed with high quality massed pre-cast concrete panels and in-situ reinforced concrete coffered floors, as can be seen in this aerial view of a part of the development under construction. The quality took some time to achieve involving considerable research and casting in the pre-cast yard established for that purpose.

There are also some notes on one of the Planning pages relating to the University.

Both the University and the Hotel and Conference Centre used construction systems and methods not previously seen in Qatar. Contrasting with the pre-cast elements of the University, the Hotel and Conference Centre was constructed with a steel frame permitting the buildings to be erected quickly on concrete piles drilled through the newly placed dredged fill, with steel floors and high quality pre-cast concrete panels placed and hung from the frame. While the completed projects embodied Islamic design principles, their methods of construction helped to establish construction techniques that would form the basis for further projects. This first photograph was taken from one of the upper floors of the open steelwork looking down on the beginnings of the Conference Centre element of the complex. Behind the Conference Centre is the site formed for the location of the Diplomatic Area of the New District of Doha. The middle photograph shows a riveter at work assembling the steelwork. Some of the corrugated steel floor plates can be seen, though not yet all in place. The lower photograph shows the steelwork under erection for the distinctive Hotel element of the complex.

Rumaillah fire station

From early days in the development of Doha, fire stations existed at the airport, and with the Central fire station located on the Rayyan Road just west of the centre of Doha and south of the Diwan al-Amiri. But as the town expanded the 1980s saw the construction of a more modern development at Rumaillah, on the high ground opposite the Police fort. The fire station on the Rayyan Road had access to the existing road structures both on the Rayyan Road as well as south onto Abullah bin Thani street. But these roads did not have the capacity to enable emergency vehicles to move around the two rapidly. The benefit with locating a larger station at Rumaillah was that it was able to take advantage of the newly developing road structure to move around Doha more rapidly. In the second of these two photographs, taken in 2008, emergency Civil Defence vehicles can be seen rolling out in response to a call or shout.

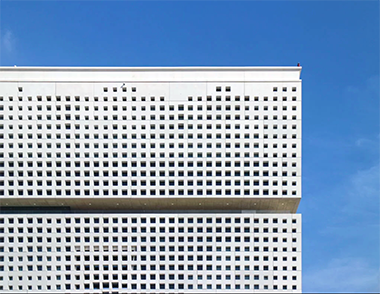

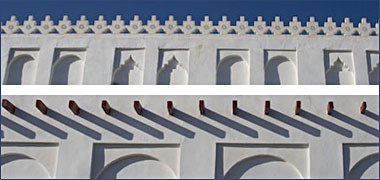

The building presents itself to the outside world with a solid block at ground floor level below a brise soleil façade protecting the glazed windows behind it, above which were pre-cast concrete shading units. Although the treatment of the façade took scale away from the building, the brise soleil have a tenuous link with Islamic or Arabic patterns in their three-dimensional detail and, as such, I believe it was a reasonable interpretation of Islamic / Arabic design in terms of both the geometric interpretation as well as the principles of privacy and external environmental control. Adjacent to, and at right angles to this block was a two-storey structure, essentially a garage for the emergency vehicles, a photograph of which is shown two images below, taken in 2008.

The detail of the façade in the first two photographs illustrates more clearly the relationship with geometry, there being a hint of the double axe head in its three-dimensional shaping typical, in its two-dimensional form, of Qatari naqsh detailing or of the traditional mushrabiya, perhaps more common in northern Muslim countries in timber form. I believe the original building was designed by William Sednaoui, but am not sure.

Contrasting with the filigree detail of the main building’s façade, the garaging of the emergency vehicles was housed in a building set at right angles. Above the first floor windows is a feature perhaps designed to act as a solar shade, but probably not too effective, but a much stronger design feature – which is also an element of the main building – is an inverted and large interpretation of the traditional Qatari maraazim water spouts. A large sign announces the building’s function as the ‘General Administration of Civil Defence’.

This photograph was taken towards the end of 2013, by which time the title of the building had been changed while continuing to provide services for Civil Defence functions of the Ministry of the Interior. I had thought it was being demolished as being no longer capable of responding to the State’s modern requirements, but the photograph was taken while the building was in the process of being re-purposed, an exercise begun in 2012 under the aegis of Qatar Museums. It was intended that the structure should be kept and the façade redesigned, the building now being referred to as the Fire Station Artist in Residence building.

The structural form of the building is clearly shown in the above photograph with its primary and secondary structural elements evident. This is particularly evident in the treatment of the dissolved structural corners of the building as well as in the distinction between the office elements forming the top of the building and their contrast with the different functional parts at ground and first floor.

This photograph was taken at the beginning of 2020 and shows the old fire station building – together with the old fire engine displayed with its number plate 1948 in front of the building – restored and functioning in its new rôle as a centre for the development of arts. The image can be compared with one of the images above of this note. While the old fire station sign is still evident about the entrance door, facing south-west, the façade displays the building’s new use as a ground for the application of strong graphics clearly visible from the adjacent roads and Civil Defence roundabout.

Care has been taken in the redevelopment of the building not only to keep the original façade design but to reorganise the volumes within the building in order to cater for its new use as a series of spaces to be used by future artists in residence and the setting and presentation of exhibitions. The elements forming the main façade appear to be the same, or very similar, to those originally used, and there are few changes to the original design of the main building other than its top. In this photograph of the rear of the development, facing approximately south, the spaces previously occupied by the fire appliances can be seen open for use by the Fire Station Artist in Residence operations. It is envisaged that there will be a number of adaptations made in order to cater for the needs and requirements of the future invited artists and exhibitions.

Qatar Monetary Agency

At around the same time the previous three buildings were being developed, two other buildings were being constructed in the centre of Doha, both on the Corniche, one each side of Government House – the Qatar National Bank on its east side and the Qatar Monetary Agency to its west. The Qatar Monetary Agency, shown here under construction in these two photographs, was also designed as a modern, Western-style building. The first photograph, taken in March 1974, looking north-east from the manara of the Sheikh’ mosque, shows how the construction depends upon a standard column and beam concrete construction, with short blockwork walls on the periphery of the floor slabs upon which internal glazing was mounted. Outside this, the glazed, gold-coloured reflective façade was hung away from an inner skin to give the building its distinctive – for that time – character. In theory air was able to move upwards between the two skins of the building, however the long axis of the building is oriented north-south, maximising the amount of façade facing the rising and, particularly, setting sun.

There is a photograph of the Qatar Monetary Agency under construction in March 1974 a little way above. Assembled from two images, here is a wider view from which that image was taken. It shows something of the development of the urban scene in Doha at the beginning of the 1970s when the first burgeoning of building took off. Here the Corniche is in place with the medial planted, there are single storey buildings between the Corniche and inner road, and there are still traditional buildings to be seen in the suq. At top right is the Gulf Hotel, top centre and designed by the architect William Sednaoui, the power station at Ras Abu Aboud and, top left, two freighters moored on the port jetty.

This is one of the photographs issued by the Ministry of Information illustrating the progress Qatar was making in its development. It is likely to date from 1975 or 1976 and views the building looking south-east from the Corniche. Behind it is the old Government House and, behind that, the Qatar National Bank, then under construction. Beyond that is the Municipality building, also designed by William Sednaoui, on the other side of the junction of Jabr bin Muhammad Street with the Corniche, and opposite the entrance to the port development.

Deliberately contrasting with the more formal image above is this photograph taken from the Country Craft jetty in November 1975 and showing the distinctive colour of the building’s cladding when lit by the setting sun at dusk, a view which enlivened driving along the Corniche in the evening. This was seen to be a novelty at the time, contrasting dramatically with the more common concrete and cement rendered constructions of the old, and most of the new buildings.

Qatar National Bank

Abdullah bin Jassim street was the location for most of the banks in the early development of Doha. This had much to do with the government’s filling of the sea in front of the old foreshore to create new land upon which could be constructed buildings for government, as well as those required in the increasingly rapid development of the state and its different infrastructures.

This photograph, taken in 1972, shows the original Qatar National Bank building facing north with the Darwish Cold Stores and its adjacent masjid, and the Diwan al-Amiri facing down the road. The Clock Tower is hidden by the buildings on the left. A little way to its east were the Chartered Bank, the British Bank of the Middle East and the Mashareq Banks.

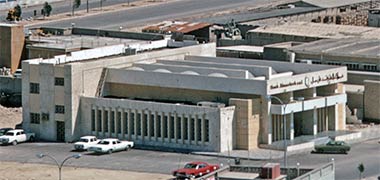

Here is the new Qatar National bank showing it with its original façade, the photograph having been taken in the 1980s looking, approximately, south-west. The corner of the Ministry of Finance extension to the old Government House can be seen on the right of the photograph and, on the left, a commercial development which housed offices together with the headquarters of the Standard Chartered bank; since the time of this photograph, that building has had two facelifts. Note the design of the Qatar National Bank where the narrow fenestration has been provided with projecting cheeks, a design feature that restricts light and, therefore, heat into the building, while helping illuminate naturally as deeply as possible through the vertical orientation of the windows.

These two photographs were taken more recently of the Bank’s east-facing façade, which was seen to represent the new style of architecture derived from the office buildings of the West. As such it might be argued that its international face was reflected in its design though, prior to the decision being taken to amend the original design – I am unable to supply the date – it was suggested that it should better reflect national traditions. As is the case with many glazed buildings, it is unsuited to the environment of Qatar, as well as having its long axis oriented north-south, maximising solar gain on its east and west façades. Nevertheless, the façade derives some benefit from its reflective surfaces. This feature also mirrors buildings to its east, visually breaking up the flat façade as can be seen in the top photograph. Note how, in the second photograph, the logo on the top right corner of the façade has been amended to include the Roman initials of the bank. Incidentally, the corner of Kenzo Tange’s extension to old Government House, can be seen behind the bank.

This third photograph shows the Bank’s headquarters looking south-east from the Corniche, and illustrates the manner in which the façade of its northern elevation has been treated. To some extent this appears to be a homage to the design of Kenzo Tange’s Ministry of Finance extension, immediately to the west of the Bank, where prominence has been given to the building by creating a large, framed entrance. In the case of the Ministry of Finance, the framed design relates to the large entrance hall behind its north façade; in the case of the Bank, the framed design creates a sense of prominence without being able to reflect a space behind, a common problem with retro-fitted designs, but one that introduces another design issue as the marking of the respective floors in the building on this façade is apparently at odds with their marking on the east and west façades.

The Citibank building

Citibank were late entrants to the financial scene in Qatar, the Arab, Standard Chartered, Grindlays and the British Bank of the Middle East at least, having preceded them. Citibank constructed what was then a novel building at the east corner of the junction of the ‘C’ Ring Road and Salwa Road. As can be seen in this photograph, taken in 1980, the building was a basic box but, around it they erected a screening system of brise soleil providing both a degree of protection to the basic structure as well as a view through the screening.

The HSBC bank building

Taken in January 2002, this photograph is of the HSBC bank building that was situated to the west of the Qatar National Bank facing onto the West Bay over the Corniche. It no longer exists. At the beginning of 2008 it was demolished along with some of the buildings lining the Corniche in the centre of Doha, in order that the State might develop a more green urban park backdrop to this important route, and with HSBC’s headquarters being relocated to the Mesaieed Road.

The design for the building appears to attempt the incorporation of elements on its corners reflecting the sails of traditional sailing craft, while further reminding those with an interest of its Arabic setting by the incorporation on its north and south façades of what might be thought to be an Islamic arch. Above this sits the unfortunate HSBC logo. The fenestration design to the building’s east and west façades is the same – as is the treatment of those to the north and south – there being no difference in detailing to take account of the massively different thermal loadings on the different façades. It was neither a sensible or attractive design.

The BBME bank building

The British Bank of the Middle East began its operations in Qatar in 1954 and, having been taken over by HSBC Bank Middle East Limited in 1959 claims, in 2018, to be the largest bank in the country. This aerial photograph was taken in 1974 and I believe is of the bank situated immediately to the east of the Mushareq Bank on the north side of Abdullah bin Jassim Street. Later it was moved further west along the street to a custom built office block, shown below. The design was, essentially, a simple shed with clerestory lighting along its long north-south axis. The façade was a blank wall with some elaboration around the entrance over which was its name and with its logo mounted on the right.

This photograph was taken in August 1989 and is of the new building housing the offices of the British Bank of the Middle East. Situated on Abdullah bin Jassim Street, this view of it was taken from the old jetty, looking south over the Corniche, the building facing north and looking across the West Bay. It was designed to reflect the strength of the bank with the corners visually pronounced and the bank’s logo centred high on the façade.

The building with a blue façade to the left of centre of the photograph is the first floor of the al-Mana showrooms, their residence being behind it. The single storied Chartered Bank was to the left of the BBME building. There were a number of banks in this area, mostly constructed before this building and being only a single storey high.

The Mushareq bank building

The Mushareq bank, originally the Lebanese bank, was also located on Abdullah bin Jassim street, but on its north side, to the immediate west of the British Bank of the Middle East. This photograph, taken from the manara of the Grand mosque, shows the bank facing onto Abdullah bin Jassim Street; a part of the Corniche road can be seen behind it. The bank was originally the Bank of Oman and based in Dubai, beginning its activities in Qatar in 1960.

The building was constructed in 1972 and its architecture was elaborate for its time. The main hall was a high single storey space with a lower run of offices on its west side and a two-storey block on the north. Light to the main hall was provided by roof lights oriented towards the east.

The Standard Chartered Bank building

The Standard Chartered bank was also situated on Abdullah bin Jassim Street, but whereas the Mushareq bank was on its north side, the Standard Chartered bank was diagonally opposite, on its south side. A smaller, earlier building it was a single storey structure designed in a Western style. There was minimal glazing to its interior on Abdullah bin Jassim street, but a different architectural treatment and a more open façade on the side street leading south along the west side of suq waqf toward the central maqbara, this glazing being covered by an external decorative screen.

The lower aerial photograph looks at the bank from the north-east over the top of the old Customs building. Behind the bank are the courtyard and buildings of the neighbouring property belonging to the al-Mana family. This combined a residence with commercial showrooms and storage spaces. It is worth remembering that, at one time, the al-Mana property – seen in the first photograph with two attractive bowed windows above the showrooms flanking the main entrance – this north face of the al-Mana property would have been along the approximate line of Doha’s foreshore.

The bank, known as the Eastern bank was, until 1954, the only bank operating in Qatar. The Standard Chartered bank was created in 1969 with the amalgamation of the Standard bank of British South Africa and the Chartered bank of India, Australia and China.

Grindlays Bank building

The history of banking in Qatar, in fact globally, is complex and this is not the place to discuss it. However, the Othman or Ottoman Bank opened a branch in Qatar on 1st November 1956 but was bought by Grindlays bank in 1969. Grindlays were subsequently taken over by Standard Chartered in 2000, acquiring it from ANZ who had bought it in 1984, but changed its name to ANZ Grindlays in 1989.

Probably based on land pricing or ownership, Grindlays bank was situated away from the other banks on Abdullah bin Jassim Street on the Rayyan Road between Electricity Street and al-Diwan Street, its frontage facing the former and Rayyan Road with a strong presence for those driving west along the latter.

It was an imposing, narrow, tall two-storey building set at 45° to the junction, with splayed corners. Unfortunately, and as can be seen here, the only images I have of the buildings are aerial photographs with differing colour faithfulness, but all taken from approximately the same angle, the north-east.

The architectural treatment of the building had rendered concrete block walls at each splayed end, with vertical columns running the full height of the main façade and containing glazed fixed windows. Entrance to the building was effected below a small projecting shade device. A tall band of rendered masonry projected slightly to form a parapet hiding the building’s plant and equipment, and giving the façade of the building a solid, classical feel.

It is probable that foreign banks saw a need to appear both Western and financially sound, a rationale that, in the West, saw banks being designed along classical lines with heavy masonry and relatively small glazing and, in Qatar, ignoring the traditional architecture of the peninsula.

The Arab bank building

More of a landmark than those immediately preceding it, perhaps, was the Arab Bank. Situated at the junction of Jassim bin Muhammad and Musheirib Streets, it faced due west over a roundabout that incorporated a fountain feature. This was a rare feature in those days, so the roundabout naturally took its name from the bank – the Arab bank roundabout. The building was provided with a large scale mushrabiya, but it is likely this provided little protection against the setting sun shining down Musheirib Street.

The Radio Station

Prior to the development of a television presence in Qatar, a radio production and transmission studio was developed to the west of the New District of Doha, and south of the road leading from the Corniche to al-Markhiya and Medinat Khalifa and, from there to the north, south and west of the peninsula. The facilities were established in June 1968 in Arabic with English transmissions following in December 1971.

A transmission aerial was situated to its east, surrounded by a steel fence and secured with a permanent guard. This image, taken much later in 1976 and part of a much larger photograph, shows the original production studio as the single storey structure.

The Television Station

Qatar developed its first production and transmission facilities for television programmes immediately adjacent to the existing Radio Station in 1970. This was a rapid response to a perceived need by the State and saw the first television transmissions being made in that year. Marconi provided the technical knowledge and equipment for the initiative, and the building was designed and erected round it by the Engineering Services Department of the Ministry of Public Works. A single channel broadcast in black and white for three or four hours a day.

By 1974, the facilities in the small station were developed in order for it to begin broadcasting in colour. This view of it was taken in 1976 and is a detail of a larger photograph. The image shows the relationship between the pilot Television Centre and the older Radio Station in a larger selection from the original photograph, and is looking approximately north-west.

From its beginnings with a single channel in 1970, the growth of Qatar’s national television station were developed, with a second, English channel introduced in 1982 and a television satellite channel in 1998. Qatar is also known for the al-Jazeera channel, though this was a private but initially Government-financed broadcasting initiative, intended to reach a world-wide audience. This photograph shows engineers in the control room of the new Television Centre building in March 1976.

For the physical building, external consultants were brought in to advise on the equipping, staffing and layout of an expanded facility, and the Ministry of Public Works was again asked to produce its external skin.

In this second photograph, a more detailed image of the first, it is interesting to note that the construction of this modern building utilised the traditional material of timber for the external scaffolding, the more advanced building systems yet to become the norm in the building industry.

Although there had been a smaller, pilot studio, the building was interesting in that its internal requirements were novel at that scale to the country. This photograph shows it under construction in, what can be seen to be then, essentially a desert site.

Security dictated that the building should be located some distance from a secured perimeter, and the State required a modern building, by which it was meant at that time, a Western-styled design would be a requirement. The use of the building to project Qatar initially within the peninsula but hopefully to a wider audience, also meant that it was mainly to be seen from a distance – apart from those using it, of course.

In the event the building might be considered to be similar in form to a traditional fortified structure with strongly modelled, squared corners articulating its vertical circulation, and a contrasting continuous horizontal treatment of the external devices shading an inner building skin, thus safeguarding flexibility to offices on its periphery.

Louis Khan appears to have been an influence in the design of the building, but in this there is also a coincidence with the traditional architecture of the peninsula. This photograph of the treatment of the windows on the corner stair towers shows something of his influence in the detailing of the window surrounds in the need to keep the sun from striking the glass.

As noted above, the façade of the building was treated very differently from its vertically expressed corners. Here the screening of the skin of the studios was held at some distance from the building with horizontal concrete bands marking floor levels and horizontal louvres, sloping out and down, to ensure there would be no solar gain on the skin of the building.

There is some ambiguity of scale in its façade, but this is a reflection of its internal spatial arrangements, the only hint of scale being given by its entrance canopy. While there are no overt stylistic devices tying it either to Islamic designs or traditional Qatar architecture, its protective form is in keeping with the Islamic traditions both of security and privacy. In this sense it might be considered similar conceptually to both the Hotel and Conference Centre and the Doha Club, the latter now demolished. The building came at a pivotal time in the architectural development of the country.

Qatar Earth Satellite Station

This image, taken from official Qatar Government material, is placed here as a marker as there needs to be more information provided. My understanding is that it was one of a number of earth satellite stations installed along the Gulf which aircraft and ships could use in navigating their passages. The Station was situated on the south side of the Salwa Road at Mukaynis, and was later developed with more arrays, but I’m unable to put dates to either this installation or the later ones.

Al Hitmi office building

Contrasting with the modest glazed curtain wall of the Qatar National Bank shown above, this building is being completed towards the end of 2009, a little further east along the Corniche, opposite the entrance to the port development on feriq al-Salata. It represents yet another style of architecture introduced from the West. I don’t know the name of the architect, but the building has similarities with those of Frank Gehry and his disciples. My interest here is that the building has been designed in what is known as the deconstructivist style, its particular characteristics being not only the denigration of social and cultural issues, but also functional and, perhaps, environmental. Externally the traditional forms of building have been eroded by lines and faces that depart from the orthogonal, and material, colour and detailing that make scale difficult to read and relationships with it, for those moving in and around the building, problematic.

As a form of sculpted building it may have much to commend it to a Western designer, but Qataris have a strong socio-cultural past. The surroundings they now find around them incorporate an increasingly bewildering array of styles, few of them developed from the traditions with which they might find an empathy. Some Qataris are now disturbed by the apparent erosion of their past as the urban scene increasingly incorporates iconic buildings disconnected from each other and antipathetic to their traditions. Buildings such as this, which are far removed from local tradition and represent the incursion of the global market into Qatar, are likely to be increasingly viewed with suspicion as much for their unfamiliarity as for what they represent.

Liberal Arts and Science building

These two photos are of the Liberal Arts and Science building in Education City, and also illustrate the use of Islamic / Arabic design principles of privacy and external environmental control, but in a very different way from the preceding example. The burj al hawwa are functional and vent the car parking areas below the building but look weak in their balance with the basic structures below them; and I believe the long horizontal skylines are inimical with traditional Qatari architectural vocabulary. However, I very much like the patterning of the façade which, while obviously unrelated to traditional Islamic patterns, is very much reminiscent of Penrose geometry, the eighteenth geometric pattern, well suited to a modern building in the Arab world. The night photograph shows how the façade is set away from the internal wall of the building, providing a high degree of solar screening.

This detail photograph looks up into one of the the external corners of the screen, illustrating the devices which hold the screen panels away from the containing wall of the building and which establish and define a consistent gap between the individual panels. This separation of panels goes a little way to break down the scale of the façade but, more importantly, the fixings also permit some thermal movement which, were the panels to touch, might cause damage at their junctions.

This first of three photographs shows a more detailed view of the pattern of the façade of the Liberal Arts and Science building. It illustrates the mobility created by the lines of the panel junctions, a mobility created by our natural inclination to read movement in static patterns. I mentioned above that, while the patterns have no obvious relationship with traditional Arab geometry, they have a feeling of more novel pattern forms. The patterns have neither regularity nor repetition though, in a similar manner to traditional Arabic geometry, there is implied continuity beyond the decorated plane on which they sit. The architect writes that ‘Respecting the culture of abstraction and innovation of the geometric pattern, a quasi-crystal pattern is used for the exterior façade, aluminum shades, and aluminium louvers (located at the crossing points of the flexible learning areas). This geometry consists of three basic configurations, 90°, 60°, and 30° parallelograms, which start from a single point and expand infinitely without repetition’. This is, of course, Penrose geometry, written about previously.

There is an interesting detail at the corner junction, which brings up an old architectural issue relating to the honesty of design. In the second photograph, a detail of that above it, the junction lines on the two façades meet each other on the corner. In design terms this implies that there is continuity of material, even though it is obvious there is not. In the detail photograph below it, the junction lines on the two façades specifically do not meet at the corner. This latter detailing shows the honesty of the material used: thin panels are being held away from the building and can not be thought of as being structural. Yet the two details are immediately adjacent to each other so you have to wonder if this is deliberate or accidental. If the former, what might have been the reason? In writing about the enveloping pattern the architect implies there is a continuity of pattern, in which case I would have thought that all corners should display continuity of junctions. Whichever might be thought correct it is, nevertheless, an interesting building to look at, and one that moves Arabic or Islamic architecture forward in the peninsula.

These photographs were taken within the Liberal Arts and Science Building in Education City and illustrate another approach to screening, one which is not a reflection of external environmental concerns, but appears to be used here to provide a degree of privacy while introducing a strong textured character to this internal space, one which contrasts architecturally with the clean lines and surfaces of the adjoining glass and plaster. It is a classic mushrabiya both in design detail and design intent, albeit on a larger scale than a traditional mushrabiya. As such it continues an element of traditional Islamic design vocabulary, though not one that is particularly characteristic of the peninsula due to the building forms which developed which resolved many of the issues relating to privacy in a different manner.

The geometric design of this perforated screen seems to be similar to the geometric patterning of the solid screens forming the external façade of the building, both of them having a similarity to designs used in the Masdar development in Abu Dhabi which appear to have a basis in the geometry discovered by Penrose. Whether or not this is the case, the screen has a very strong presence within the space and lit from the front, while allowing a degree of permeability as can be seen in the upper of these three photographs. However, by the same token, the effect can appear untidy when the elements behind the screen do not align with the geometry of the screen. The lowest of the three photographs shows how the screen is fixed back to the wall behind with a neat detail incorporated within one of the squares of the screen.

College of the North Atlantic

There appear to be similar design imperatives behind the architecture of the College of the North Atlantic at Duhail, close to the original Qatar University designed by Kamal al-Kafrawi. This first photograph shows the theoretical similarity in the treatment of façades with the provision of an outer screen wall to create protection for the inner wall. Here the treatment takes two forms which provide different degrees of protection. On the left, where there can be seen to be direct sunlight on the building, there is an almost solid protection provided by a wall with a small percentage of openings arranged in an abstract, decorative pattern. Unlike the façade of the Liberal Arts and Science Building, this façade has an arbitrary design arrangement within the form of the façade as well as a relatively arbitrary skyline. In addition there is an external cranked design element moving up and over the building whose only purpose I can make out is to break down the continuity of the long façades.

On the right wall – one which also receives sun – there is a much more open design which, while providing some solar protection, will allow relatively large areas of glazing and, consequently, views out of the building. If designed properly, the design of the external screen will have been calculated to provide solar screening to the windows during the hottest part of the year while allowing some solar ingress during the cooler part of the year in order both to provide warmth to the building as well as a degree of visual interest in its movement across floors and walls.

External protection from the sun and rain for those moving in and around the campus seems to be well provided for. In this photograph there are covered walkways which are protected not just by their high ceilings, but also by a vertical screen which I imagine is provided in order to give additional protection where the sun is likely to penetrate obliquely below the high ceiling. The second photograph shows a detail, I believe, of the vertical screen illustrating the extent to which it provides protection from the sun.

The importance of providing a protected external pedestrian system can be readily seen in the above two photographs where people are moving around the campus in shade. While it is pleasant to walk in the sun on cold days it is more important to have protection from the sun and rain. Where there are both possibilities, pedestrians can enjoy the best of both worlds, but this is not always a viable possibility.

What is important to note is that this degree of provision is mostly only possible where there is a coherent design strategy for a discrete urban design entity. An educational campus is one obvious example but it is a pity that it can not be developed in other pedestrianised areas, much as existed with the traditional sikkak, particularly the old covered suq.

One final note on this project. You will see that the landscaping follows a more Western tradition with some three-dimensional modelling of the ground but no attempt to use the landscaping to provide environmental amelioration by, for instance, planting against the building, nor to create the degree of formality of traditional Islamic gardens.

Liberal Science and Arts building

Compare the screening provided to the Liberal Arts and Science Building’s façade and the College of the North Atlantic above with this screening on the Hamad Bin Khalifa University Student Center which illustrates a very different design approach. While those above present façades which form the external skin of the building, here the architect has draped the building with a light, freeform skin through which the building and its structure is still apparent – though this may differ depending upon the manner in which light and the sun strike it with respect to those looking at it. The immediate benefit of this is to create a lace-like moving shadow within the building which contrasts with the more regular geometry of the columns and other elements of internal structure and finish. But this character of screen design appears to work better when viewed from the inside of the building than it does from outside.

This patterning suggests natural elements such as the branches of trees acting in contrast to the lines of the building, particularly those of the columns which have allusions to branched trees. While it is assumed that the screen is far enough from the inner face of the building to facilitate cleaning that face – and the screen itself, of course – there are a number of disadvantages to this type of treatment. Firstly, and from a technical point of view, the screen might still allow considerable heat gain on the windows behind it. The issue of security is probably not a real concern here but, from a design point of view there is significant ambiguity in draping an amorphous shape over a regular structure, particularly as there appears to be no design connection between the two elements of screen and screened.

Qatar Education City convention building

The principle of using the external skin of a building to provide insulation to its interior is one that seems to be difficult to learn. Many of the above examples show a range of responses to the environmental conditions obtaining in Qatar, but many still rely on other design devices to produce an architectural effect. Designed by Arata Isozaki, the Qatar Education City convention building shown here has a frontage designed conceptually as the branches of the sidratree, a tree that holds a special meaning for Muslims, being associated with knowledge and learning. The enclosure of this building may indeed respond to the environmental conditions in which it is situated, but it is the front façade that that holds the interest of the viewer, illustrating a literal representation of the branches of the sidratree. This is a building that is not seen to be viewed in the round, but from the front, the tree branches being constructed as a massive steel structure, but disappointingly to me, supporting a minimal canopy and not one that reflects the concept promoted by the Qatar Foundation where the branches go on to support the leaves, flowers and fruits which represent the individuals benefitting from education. From a local cultural point of view it is worth noting the association of the branches of the sidratree with their literal architectural interpretation. Here is an asymetrical design placed against the regular geometric fenestration of the shell of the building; the extent to which this is might be considered another Western imposition is debatable.

Healthcare buildings

While I believe this building is part of the Ministry of Public Health’s later Primary Healthcare operation, the interest to me is in the use of horizontal solar screens in Qatar. As you can see, the projecting first floor and roof provide a degree of protection to these south-facing openings, but the projecting horizontal louvres create additional shade to the openings from a high sun. In the winter months when this photograph was taken, and with the sun at a lower angle, the windows will not be fully protected and a degree of warming will be likely to the spaces behind, and which should be beneficial. This form of shading is extremely common in new European buildings, and this building could easily be mistaken for one designed for that part of the world. So it is both a sensible response to one of the environmental problems of the region, but disappointing in that it has no design component relating to the architecture of the region.

Earlier, and in tandem with the development of Hamad General Hospital – designed in 1973 and completed in 1980 – a programme for improving the Government’s response to primary health care was instituted in the mid-1970s with a small number of pilot centres being constructed around the peninsula. Based on the results of their operation, an initial six Primary Health Care centres were designed and constructed to take their place with the intent that lessons learned might be incorporated in those centres. The first six of these were opened in 1981, this example illustrating a typical setting with parking within its secured boundary, the entrance on the left.

As a result of the pilot schemes, the new designs were required to be flexible both from a management as well as a practice point of view, with amendments easily accommodated. The design of the six Primary Health Care centres was standardised and intended to minimise any specialised requirements that would be carried out in the new Hamad General hospital located to the west of Doha. Access to the centres was carefully segregated with sufficient space within their sites to accommodate vehicular access and parking.

The designed response created a flexible internal space with a clear spanning steel-framed roof supported on external walls. These were set at right angles to the perimeter of the building, the projections and overhanging roof giving a degree of protection from the solar loading on the relatively large windows. The roof contained all servicing in order to give flexibility in any future layouts, and was covered in a relaxing green stove-enamelled steel. While the buildings were modern in design and character, it is notable that the head of the openings in the plain walls and, perhaps, the angled walls below windows have resonance with traditional Qatari architecture.

Hospitals

The organised provision of medical services within the peninsula really began only after the Second World War. Prior to that there was a tradition of local medical treatments which were either carried out in private practices or by individuals offering traditional remedies. The latter was still common into the 1970s. Those needing treatment for more serious problems were obliged to travel abroad, either to nearby Arab states or to Iran or, if they were able to find the necessary resources, to Europe, particularly London.

In 1945, at the instigation of the Ruler, Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim, work began on the construction of a small twelve-bed hospital facing the West Bay, east of the Diwan al-Amiri with American funding associated with their presence in the developing oil economy. With the intent initially of catering for the more serious illnesses and diseases, the hospital later specialised in both orthopaedic and psychiatric cases, this work continuing into the 1970s with both professional and voluntary assistance from within the expatriate and national community and expanding from a single storey building to the two storeys shown on this photograph. By 1953 the hospital had fifteen in-patient beds, a rudimentary casualty room and a smaller room which served as the operating theatre. The hospital was known as the al-Jasra Hospital

But by 1947 the service provided by the hospital was being heavily used and it had become even more apparent that a modern, larger and well-equipped medical facility was now an imperative. Following requests and discussions a competition was organised in 1952 under the auspices of the Royal Institute of British Architects for a 120-bed hospital that would suit the country’s needs. Widely advertised, the hospital competition attracted hundreds of entries with the winning scheme determined to be that provided by John R. Harris. A perspective from the winning competition drawings is shown here.

However, before the new hospital could be constructed there was considerable pressure brought to bear, resulting in the expansion of the existing facilities with the construction of annexes housing four additional wards incorporating sixty extra beds, a kitchen, laundry, pharmacy, laboratory, X-ray, a physiotherapy unit and operating theatres.

The competition design was considered to be well suited to the novel environmental conditions in which the British architects were now working, though they had some experience of the region having been involved in an earlier project in Kuwait. The rooms were laid out on a double-loaded corridor system, were relatively deep and lit by light reflecting from the flanks of the projecting fins which were also designed to encourage through or cross-ventilation.

From both a conceptual and organisational point of view the design of the hospital was seen to meet the brief, to be well laid out and capable of working efficiently to fulfil the needs of the State. Note that the organisation of the plan of the hospital was wrapped around a central masjid.

The hospital was constructed on the west outskirts of Doha at Rumaillah, and became operational by 1957 with two hundred beds and an outpatient facility. Originally named the Qatar State Hospital, it was commonly known as the Rumaillah Hospital.

The aerial perspective above of the hospital competition scheme looks approximately south-west. This aerial view of the completed hospital, taken from the south-east in 1975, shows a little better the character of the façades of the ward wings. The buildings above it, a little left of centre, are the beginnings of some two-storey Government housing designed for Senior Staff, the road between them linking north to the Guest Palace and the fort.

This final aerial image was taken of the Rumailah hospital in 1975. Looking slightly west of south it shows the developments starting to spring up around the hospital. Running left to right at the top of the photograph is the road to Rayyan and, in the foreground is the Government’s Guest Palace with its green glazed tiled roofs. Left, just out of picture, was the British Embassy and Residence, much later taken down in order to complete the development of the hospital complex known as ‘Hamad Medical City’.

The first Women’s hospital in Doha was developed within the al-Jasra hospital site when it was possible to move patients from there to the Rumaillah hospital. Originally this contained forty beds for Obstetrics and Gynaecology. In 1959 this was moved to the Tuberculosis and Infectious Diseases Hospital and expanded to eighty beds then further expanded in 1965 with addition of some additional beds and a neo-natal unit. But it was evident that much more needed to be provided.

Planning for a Women’s hospital was begun at the end of the 1970s, with the project again designed by John R. Harris as a result of the State’s experience with the design and construction of Rumaillah hospital. It was eventually completed and opened by Sheikh Khalifa bin Hamad al-Thani on Independence Day 1988. Previously women had been treated at the old al-Jasra hospital following the moving of patients to the newly opened Rumaillah hospital.

Compared with the two-storey Rumaillah hospital, the Women’s hospital was designed as a single five-storey slab block sitting above a tall single-storey podium. The new hospital provided a total of 359 beds for women with 34 beds in the special Baby Care Unit. The rooms in the main block were provided with toilet and shower facilities with both single- and multiple-occupancy layouts. Served by three banks of lifts care was taken to enable a degree of flexibility for utility and service provision.

Like much of the construction in Qatar, the building was designed with reinforced concrete floors and columns, and with concrete blockwork infill both to internal and external walls. The construction elements were expressed externally both horizontally and vertically with the windows to the rooms being set back some distance both to reduce the effects of solar gain as well as to allow light to be reflected into the rooms.

The external effect of the cellular expressed structure was seen to connect with the traditional architecture of the peninsula, and a further small detail – the use of features that resemble maraazim, the traditional water spouts – also serves to reflect this relationship. Two much larger versions can be glimpsed on the right hand side of one of the photographs above.

While the medical facilities so far provided for the State were considered initially reasonable, by the mid-1970s the increasing population had begun to stretch the system. With the practice of Llewelyn-Davies Weeks Forestier-Walker and Bor working on the planning of the peninsula and Doha – and having a hospital specialist as one of their partners, John Weeks – a commission was given to design a new hospital intended to be the hub of the medical facilities in Qatar. Th design for Hamad hospital was approved in October 1973, work beginning on site a year later.

Some of the facilities on-site were running by the turn of the 1980s but the hospital was fully operational by February 1982.

more to be written…

Doha Tower

The examples illustrated above, together with others on these pages, show how some designers are taking advantage of the geometric character of traditional Islamic design to investigate solutions they hope are fitting for their purposes. In general these solutions produce designs that are based on screens arranged in a geometric pattern. Perhaps the best known of these is the screen wall at Jean Nouvel’s Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris where the geometry is formed of mobile devices that diminish the apertures they form with the increase in sunlight falling on them.

This example in the NDOD appears to be a more simple arrangement than that, but is interesting from the point of view of analysis. It is essentially an external brise soleil screen based on eight point geometry, a common construction in Islamic designs. Away from the enclosed building, a basic screen has been constructed of octagons joined by the smaller squares needed to make up the spacing between them. In this series of illustrations it can be seen how the screen is then supplemented with two progressively smaller scales of screen to produce a three-dimensional screen whose smallest octagon appears to be around thirty centimetres. It will be interesting to see how the device is detailed in order to minimise glare from reflection. What is particularly notable with devices such as this is that the design is fixed, whereas the sun traces a path around the building requiring, in theory, varying design responses on the building’s different aspects, and differing through the year. Here the response has been to vary the aluminium mushrabiya to provide different degrees of protection from the sun with 25% to the north, 40% to the south and 60% to the east and west from where the higher solar loading is likely to be experienced.

Between the external geometric screens and the building’s glazed façade there is a maintenance walkway on which are located the lighting elements creating the strong presence the building presents at night. This gives good and safe access for the cleaning of the windows and other maintenance tasks. Generally the lighting of façades is made from the outside of buildings by virtue of there rarely being a double skin, as in this case. This has the usual disadvantage of creating glare on the glass, reducing the ability to see clearly through the glass by users of the building at night. However, the locating of the lighting system between the two façades of screen and glass illuminates the inside of the screen when viewed from the inside of the building. While this creates a very strong wallpaper pattern for users of the building at night, it is likely to diminish the ability to see and experience the magnificent views to be obtained across the West Bay by virtue of glare from the screen. This may also be compromised by condensation which can be seen on the glass to the right of the photograph.

Qatar National Museum

In the early 1970s the Ruler at that time, Sheikh Ahmed bin Ali al-Thani, decided to ensure that the abandoned development standing at feriq al-Salata, the residence and office of his grandfather, the late Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim al-Thani, should be refurbished and retained as an important element in the physical history of the peninsula. At the same time an addition would be made to it in order to bring together and display important objects relating to the historical context and emergence of the relatively new State.