a collection of notes on areas of personal interest

- Introduction

- Arabic / Islamic design

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 01

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 02

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 03

- Arabic / Islamic geometry 04

- Islamic architecture

- Islamic urban design 01

- Islamic urban design 02

- Islamic urban design 03

- Islamic urban design 04

- Islamic urban design 05

- Arabic / Islamic gardens

- Gulf architecture 01

- Gulf architecture 02

- Gulf architecture 03

- Gulf architecture 04

- Gulf architecture 05

- Gulf architecture 06

- Gulf architecture 07

- Gulf architecture 08

- Infrastructure development

- The building industry

- Environmental control

- Perception

- The household on its lot

- A new approach – conceptual

- A new approach – principles

- A new approach – details

- Al Salata al jadida

- Public housing

- Expatriate housing study

- Apartment housing

- Pressures for change

- The State’s administration

- Society 01

- Society 02

- Society 03

- Society 04

- Society 05

- Society 06

- History of the peninsula

- Geography

- Planning 01

- Planning 02

- Population

- Traditional boats

- Boat types

- Old Qatar 01

- Old Qatar 02

- Security

- Protection

- Design brief

- Design elements

- Building regulations

- Glossary

- Glossary addendum

- References

- References addendum

- Links to other sites

Issues of note in the region

A number of factors contribute to the pressures for change within Qatari society. They reflect, in the main, emerging difficulties common to many of the Arab States as well as developing socio-psychological issues. Most of the pressures are seen by Arab commentators to stem from interference by the West in Arab affairs, a misunderstanding in the West of Islam, and by an endemic conflict between modern Arab moraes – usually developed through contact with the West – and the life thought to be prescribed by the Quran. Within the Arab world there has always been a lively social debate carried out through the medium of the written and spoken word, a tradition which, during the Arab renaissance, produced many works of beauty and relevance in parallel with the advances in the sciences. Nowadays this debate is being seriously constrained by a number of individuals and organisations who are perceived to be repressing the free expression of social debate – particularly that of the printed word. Some writers now claim that the issues of religion, sex and politics are dangerous areas in which to express opinions.

Although it is generally argued that the West is responsible for a variety of problems, where this blame rests is difficult to pinpoint. There is the difficulty of comprehending the cultural background of the region both in the West as well as in the Gulf. It is a platitude that, at a general level, modernity appears to be equated with the close resemblance of habits, practices and institutions similar to those of the West: in other words, modernisation is synonymous with Westernisation. Observation suggests that younger generations do not have the same attitude to traditional values as their parents; and even the parents share the dilemma of how to benefit without losing their cultural values or, more important, how to deal with change while retaining those values. It is not clear how far this is generally understood, nor how those that govern the States understand the difficulties intrinsic in replicating Western institutions; though they are certainly aware of it. Many Muslims are aware of the dichotomy produced by development even if only from a reactive point of view; hence the rise of fundamentalism. In this reactive development lies the seeds of global conflict, this time a probable conflict between civilisations.

It is commonly thought by Western as well as Muslim architects – and others – trained in the West that new development is an improvement on old development. The theory seems to be that change is associated mainly with two factors: movement to towns and the introduction of air-conditioning. For instance Geoffrey King, an architectural commentator who I’ve quoted here, believes that:

…the adaptation is by no means perfect aesthetically – in that respect, traditional architecture was far more pleasing. Yet in the modern concrete building people are comfortably housed in terms that meet Saudi Arabia’s social and religious traditions and in accord with perceptions of an Islamic lifestyle. Women still retain privacy and houses are designed to achieve this: there is often a separate entrance for women and the men’s majlis is organised so that it gives no views into other parts of the house to the male visitor’.

Even though this quote relates to Saudi Arabia, the State’s traditional connections to its adjacent, littoral Gulf States suggests that the argument might apply similarly to Qatar. Yet new development in Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States – contrary to King’s assertion – does not fulfil, in anything like a similar manner, the precepts of the older developments, nor are the buildings more effective in successfully containing the new social operations.

Change in this context is difficult to define as it means different things to different groups. Here it is taken to be a conscious desire to change from the old values to something else. From a Western perspective we tend to see change in the Gulf as a movement towards Western values and, perhaps a benefit to the peoples of the region. To some Arabs this is undoubtedly the case. Though to a majority change is certainly seen to be happening, but the influence of the West is heavily resented, representing as it does all that is seen to be harmful to a search for pan-arabism and, particularly, for a post-colonial identity free of the colonisers – the West in general, and the United States in particular.

Certainly many Arabs have taken an interest in the West and the tools by which the West has achieved its present status, but they are more than matched by those who believe there should be a return to the original Islamic values. The former were epitomised by the Egyptian writer and thinker Taha Hussein who believed that the Arabs should master European culture in order to progress themselves. The majority, epitomised by his contemporary, Hasan Al Banna – founder in 1926 of the militant Muslim Brotherhood – argued that, on the contrary, Arabs should reject such contacts and return to the pristine Islam that was the setting from which sprang their great and heroic past.

The interests of the West in the area involved measures that were unpopular both within the West and in the Arab countries affected by colonial interests. As is described elsewhere, many of the countries of the region in fact owe their present boundaries to the involvement and requirements of the West – particularly of Britain and France, and this basic focus for resentment has enabled many Arabs to concentrate their disquiet against the West. However, the West not only established the boundaries of the countries of the region, but they were also responsible for setting the tone of the administrations that would run the newly defined countries. To some extent they had a choice, but it was realised that there would be considerable difficulties if a radical approach was taken and an effort made to introduce democratic institutions and administrations together with the outlooks that would make them realistic and workable. Rather than set about this impossible task the West established boundaries and attempted to reinforce the existing system of tribal government setting the seeds for many of the problems that have emerged in the region today. The system whereby the strong take charge and hold power by force does not produce the democracies that the West would like to see in place.

The overriding problem here is the inability of the West to understand the basic concept of Islam and the way in which Muslims differ from – for the most part – Christians in the West in many of their conceptual and behavioural attitudes.

Essentially, it is imperative for the West to understand that Islam subjugates the person to the community – not in a pejorative sense, but as an essential characteristic of the religion – and it has to be borne in mind that Islam is a social code in complete contradistinction to Christianity. In Islam, the concepts ‘self’, ‘community,’ ‘brotherhood’ and ‘nation’ have very different meanings from our understanding of those words in the West. Jonathon Raban points out that the subjective self found in the West is conceptually alien to the manner in which individuals in Islam see themselves. He points out that Muslims define themselves not by the understanding of their inner thoughts and conceptualisations, but in their interaction with others in their society. He quotes Rosen, noting that:

the configuration of one’s bonds of obligation define who a person is… the self is not an artefact of interior construction but an unavoidably public act’.

To understand the manner in which Muslims behave in both their public and private physical realms, this relationship of the person to the society has to be understood in its complexity – and in its simplicity. Raban has a very strong metaphor of its strength:

The idea of the body is central here. On the website of Khilafah.com, a London-based magazine, Yusuf Patel writes: ‘The Islamic ummah is manifesting her deep feeling for a part of her body, which is in the process of being severed.’ It would be a great mistake to read this as mere metaphor or rhetorical flourish. Ummah is sometimes defined as the community, sometimes the nation, sometimes the body of Muslim believers around the globe, and it has a physical reality, without parallel in any other religion, that is nowhere better expressed than in the five daily times of prayer.

The observant believer turns to the Ka’aba in Mecca, which houses the great black meteorite said to be the remnant of the shrine given to Abraham by the angel Gabreel, and prostrates himself before Allah at fajr (sunrise), dthuhr (noon), asr (mid-afternoon), maghrab (sunset) and isha (night). These times are calculated to the nearest minute, according to the believer’s longitude and latitude, with the same astronomical precision required for sextant-navigation. Note that the crescent moon is the symbol of Islam for good reason: the Islamic calendar, with its dates for events like the hajj and ramadhan, is lunar, not solar. Prayer times are published in local newspapers and can be found online, and for believers far from the nearest masjid, an inexpensive adhaan clock can be programmed to do the job of the muwadhin. So, as the world turns, the entire ummah goes down on its knees in a never-ending wave of synchronised prayer, and the believers can be seen as the moving parts of a universal Islamic chronometer.

Muslims are very conscious of this continuum and of their relationship with other Muslims, not only those they know but also those at the other side of the world; they have an innate awareness of ummah. Although Jews and Christians are considered to be ‘people of the Book’ – a reference to their appearance in the Bible – Muslims know, absolutely, the primacy of their true religion and its governance over their lives.

Decisions, decisions…

One social factor stands out from the rest, and that is the manner in which the society is responding to change. Traditional Gulf societies are formed on a feudal principle of primus inter pares – first among equals. Families assume an order of precedence, and those within a family are similarly ordered. Decisions are based on shared values, traditional allegiances, religious requirements or guidance, and political judgement. The society is not pluralist and depends to a large extent upon its received history – usually a function of the older members of the families to record, process and pass on when and as needed.

Today the structures of government which have been adopted from the West conflict with the traditional ways of making decisions. The majlis system is conceptually different from Western systems which bring together, for example, ministers to decide on their requirements. In particular government establishes another power base – differently structured from the majlis system – which an individual would normally be anticipated to organise to his own advantage. Although this follows the established system rewarding faithful and successful supporters of a leader, there is considerable room for misunderstanding. In the past those who had been rewarded were permitted to operate with some degree of impunity, provided that the leader was not embarrassed and continued to receive what was required. The new systems of government require more openness, inspection and, particularly, integration. In many ways these are inimical to the traditional system of government and are the cause of much misunderstanding and resentment.

The fact that these systems are supposed to be similar to the democratic models of the West reflects both the West’s requirements that others organise themselves as they do, as well as the desire by some elements of Arab society to take Western models as a way of developing their own interests, a trend which suggests an interest in control and management as a normal political function.

This system has been buttressed by the considerable natural resources available to the State, resources which set Qatar apart from its fellow emirates. But pressures are being brought to bear on all the region, particularly by the International Monetary Fund who wish to see increased financial restraint within the area generally, married to considerable political reform in order to safeguard the future stability of the region.

In order to respond to this, Qatar is attempting to develop the private sector and reduce the dependence of its national population on the State. But it is difficult. Saudi Arabia has been accused of buying off its young nationals in the wake of the Arab Spring developments, and this route has been seen by the State as being problematic. Instead, Qatar is focussing on its Qatar National Vision 2030 which is intended to reflect the aspirations of all Qataris, not just Qatar’s leadership. This initiative aims to create a State capable of sustaining its own development while retaining its traditional culture. This is a difficult strategy to follow as the cultural base is being swamped with Western influence. Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa has been quoted as saying:

A new era begins in the Arab world from the ocean to the Gulf. Qatar, which looks forward to the future and which is always developing, is reconciled with itself and with its values and is in harmony in its march with the movement of history towards a better future and the interests of the community and the Qatari citizen remain at the top of our priorities and concerns.

It is intended that the State will ensure that Qataris will not develop a sense of entitlement but of inclusion, playing their part in decision making through a variety of methods including universal suffrage. This is similar in some respects to the traditional majlis system, but is considerably different.

Statistics and external pressures

The pressures acting on and within the society are now immense. Increasingly references are being made to unfortunate results of the intensive development with external commentators finding little being done to ameliorate the problems they note. The rising number of divorces, diabetes and related health problems, kafaala and the workforce, the unsettled feelings of Qataris – all these and more are being aired publicly with a variety of reasons suggested for their incidence and character. But many of these views or criticism are very commonly formed from Western perspectives and may not tell the full story of how change is affecting Qataris. Even work in the Ministries and University may similarly not focus on the areas which will identify the problems and, through that, develop means for correcting or at least ameliorating their impact.

Government organisation within Qatar have long had a propensity to collect statistics to an unusual degree of detail. The intention is good and it is believed that their study will enable policies to be adopted that will benefit Qatari society:

Indicators derived out of these data reveal all aspects surrounding the marriage and divorce phenomena, which gain great interest in the field of population and social studies.

The demographic behaviour of the society, in general, can be identified through analysis of marriage and divorce statistics. The indicators provided by the statistics of marriage and divorce can be used as a benchmark for achieving short and long term goals to improve social conditions for all members of the Qatari society.

At its simplest, concern is being expressed for statistics illustrating that, inter alia, fewer Qataris are marrying, a fifth of marriages are over before consummation – though there is ambiguity in the manner in which divorce statistics are recorded – the conflicting expectations and behaviour of couples, a significant disparity in education attainment, the rising costs of marriage…

While the collection of data can be of great value, it places considerable onus on how that data is then interrogated, goals, objectives and policies developed, and actions formulated and executed. Of particular concern should be the avoidance of pre-judging what the data might be thought to illustrate, yet this seems to be an area where Western intervention creates misinterpretation and where the publication of random statistics can mislead.

Reading the questions set out in questionnaires and reports dealing with Qataris in employment, it is noticeable that they tend to follow international views relating to work and behaviour suggesting a desire for Qatar to simulate Western countries. The studies appear to have little insight from a Qatari socio-cultural viewpoint. Whether this is because they do not understand the issues, or whether they have chosen to ignore behavioural patterns is not clear, but whatever the reason might be, it must put their conclusions in doubt.

For instance, the latter report states that ‘in most countries, around 8% of the working population have to be executive and senior leaders’ and that, by extension, 120,000 Qataris will be needed to fulfil leadership roles – this figure being 8% of the 1.5 million working population, then noting that there are around 150,000 employable Qataris, reasoning that up to 80% of this number will need to be leaders.

The Government statistics of the last quarter of 2013 state that the working age population of Qataris was around 181,000, while conceding that the active labour force was 96,000 of whom male Qataris accounted for 67% of this figure.

It seems unclear as to where the figure of 150,000 employable Qataris comes from as, in 2009, there were 96,224 Qatari men and women actively employed in the workforce with another 84,387 inactive – the latter being mainly homemakers and students. This appears to show a drop in the numbers of actively employed Qataris between 2009 and 2013.

But there is no reason to believe that Qatar should have a leadership cadre of 8% particularly bearing in mind a number of aspects which suggest it is not like many other countries. Its extraordinarily rapid pace of development, the character of its administrative structures, the regional and international political relationships, educational issues, socio-cultural traditions and religious pressures are some of the areas which seem to have been ignored in suggesting this similarity.

If it is to mimic other countries in the distribution and character of its leadership organisation, then this is likely to come about with the dislocation of its socio-cultural structures with their significant tribal and religious components. There are already worries noted for the difficulties Qataris face with the development of their country, and these may well herald greater concerns for a loss of identity.

In physical terms there is little left in Doha that those living there a generation ago would recognise. The Diwan al-Amiri and Sheraton would be two prominent structures with, perhaps suq Waqf – though this has been re-built – but nearly everything else is new. In this reconstruction, the physical and social linkages that families enjoyed have been arbitrarily redistributed with Qataris now a significant minority in their own country. With the best will in the world, it is not easy for them.

Efforts are now being made to find and encapsulate in a variety of forms, something of the past. The collection of these resources appear to have been formulated both to record and remember the past as well as encourage tourism. A number of institutions have been established and generally tasked with finding and preserving what remains of the heritage within the peninsula. This applies not only to archaeological work such as that which is uncovering the history of the north-west of the peninsula, but also to the recording of socio-cultural aspects of Qatar. In addition to this buildings are being refurbished and, in the case of suq Waqf, reconstructed, a subject which has been noted on other pages of these notes with regard to its design and its operation as a touristic feature.

more to be written…

Religious

There are strong populist demands for change within the region. Bahrain, for instance, is under pressure from within its strong shi’ite community, and this has been reflected in the closing of the National Assembly, continuing unrest on the streets, the arrest of many considered to be potential trouble to the State and the expulsion of others in defiance of United Nations policies. Recent voting – late 2006 – has seen a radical shi’ite group gaining sixteen of the forty seats in parliament with the concomitant expressions of concern for what might now happen in Bahrain. However, power resides with the ruling family and the appointed Shura Council, and it is these bodies which must agree any legislation promulgated by the elected parliament. While there are strong arguments for drawing the different religious factions together under a national initiative, the history of the region – as well as of the religious groups, of course – does not appear to hold out much hope for this. And this will affect the attitudes of the neighbouring States that have sunni majorities.

The United Arab Emirates, who also have strong commercial links between their shi’ite nationals and Iran, have similar problems. Kuwait has been pressured not only from the same source – shi’ite have generally been assimilated into the Kuwait society in contradistinction to northern Arabs such as Palestinians and Iraqis – but also by issues relating to the role of women and non-Kuwaitis. Since the invasion there is some degree of normalcy returning to Kuwait – to the extent that an evening programme in English has been started, catering for lovesick Kuwaiti youth. It is noteworthy that the station manager told Reuters ‘We forget we’re in Kuwait. We think we’re in the US or Europe. The station has opened the door and taken people outside.’

Qatar appears to be holding its own mainly sunni population together but complaints caused by reduced income and constraints on liquidity are likely to increase the interests of some in moving the country towards fundamentalism, and this traditionally results in attempts to constrain the more visible aspects of non-Islamic religions and women.

Since the assumption of power by Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa from his father in 1995 there has been concern expressed by neighbouring States – particularly Saudi Arabia – for his radical policies which are making them increasingly worried. Not only has he stopped media censorship, but he talks to the press, has spoken positively of democratisation, an idea that has traditionally caused problems for both Bahrain and Kuwait, has held municipal elections and appointed a woman to a ministerial role. In addition he has sought better relations with both Iran and Iraq and, even with Israel in regard to an important gas deal.

At the end of the twentieth century there was particular concern being discussed in the majalis of the Gulf that the West would introduce another shi’ite state at the head of the Gulf. Protection below the thirty-second parallel was thought to be a prelude to an attempt to split Iraq into three parts – crudely this would see Kurds who hold the majority in the north, sunni in the centre, and the shi’ite in the south of the country. There is a considerable history of mistrust and worse in the Gulf between sunni and shi’ite and any consideration of the latter being assisted to establish themselves more formally on the Gulf is resented because of the perceived links they have with Iran.

It will take a considerable time for the problems associated with the West’s initiative to depose Sadam Hussein to work themselves out. Some believe the whole area to be now far more unstable than it was and, mirroring the difficulties to be seen in Afghanistan, there will be extensive manoeuvrings as tribal leaders, powerful individuals and those who wish to become more powerful and, particularly, religious leaders struggle to sort out national and religious boundaries, most of them legacies of the West’s involvement in ‘settling’ the area at the beginning of the twentieth century. The extent of demands for the creation of Islamic States should not be underestimated because such States incorporate the power of Islam in its insistence upon a just society based on the Holy Quran.

Fundamentalism – a movement to return to the fundamental values embodied in the Holy Quran – is found throughout the Muslim world and is one of the strongest factors now perceived by the Arabs to affect them. Fundamentalism appears to some in the Arab world not to be a desire to return to the purity of religion as a means of benefiting the society, but as an end in itself. Prominent speakers have equated it with fascism and claim it can only be stopped by the same methods it uses: violence.

It is not my intention to discuss fundamentalism here but, for those who have not thought about it and its effect on the Gulf and Arab world – if not the West – it might be useful to note some of the simplistic and common arguments given for its rise. These perceptions include, but may not be limited to, and in no particular order:

- the repression of traditional tribal leadership systems and structures,

- discrimination against traditional life styles,

- the accumulation of wealth by a limited number of individuals, and

- the interference by the West with the intent to support Western-inclined leaders and maintain poverty and dependency.

In the area around the Gulf this latter is seen very much as the West interfering solely due to its need for oil and gas.

Fundamentalists see the resolution of these issues as being resolved in the creation of an Islamic state, one where shari’a law governs the state and religious leaders, in their interpretation of shari’a, essentially govern the state.

From time to time fundamentalists make themselves known through their public activities. There have been reports not just of activities being disrupted but of more violent attacks in Saudi Arabia and, even, Qatar.

The home of the Holy Quran and the backbone of the Gulf States, Saudi Arabia, continues to be pressured by fundamentalism. In February 1992 the King announced constitutional reforms designed to go some way to warding off criticism over secular excesses. A consultative council of sixty citizens – majlis al shura – will be able to initiate legislation and review foreign and domestic policies. However, it took until August 1993 for the members of the majlis to be named. Prior to this the King generally acted in close co-operation with the ulema, the country’s supreme religious authority. Concern for the zeal of their police, the mutawain, has led to the introduction of new laws giving the individual more rights at the expense of the mutawain. It is likely that the changes in Saudi Arabia will be mirrored both by pressures within the Gulf as well as by similar responses.

Saudi Arabia and other Muslim States are unsure how they should deal with fundamentalism which attacks them at their most weakest point: their alliance with the West. In addition King Abdullah, as King Fahd before him, continues to resist pressures from the West for democratisation. It is apparent that, in stating that his society – and those of the Gulf – are not and can not be based on western-style democratic model he is attempting to resist the arguments not only of the West but of the religious fundamentalists and their requirement of a closer reading and interpretation of the Holy Quran.

The Saudi Arabian royal family continue to have difficulties with their right to rule the people of Saudi Arabia founded as it is in their claim to be the proper leaders of an Islamic society. Difficulties with the delicate balance between the family and the Council of Senior Ulema – the highest religious body – serve to further antagonise the fundamentalists who increasingly attack the government and royal family for profligacy and corruption. More than this there is now serious anxiety in the West for their alliance with the King. There is a concern within Saudi Arabia that the royal family are out of touch with their support and the consequent move towards fundamentalism can be construed as a move towards the strict wahhabi roots of the Kingdom. Perhaps, more importantly, there is considerable concern within and outside Saudi that the public finances are seriously depleted. To a large extent the State depends upon the people for support and, in this regard, the degree to which the State benefits its people is a factor in their continuing support. If this benefit falters or is perceived to be no longer generous, and if this position is seen to be due to a fault in the leadership, then there is likely to be immediate and evident grounds for dissent. Failing the ability of the traditional society to deal with this – as in the past, perhaps by the use of loyal badu troops – there is likely to be dramatic change. Leading intellectual and religious wahhabi have formed a focus for disagreement, and the formation of a Human Rights group and the immediate arrest of its leaders is seen by the West as the most serious demonstration of a lack of clarity of vision for the future of the Kingdom.

Kuwait suffered from the invasion by her neighbour, having her national aspirations for Arab nationalism and Islamic identity thwarted and the conditions for Westernisation seeded. The elections held in Kuwait caused alarm throughout the Gulf as many see the dangers they foresaw now made apparent. The previous twenty-one member Cabinet was replaced by sixteen ministers appointed by the Emir, including three Islamists, and the parliament has the power to force ministers to resign. Bearing in mind the Government were roundly defeated in the elections – Government having thirteen seats in the fifty man parliament – this is likely to exacerbate friction between the Royal Family and the merchant families who are heavily represented in the parliament. It is of note that the Kuwait Islamic Movement has eighteen deputies affiliated to it. More recently women have been voting in, and voted for, in the Kuwait parliament. This has sent tremors not just through Kuwait, but through the Gulf.

Of greater note, the autumn of 2011 saw a dramatic change in the conservative Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Women are to be allowed, not just to stand as candidates in Municipal elections, but also to vote in them though they will be unable to take up their suffrage until 2015. It is an interesting development in the region and follows considerable debate within the country on the rôle of women within the framework of the strict variety of Islam practised there. Three issues have dominated that debate – women not being permitted to drive; their need to be accompanied by a male relative when outside their house, particularly outside the country and permission being needed for them to undergo operations; and their inability to vote. Now they can both vote and stand as candidates, though this in itself may create additional problems by a more articulate and representative majlis al-shura.

Already within the Kingdom there are those who believe the Municipal councils have little power incorporated within them. Only half the seats are open to the male electorate, the other half being government appointed. How the new councils will be structured is not yet understood, but opening the issue of the councils’ effectiveness to a wider electorate may well increase the criticism they face. Commentators believe that women’s suffrage has been forced against the interests of both a number of clerics and members of the ruling family, and in the hope that this will reduce some of the internal tensions within the country, a number of concessions having been made earlier in the year.

The point is that these issues, in varying degrees, are common through the Gulf and changes in the status quoin any country are viewed and aired in the majaalis in their wider and narrower contexts. Emancipation can bring both enlightenment and conflict, particularly at a time when there is thought to be considerable turmoil in the Arab world.

The pressures for change in the Gulf are, from the Western point of view, conservative and appear to require the society to return to a more traditional status. At the same time Western observers note that there is a strong argument that those who direct opinion towards a conservative society, do not themselves have the experience of the West and its beneficial aspects, and are inclined to a prejudiced view of the West and its impact upon the Arabs. With an implicit belief in the quran, of course, there is no need to have experience of the West.

It is imperative to bear in mind at all times that Arabs generally, and Gulf Arabs in particular, are as conscious of their Arabism as they are of their religion, and that this affects their attitudes to everything they do or think about – particularly their view of themselves within the ulema. It is not a question of choice; they have been brought up to follow the directives and traditions of the quran.

Moving a country forward in the Gulf is not easy. Commentators have pointed out that Sheikh Hamad is having to move carefully, particularly as he is at the forefront within the region in seeing through changes that will align it more with the democratic West. Because Qatar is conservative and tribal by nature, the argument is that changes are more likely to succeed when institutions have been introduced and a more liberal political and social environment exists. To this end 2004 saw a law to enable professional societies, a human rights group now exists, women are also now allowed to organise themselves and, as I have noted in number of places, the opportunities for education have dramatically improved for all. As you might expect, there is a rearguard action being fought against what is seen to be liberal or, even, irreligious changes to the status quo. In 1997, a University professor was jailed for three months for opposing the franchise of women and, in 1998 a petition was presented to the Advisory Council complaining about the reforms, particularly those that might see women gaining some dominance over men. The problem of changes also saw a number of bedu tribesmen expelled in 2005. The significance of the latter is that this particular tribe has links throughout the region.

In 1999 Sheikh Hamad presided over the first elections in Qatar’s history for the twenty-nine seats of the people’s Municipal Council. Although a larger number initially registered, two hundred and forty-eight candidates, including six women, eventually stood for the seats. 21,995 voters registered to vote, this being considered relatively low for a number of reasons. None of the women won a seat.

I should point out that there are a number of different, and apparently official, figures that conflict. The figures in these few paragraphs are my best interpretation. It is important to note that the numbers of people who register to vote appear to be significantly higher than those who actually vote, and that the numbers who register to vote are not a large proportion of the Qatari population.

In 2003 the second elections for the Municipal Council saw twenty-five members elected from eighty-eight candidates, and and additional four, including a woman, elected unopposed. ‘Nearly 40% of the total voters of 21,024 exercised their franchise,’ this being down from 55% in 1999.

As is true in most countries, not everybody can vote. The conditions for voting, and for standing in elections, are that a voter must:

- be Qatari or, if granted Qatari citizenship, this must have been given at least fifteen years previously,

- he or she must be at least eighteen years old,

- not have been convicted of a dishonorable crime or a crime of dishonesty, unless he or she has been rehabilitated,

- should be a resident of the electoral constituency in which he or she will exercise their electoral rights, and

- should not be employed in the armed forces or police or, I believe, the Ministry of the Interior.

The next election year, 2007, saw the number of eligible Qataris registering to vote rising to 28,153, but only 51% actually voting. There were 116 candidates running for a seat on the Council, of whom three were women. Again, one woman was elected, Shaikha Yusef Hassan Al Jufairi defeating two male opponents and winning 90% of the vote in the Old Airport district. It was she who, in 2003, became the first woman to be elected, unopposed, to the Municipal Council.

This body, together with the Advisory Council – the thirty-five members of which are appointed by Sheikh Hamad on a four-year basis – serve to advise him. The latter body is made up of prominent landowners, farmers and businessmen and, although they have no legislative powers, are influential. These two bodies are, in effect, a formalising of the majlis system, the traditional mechanism for dissemination, discussion, direction and decision-making.

Generally, trends of change illustrate a conservative bias with a number of voters stating that they would vote in line with tribal connections, and preferring men to women. However, the wife of Sheikh Hamad, Sheikha Mosa, enjoys a high profile and has advanced both education and the rights of women in Qatar. While this might not be popular with traditional society it is, nevertheless, an extremely important initiative bearing in mind that Sheikha Mosa is not a member of the Ruling Family by birth.

Some other issues

While there are a large number of issues that should be understood in considering the population of the country, a specific one to note is the preponderance of non-Qataris in Qatar. Around an eighth of the population is Qatari. A large proportion of these Qataris are young, and even though Qatari women are increasingly seen outside their homes, male Qataris carry out their private and public duties in relative privacy. These are, perhaps, some of the reasons why foreigners believe that the proportion of Qataris to non-Qataris is even lower than it is.

Issues such as this are now relatively freely discussed as the present Ruler and his wife have introduced the beginnings of many democratic principles, doing away with the Ministry of Information, abolishing censorship and introducing Al Jazeera, the television station that has changed the perceptions of many round the world by their broadcasting news and issues that were not previously seen in the West. While these may seem to be positive introductions, they have created unease in some parts of the Arab world, if not elsewhere.

With a significant minority of nationals, expatriates are drawn to Qatar in order to work and receive benefits they would not be able to obtain in their home countries in a reasonable time frame, or at all. Generally they stay in the country only a few years before returning home with their savings. Because of the need to save, expatriates are relatively well-behaved and take no part in the political operation of the country.

However, the changes that are taking place in the peninsula reflect a pattern operating through the Gulf and the Arabian peninsula. Two of the factors to be borne in mind are the large financial resources underlying the different states, together with their uneven distribution. At its simplest, Bahrein, Dubai and Oman have the least of these resources and are not able make provision for their futures in the same ways in which Qatar, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia can, particularly with their foreign investments.

The manner in which the wealth of these countries is being disbursed also affects the way in which their societies develop. These states can be described as rentier states, ones where their citizens derive wealth from the largesse of government, not by their own productive efforts. It follows that citizenship is a source of economic benefit. Certainly, effort is required to create personal wealth, but it is facilitated by the state supplying resources. For instance, land is made available to Qataris, together with interest-free loans for development. Education and health care are free. Public sector employment is available with good salaries, pensions and amenable conditions. Above all, there is no personal income tax applied. It is argued that these and other provisions and benefits create a situation where political participation by citizens is diminished and where nationals come to represent a social elite.

The legal framework in Qatar

As has been described in more detail on the history page, on the 3rd September 1971 Qatar declared itself independent from British protection. Prior to this date the British had administered justice over the non-Muslim population of the peninsula, the Muslim population being subject to Islamic law applied by the shar’ia court. With independence a new court structure was introduced, the ’adliya or Civil court, in effect establishing a dual system of law which differs from the other Gulf States as well as Saudi Arabia.

While Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrein also have dynastic Rulers, they differ from Qatar in that the affairs of non-Muslims are regulated there by courts or committees whose jurisdictions are governed by their respective Rulers and Councils of Ministers. In Qatar, by contrast the ’adliya court is independent, enacting its own legislation, this being supervised but not effected by the Minister of Justice, as in the other States.

Traditionally justice in the peninsula was administered by the heads of the tribes that made up the badu populations that ranged in and out of the peninsula, though with some degree of settlement. This followed a strict code of application based on tradition and precedent known, unofficially, as ‘tribal’ or ‘desert law’.

The nineteenth century saw the developing importance of shar’ia based on the Holy quran for both its sources and rules. The important distinction to note is that there is no difference between civil and religious obligations which are emphasised in preference to any personal rights a person might be thought to enjoy. This development was carried from Saudi Arabia into Qatar with the growing influence of wahhabism and its adherence by the main tribes there. The Ottoman empire had been actively establishing itself in the region for centuries and, during the nineteenth century witnessed a degree of settlement in the peninsula that was buttressed by shar’ia law. Disputes were settled now under the shar’ia, but with the right of appeal to the Ruler. The importance of this was that many of the traditional ‘desert laws’ were now either subsumed within the shar’ia or were outlawed by it.

The treaty with the British of the 3rd November 1916 saw the introduction of British legal institutions governing British and non-Muslim residents of Qatar, while shar’ia continued to be the law governing Muslims. The British legal system had its principles based on Common Law, legal representatives were permitted in court and appeal was to the Privy Court in London.

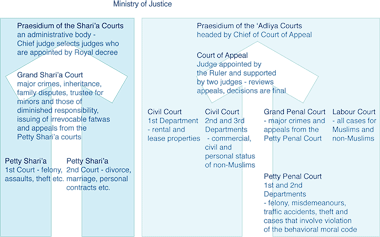

But, as mentioned in the first paragraph, the changes being brought about by the increasing contacts with the West, due to the rapidly expanding development of the peninsula’s oil resources, saw the introduction of ’adliya courts in 1971. These were intended to run in parallel with the shar’ia law and courts which were now finding it increasingly difficult to deal with many of the issues arising from the modernisation of the State. This diagram, illustrating the dual system, has been developed from that given in the article used to write much of this background note.

In order to practise, judges in the shar’ia courts are required to have a degree in shar’ia studies from an Islamic school, usually from Saudi Arabia or the al-Azhar university in Cairo. By contrast, judges in the ’adliya courts must have degrees from the law school of an accredited university and have practised for a prescribed number of years. In this they represent the two different characters of shar’ia and ’adliya: essentially the application of the word of God, and the rules of conduct based on a developed notion of justice, respectively.

The development of legal systems designed to respond to modernisation is argued to be marginalising the shar’ia law and its courts, perhaps even to restricting its role to family law. The most notable ramification of this trend is the increasing separation between religious duties and civil obligations which, according to shar’ia law, are indivisible.

This trend has seen ramifications in two areas which might be thought to create pressures within the country. The first is in the rise in the number of judges, lawyers and trained personnel operating within the ’adliya system. They outnumber those operating in the traditional, shar’ia system, but also operate increasingly through moraes developed from the West which are naturally in conflict with traditional values. They represent the basis for a different character and, perhaps, socio-cultural grouping from their counterparts brought up and working in the traditional, shar’ia systems.

The second area is that related to Islamic fundamentalism. As the judges of the shar’ia court are government appointees it is considered that they are more likely to support the conservative establishment while being more resistant to the character and ramifications of modern law. By extension it can be argued that modern legal systems are inimical to fundamentalism and that this will be witnessed, in their thinking and behaviour, by those most distanced by modern development, the badu and those households in the least urban settlements.

Family relationships

With the increase in wealth, the purchase of land by the Government to benefit the Qataris, and their re-housing in estates, the close physical links between family members have become stretched. Upward mobility, education and the dramatic changes of the last twenty years have resulted in life styles that have stressed the strong, traditional family links, creating a range of problems, many of a character than have not been previously experienced and some that are not widely recognised. Material benefit is not a problem in itself, but the manner in which it is handled in a Muslim society can be problematic.

Perhaps education is the area in which this is readily seen. It is not at all suggested that education, discussed below is wrong, but it is the factor which may have created the most dramatic change. Many men now have work outside the house and children are schooled from an early age through tertiary education, both boys and girls. The hours of work and education do not coincide, creating organisational difficulties within households and, with children receiving an education which was not available for many of their parents, it is not surprising that there are the possibilities for conflict and alienation within families. This is reinforced by the opportunities for consumption, particularly those associated with recreation outside the house. However, Islam is a strong binding force and, although many of the pressures run against its general and specific premises, the socio-cultural history of the State is considered by Qataris to be strong enough to resist the worst excesses of change.

One of the most serious causes of alienation is likely to be the movement of families away from the traditional extended pattern towards nuclear families. As young men and women move through higher education and marry, the State will provide them with land and a house, a serious inducement to establishing a nuclear family compared with continuing to live with parents and relations within the traditional, extended family pattern on a single or adjacent residential sites.

But this is not always the case. It is possible that nuclear and extended families might live together, either the new, nuclear family living within the nuclear family or, with the advantage of new housing, the extended family living with the nuclear family.

The nuclear family is characterised by increased economic or financial independence and, as such, has a different relationship with those in the extended family. The latter, with its integration of three or even four generations has inbuilt within it a series of values that are passed on and shared with regard to education, behaviour, religion and society. The introduction of a nuclear family with its altered values tends to break the internal ties of the extended family’s values introducing altered behavioural patterns and values with their potential for conflict.

Part of this is caused by the shifting of economic responsibility from a collective to one more dependent on the new economic circumstances of the nuclear parents, particularly if both are earning. There is also evidence in related studies that there may be an effort to inhibit contact between the oldest and youngest members of the family in order to prevent what is perceived to be restrictive or old-fashioned ideas and concepts being passed on – one of the strengths of the extended family.

A complicating factor, and one I have written about in different places, is the influence of servants on children. Increased wealth, lifestyle choice and father and wife working or studying outside the house has enabled or required servants to be brought into the household. This introduces a novel relationship, that between servants and children. It is now common for children to spend more time with servants than with their parents, an insidious influence in the development of traditional familial and social values.

There are a number of factors that govern this. The first is that servants invariably come from abroad, bringing with them their own behavioural patterns, language and a religion which is not always Islam. Their lingua francais often English, and of a standard that is heavily accented and grammatically unsound, a characteristic that leaves children with the advantage of contact with a foreign language at an early age, but the disadvantage of learning it to a poor standard, one that is difficult to change in later life. Their closeness to the children in their charge is reinforced by a natural desire to make themselves indispensable, a behaviour that leads them into spoiling the children in their charge and one that the children learn to manipulate to their own advantage. The introduction of servants and the resulting altered relationship between parents and their children, is a dramatic break with tradition that theoretically weakens the bonds between family members as well as enabling the children of the family to enjoy a more Western lifestyle.

The influence of the differing family relationships is reinforced by the access to Western media and moraes through the media of television, film, music, advertising, travel and the other attractions brought about by wealth and education.

more to be written…

Role of women

The role of women in Islam is being continually discussed and debated within the society, much as it is in the West where, with the increasing numbers and influence of Muslims, the issues relating to Muslim women’s role in both Islam and Western societies form an increasingly open debate. Incidentally, it is interesting to note that, in the West, conversion to Islam is seen by women as being a means of redefining sexuality and enhancing their position within society. I should also add that most debate and criticism in the West is premised on a Western education and received standards that have neither understanding nor tolerance of Islam. While universal suffrage might be a goal for many, the speed at which it is brought about and the damage to established socio-religious beliefs cause significant distress to many.

In the Middle East the consensus of opinion seems to favour the more conservative interpretations of the woman’s role in placing her at the focus of the household, in the pivotal role of wife and mother. This is considered in no way to demean her worth but specifically gives her the critical duty of raising the children and safeguarding the family. In recent years the increasing influences of the West have caused women to look more critically at their position in society and at the influences that have created this situation. Some critics are able to see the root cause of the uncertainties and concerns of Muslim women as specifically emanating from the post-Christian West where women’s changing role is perceived to undermine her focal position in the family. Because of this, and as well as movements within the Islamic society itself, there are a number of countries within which a more public role for women has been actively pursued.

Women in the Islamic world occupy differing positions of achievement in equality with men, much as they do elsewhere but, in general, the West perceives arab women to be in a state of eternal submission. There has been a constant struggle within the various Islamic States to achieve greater parity and, in some cases there has been perceived a real, if slight, improvement in their lot. At the end of the United Nations’ ‘Decade of Women’ in 1985 there was a general feeling that there had been a small amount of progress, but a number of delegates felt that there had, in fact, been regression. Some of the more progressive Islamic States have been able to legislate for, and achieve modest changes in outlook. Egypt, under Nasser, introduced real changes in the early sixties. Challenges from the right wing clergy were fought off but succeeded under Sadat, though today, women in Egypt still enjoy a freedom that is not found in many other States, including the Gulf.

The areas that are considered to be pivotal in determining the role of women in society have been focused on three issues: the

- veiling of the face;

- the public social role of women and their participation in social activities; and the

- activities and social roles of women in the life of Muhammad.

The reasons for focusing on these three issues are essentially that the views of the different schools of thought tend to be reflected in these issues.

Feminist groups have tried to make an impact within a number of States but have really only been successful in struggles where they carried out a supporting role in liberation movements and where, once nationalistic governments were established, their support was not recognised in any real form. Instead feminist groups tend to have been absorbed by various fundamentalist movements and their general thrust dissipated. In the Gulf it was anticipated by many that the massive influx of wealth would enable women to progress at the same time that the States developed their infrastructures. What in fact happened was that a market for Western consumer products was identified and the media – led by Egypt – targeted the Gulf for articles and products that reinforced the role of women as the providers of the home, an idea that brought together issues such as children, food, religious instruction and the upwardly mobile good life. These media have not dealt with issues such as feminism, nor asked unsettling questions about women and their place in the general scheme of things and, apart from a few well-quoted exceptions, women have progressed little towards the Western view of a more equitable partnership with men in the Gulf.

Nevertheless, there has been change and, with increasing education and access to the West both through the media and through travel, it is only the more fundamentalist policies that may be holding back the progress that women’s groups are demanding in the northern Arab States and which, if they were to take hold, would support change in the Gulf. Conflicting with this view it seems that, provided that the men and women of the Gulf can lead a life of increasing comfort, and provided that the opportunities for women to take a more equal role continue to be limited, then it is unlikely that women will fight to obtain the formal settings and necessary legislation they will need to be able to obtain this equality.

Perversely, the position that women have within their households, positions enhanced by the authority of the Holy Quran, gives them considerable strength. It places them where they are able to alter socio-cultural progress by the manner in which they bring up their families, choose wives for their sons, husbands for their daughters and control – to the extent to which they are individually able to do so – their husbands. All this is supported by the increasing education of women with the clear intent of improving their opportunities and bringing more of them into the workforce.

However, they face in fundamentalism, a strong bar to progress. It appears to be a characteristic of women’s position in Muslim society that it is mirrored by the security of Islam. When Islam is secure, then women can be secure and confident within it; when it is threatened, then so are they. It certainly appears to be a characteristic of fundamentalism that one of the external aspects of the society, the appearance of women, is one of the first aspects to be constrained by decree, often in ways that seem harsh to the Western world. Certainly women have attained a different standing in society in different States, but this appears to be threatened when traditional aspects of Islam become an element of religio-political pressure in the society. It is argued that the control of women is a symbol of the power of men and their honour.

A characteristic of this rise is that it is funding, to a large extent, from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait that is responsible for the development of traditionalism or fundamentalism, the sadder aspect of this development being that few Islamic States have given women their full rights, and both Islamic law and the message of Islam are being violated.

Finally it is worth noting that there is not likely to be overall acceptance of an increased women’s role in society other than may be possible in one or two Islamic States. These are unlikely to include any Gulf States though, with the pressures building up since the Gulf War and Iraq intercession within both the Gulf States and Saudi Arabia, this may well change. Qatar, particularly, under the guidance of Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa, seems intent on altering attitudes.

Ibn Khaldun (732/1332-808/1406), an intellectual whose teachings are said to be as valid today as they were in his time, said in his Muqaddima, an early Muslim view of a universal history, that

‘Allah does not give orders directly to a person unless he knows the person is capable of carrying them out. Most religious laws apply to women just as they apply to men. Nevertheless, the message is not directly addressed to them; one resorts to analogy in their case, because they have no power and are under the control of men.’

That women appear to have no power goes to the heart of the Islamic principle that women do not have the same rights as men. In discussing the conditions necessary for being a caliph – the authority who obeys shari’a, divine law – Ibn Khaldun set out four principles that govern the requirements for the role:

- knowledge,

- equity,

- competence, and

- general fitness.

It is particularly in the fulfilling of the third of these that Ibn Khaldun considered that no divine mission could be ascribed to women. In consequence it is only in the fields of intellectual attainment and politics that women have been able to make any impact on an increased role for themselves in an Islamic society. It is unlikely that those who control religious law will be too concerned by intellectual developments – normally the province of individuals in universities – but they are likely to worry about political, popularist initiatives. There is considerable room for debate.

bay’ah is the solemn commitment Muslims make to obey, and it can be argued that it conflicts with universal suffrage. It follows that a Muslim should not participate in elections as, firstly, bay’ah is final and not, like elections, renewable at regular intervals. Secondly, bay’ah is the priviledge of notables; those who have a part in decision making and not the ’ummah – the common people. Conversely, it can also be argued that the fairest way of making bay’ah is for it to be operated through a full and free election.

Health

The subject of health in Qatar is one that could be located on many of these pages, but I have placed it here as it is undoubtedly one of the pressures that must be faced by the population of the peninsula generally, and Qataris in particular. There are health problems to be found in all societies, but those developing in societies that have grown quickly, are subjected to significant internal and external socio-cultural pressures, and where there is high personal income, are difficult to approach and counter with effective treatments.

Drugs and sexually transmitted diseases are common problems for which policing and treatment are available for the former, and identification and treatment for the latter; but it is obesity, so common in many parts of the world that is having a dramatic effect on those living in Qatar, particularly upon Qataris.

The causes of the problem are relatively easy to identify, and relate to a number of factors, among them being the

- considerable wealth of Qataris,

- commercial pressures to change life styles,

- availability of fast foods,

- poor dietary education,

- more complex family timetables,

- the prevalence of expatriate maids and carers,

- competing requirements for time which encourages poor habits, and

- concomitant stress.

One of the benefits of increased economic activity in Qatar has been the greater levels of disposable income enjoyed by Qataris. This has been matched by a variety of socio-cultural and economic pressures that have encouraged local habits to change. A generation ago the local diet was relatively simple and relied to a great extent upon the consumption of rice, fish and dates, particularly by those of the population of badu stock. Meat, because of its value was rarely eaten, except when served to guests and dignitaries.

Nowadays, purchasing power enables locals to buy a wide range of foods both to be cooked in the house as well as being bought from fast food outlets and restaurants for consumption there, in the house or on the move. While this has brought a considerable amount of meats and sugars into the diets that were not there previously, it is a diet that tends to omit fruit and, particularly, vegetables.

Families find themselves more busy, needing to allocate time for schooling and work as well as for the greater range of passive and active recreations available to them and their friends. This requires them to arrange their days around timetables that vary considerably, reducing the ability of families to meet and eat together and encouraging snack eating.

Poor dietary education may be one of the factors relating to healthy eating, but even where there is education, many find the ability to work to a steady programme hard to manage. Traditionally meals tend to be larger than is needed for immediate consumption and, with the pressures created by work and relationships, there is a tendency to crave the immediate apparent benefits of fats and sugars.

In addition to this, the ability to afford expatriate labour has meant that at lot of families employ women from the Indian sub-continent and the Philippines to act as maids and carers for their children. These women rarely have dietary education themselves and may even be unfamiliar with the new cultures in which they now find themselves. This, combined with poor language skills and a desire to keep the children in their care happy and, by extension, their parents, suggests that there is a tendency to cater for children’s whims rather than insist on a considered diet. It is notable that many of the children under ten seen around the shopping malls tend to be in the care of expatriate nannies.

The result of all this is that obesity has increased dramatically in Qatar. A 1989 study concluded that 63.7% of adult females of the age eighteen and above were obese, that is they had a Body Mass Index equal to or over twenty-five, and that percentage is higher than any of the other countries in the Gulf states. While it may be thought that obesity is due to genetic disorders such as Cushing’s syndrome and hypothyroidism, there is a low incidence of these in the region, thus supporting the dietary argument.

An aggravating factor is likely to be the sedentary lifestyles that are rapidly being adopted. Whereas there was considerable hard work and pedestrian movement, modern work and patterns of behaviour around the house have created more sitting and less physical activity. Two other factors are considered important. Firstly, the clothes worn by women tends to mask their own view of their shape, making monitoring difficult and, secondly, not many women actively exercise. A study in 1994 discovered that 56.5% of the women in Qatar did not exercise, 27.5% exercised infrequently, and only 16.5% exercised regularly, but that the majority of these were not Qatari women.

With increasing obesity has come a range of medical problems such as serious chronic diseases including diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases. There is also an increase in dental problems created by the intake of sweet food and drink.

What is particularly surprising is that obesity has been found to be more prevalent in highly educated females at 60.5%, than in those with low education levels. It is suggested that this is likely to be because the former have little time to prepare food and that their work patterns and resulting stress levels encourage them to eat foods high in fats and sugars in order to provide them with the energy they require.

Heritage

Elsewhere in these pages there are notes relating to the loss of buildings and street patterns to the new developments required to bring higher standards for those living in the peninsula. With their loss there has been not only the disappearance of the traditional urban environment but the concomitant socio-cultural living patterns which created them. Now, living in completely changed physical, environmental and socio-cultural patterns, many feel a palpable sense of loss for the traditions and history which that environment represented. Those too young to know those times also feel a sense of historical deprivation when they compare their country with those they visit abroad.

In order to deal with this there have been a number of initiatives designed to encapsulate something of the past. The first of these was the creation of the Qatar National Museum based on the old palace of Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim at feriq al-Salata. Other initiatives have been started, both public and private, relating to music, dance, falconry, boat-building, family life, play and pearling. While this has not yet been fully integrated, the Qatar Museums Authority has an interest in coordinating and directing much of it.

Population balance

The lack of a permanent home for expatriates has given each of the expatriate national groups a high degree of nervousness about their several futures, and encourages greed over commitment. Although it has been intended that Qataris will continue to increase as a proportion of the overall population this is not working out in practice. There is likely to be a continuing need to import labourers as well as some middle management for necessary work, and it will be necessary for the State to deal with the issues of dependency this produces both personally and institutionally. In addition there is the continuing need to find responsible roles in the world – Arab, Muslim and international – as well assist in settling the problems relating to Palestinians within the overall Arab and Muslim world.

So, on the one hand there is a national population that has political and administration systems and Western moraes in conflict with its traditional Islamic values and, on the other hand, a massive transient population upon whom Qataris are increasingly dependent and who, by their nature are a highly visible reminder of the way in which Qatar operates.

The same problem exists, to a greater extent, in Dubai where it is becoming increasingly criticised from both within and outside the country. The counter argument that is made there is that this is a very valuable resource, enabling on a micro-economic scale, benefits to be made to the countries from which the expatriates come.

There is more written about these and related issues on the population page.

Language

Arabic is not an easy language to learn or master, particularly for a European as its script and grammatical structure are radically different from European language forms and, most importantly, it is intrinsically bound up with the Holy Quran. Many of the foreigners who come to Qatar do not speak Arabic and, because of this, English has developed as a second common language due to its prevalence among the nationalities who come to the country.

To some extent this has stopped foreigners learning Arabic although many learn enough as is necessary for their work or for living in Qatar. It is understandable that the Arabic language they learn to speak is simpler than Gulf Arabic, and that the Qataris speak a simplified version of Gulf Arabic to those foreigners who converse with them. Despite this it is possible to carry out work in Qatar without having to know Arabic, particularly in technical areas where English generally is the medium of communication because of the extent to which technical terms are used.

But there is the beginning of resentment against those who do not know or, particularly, do not wish to learn the language. Qataris are right to feel that foreigners should make an attempt to speak their language and that business should generally be carried out in the medium of Arabic, but the reasons given by critics are interesting in that they generally include the argument that it will encourage foreigners to mix with Qatari society. Here there is a distinct contradiction between a stated desire to soften the barriers between national and expatriate societies, and the State’s general policies – such as short term residency, no ownership of land by foreigners, housing and rental policies and, of course, the cultural and religious backgrounds – that do little to assist this.

There is also the conflict I have heard stated between admiration for those with a good command of Arabic and the concern that much may be learned by such foreigners of the private operation of society.

Education

It is evident that education is going to be a major area of focus for the State. The rapid development which has been embarked upon is drawing attention to Qatar’s changing and developing relationships in the Gulf, the Arab region and the wider world. This is creating pressures on both the nationals and expatriates living within it as well as those having interests there. The wider Arab world will also be affected by educational development in Qatar, directly and indirectly.

Sheikha Mosa, the mother of the Ruler, has been influential in bringing forward not only the education of women but the profile of education within the Gulf, and this in itself is having an effect on the traditional socio-cultural moraes of the society. In particular, the introduction of Western educational establishments and their academic staff and students will have a profound effect on the process, regardless of the pedagogical and educational processes involved. While there is an irony in introducing foreign universities and their staff to develop and improve national educational performance, it is also the physical introduction of these institutions and staff which is likely to have effects that will be difficult to control both within the country as well as in the wider Arab region, particularly the poorer Arab States.

The educational system is directed by the Supreme Education Council. The system employs a large number of Arabs from other countries, giving free education to all who wish. For those who want it there is also adult education. The education of the two sexes is strictly segregated at all levels of schooling, and all education is free to nationals, including the children of expatriates who work in the public sector.

Primary schooling is broken into two stages:

- preparatory – 6 years, and

- elementary – 3 years;

This is followed by:

- secondary – 3 years.

The six years preparatory schooling is compulsory.

There are also a range of facilities dealing with special subjects. This includes:

- private education,

- literacy and adult education,

- special needs,

- scientific secondary schools,

- a language institute, and a

- department of training and vocational development.

In addition there are educational facilities for expatriates at a range of:

- private schools at both primary and secondary levels, and

- a number of kindergartens for both national and expatriate children.

The Supreme Education Council directs three institutes designed to carry forward education initiatives in the State:

- the Education Institute which oversees and supports independent schools,

- the Evaluation Institute that monitors and evaluates both schools and students, and the

- Higher Education Institute which advises students on higher education both in Qatar and abroad, and administers grants and scholarships.

At tertiary level there is some technical training available, but the emphasis is on taking students through a university education. In the early seventies, and with the rapidly increasing oil prices, the State began to investigate the possibility of establishing a University. There were arguments that this might be better dealt with

- by training the students at existing Universities elsewhere as this would be more cost effective for the relatively small numbers of students requiring it;

- it would give Qatari students the ability to learn at well established Colleges selected throughout the world for their ability to match teaching to need; and

- that Qatar should concentrate on technological education that was obviously more needed by the evolving requirements of the State.

Qatar Foundation for Education, Science and Community Development was established in 1996 and has grown to encompass a number of facilities for students from the age of three upwards. Its aim is to benefit and and develop the state through initiatives in education, science and research. Under its aegis Education City has been established to the west of Doha comprising a number of foreign branch university campuses, listed below. The intent is to provide an integrated educational environment to encourage synergy and interaction between existing educational and recreational facilities on the site and those envisaged within the new academic and medical areas of the University.

Perhaps more importantly, there is a significant attempt to broaden the base upon which education in the peninsula has been established. In this Qatar has established links with a number of external universities. These now number some eighty educational, research, science and community development organisations.

The reason behind the establishing of Education City is interesting and illustrates the thinking driving much of the initiatives under way in the peninsula. There is an understanding that change is rapid and that, for Qataris to benefit both within the peninsula as well as abroad, there must be a cross-fertilisation of ideas. The establishing of foreign campuses on the Education City site anticipates the benefits this might bring to their students, benefits that are reinforced by the student population being relatively small by international standards. The campuses now comprise:

- Texas A & M – TAMUQ,

- Virginia Commonwealth – VCUQ

- Georgetown – SFS-Qatar,

- Carnegie Mellon – CMU-Q

- Weill Cornell Medical College – WCMC-Q,

- Northwestern University in Qatar – NU-Q,

- CHN – now known as Stenden after its merger with Drenthe University,

- École des Hautes Études Commerciales de Paris – HEC Paris, and

- University College London.

All of the above are from the United States except Stenden which is from the Netherlands, HEC, the French business school, and UCL from the United Kingdom which will focus on conservation, museum studies and archaeology.

In addition to the above there is also a Qatar University based in Education City:

- Qatar Faculty of Islamic Studies – QFIS,

as well as three educational centres based in Education City:

- Qatar Academy, the

- Learning Centre, and the

- Academic Bridge Programme.

In addition to the above educational campuses, there are a number of other centres based in Education City. Three of them are based on research and industry:

- Rand-Qatar Policy Institute – RQPI,

- Qatar Science and Technology Park – QSTP, and the