a collection of notes on areas of personal interest

The battle of Vittorio Veneto, northern Italy – Autumn 1918

This note was begun only with the purpose of identifying the area in which one of my relations was killed in the Great War. It is not intended to be a description of the war in Italy.

Yet it should be noted that this was one of the more forgotten, or disregarded theatres of the Great War, the north of Italy being the setting for confrontation mainly between Austro-Hungarian troops and those of Italy, Great Britain and France. Other nations were certainly involved, Germany reinforcing Austro-Hungarian initiatives, while British and French colonies, along with the United States provided equipment and personnel to the Allies.

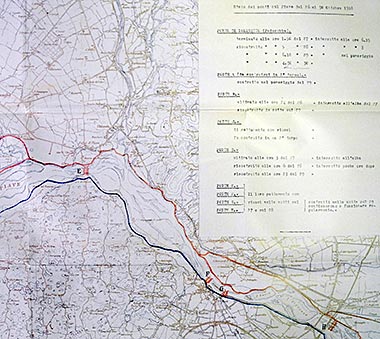

The town of Vittorio Veneto came into being on the 27th September 1866 when, under the reign of Vittorio Emanuele II, the two old towns of Ceneda and Serravalle, set in the foothills of the Alps in the Veneto, north of Venice, Italy, decided to unite under the name of Vittorio. The name of Vittorio Veneto is now linked as a setting for one of the closing actions of the Great War, the above map identifying the general location.

After the Italians joined the Allies in 1915 their army, augmented by British and French troops, faced the Austro-Hungarian empire in northern Italy.

Field Marshall Count Luigi Cadorna, the son of General Raffaele Cadorna – who led the Risorgimento and took Rome in 1870 – reorganised the Italian army prior to the First World War and led the fighting in north Italy under King Vittorio Emmanuel III, the nominal Commander-in-Chief.

With the collapse of the Russian front and the peace treaty signed in March 1918, the Axis forces were able to release more troops. Ludendorf, facing considerable difficulties on the Western Front against the Allies needed relief and hoped this might be accomplished by a counter-attack. At his insistence the Austrian-Hungarian alliance decided to move against northern Italy in a pincer movement, attacking Asiago in the north and Piave in the east.

Ferdinand Foch had been appointed Chief of the General Staff and then Supreme Allied Commander in March 1918 following intense lobbying by Georges Clemenceau, the French Prime Minister.

At this stage, not only were the Austrians being pressured by the allies in Italy, they were unable to obtain relief from Germany due to the problems they were facing on the Western Front with the success of the allied initiatives there.

Meanwhile, in Italy, Field Marshal Cadorna was relieved of his duties and his place taken by Field Marshal Armando Diaz who appeared to be unwilling to mount a major campaign despite the success of the allies in June. However, minor operations continued to apply pressure against the Austrians. Plans were put in hand at the insistence of Foch and General Frederick Lambart, 10th Earl of Cavan, Commander-in-Chief of the British forces in Italy, to attack the Austrians on the river Piave with the purpose of advancing to Vittorio Veneto and splitting the Austrian line between those on the plain and those in the mountains, exposing the latter to the threat of being rolled up from the south.

more to be written…

Asiago

The Austro-Hungarians were able to provide fifty-two divisions to face the allies. Facing them the Italians had four armies: the Third, Eighth, Tenth and Twelth comprising fifty-seven divisions which included three British – the 7th (which had seen action at Bullecourt), 23rd and 48th – as well as two French and a Czechoslovakian division, and an American infantry regiment.

In June, the opposing forces were relatively evenly balanced and the fighting confused. The Austrian attack initially made some ground but the allied counter-attack regained that and more, the Austrians suffering well over 50,000 casualties, the majority of them at Asiago.

Their confidence sapped by a combination of losses and German requests for help on the Western Front, Austria joined Germany in their request to President Wilson for an armistice in the beginning of October 1918.

In the meantime Field Marshal Diaz had reorganised the allies into two armies: the Tenth under the command of General Cavan, and the Twelfth under General Graziani. By the beginning of October the allies now had sixty divisions facing sixty-one Austro-Hungarian divisions, though the latter enjoyed a considerable superiority in guns.

more to be written…

Piave

The river Piave flows in a roughly south-easterly direction across the Adriatic plain from the Alps in the north to the Adriatic sea east of Venice. It is broad in places with its character changing with the seasons. It contains a number of islands, the largest of them being Papadopoli, about four miles long.

In the evening of the 23rd October 1918, the Allied armies attacked across the island. For their part, the 22nd Brigade of the 7th Division, which included the 2/1st Battalion of the Honourable Artillery Company – and Lance Corporal Harry Cassini – began the process of crossing the river in twelve flat-bottomed boats or barges under the control of skilled Venetians.

The defence by the Austro-Hungarian troops was not that spirited, no boats were hit and the platoons landed with few casualties. Regrettably, one of those was my granduncle, Harry Cassini, his best friend, my grandfather and also with the Honourable Artillery Company, having been killed previously at Bullecourt in northern France.

The map above illustrates the positions for the temporary bridges set up or planned on the 26th to the 30th October 1918 for the crossing of the river Piave.

The allied presence on the island was consolidated and, four days later, the British attacked the defensive bund on the east bank of the river and took it immediately, by the end of the day advancing three kilometres to the east away from the river.

The next day the British expanded their three bridgeheads and the allies advanced to the river Monticano which, despite strong opposition, they crossed driving the Austrians before them, but finding themselves tired, running out of supplies and moving too far ahead of the Italians on their flank.

Nevertheless, the allied advance continued apace despite the above problems, the Eighth army taking Vittorio Veneto on the 30th October and the Third and Tenth armies driving on to the river Livenza but stopping on the 31st October to await supplies, and in order not to make the mistakes the Austro-Hungarian troops had with extended supply lines. This photograph, taken following the battle of the Piave river, shows King Victor Emmanuel III visiting his troops and watching as General Diaz awards a medal to a Sergeant in the elite Arditi troops.

more to be written…

Vittorio Veneto

The advance was continued on the 1st November and the river Tagliamento was crossed but, on the 3rd November 1918 at 3.20pm, a general armistice was signed at Villa Giusti at Mandria, outside Padua, and the advance halted.

A week later, at 11.00 am. on the 11th November 1918, the Germans signed the armistice at Compiègne in northern France, which formally brought to an end the war in Europe.

more to be written…